Bartok Violin Concertos

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

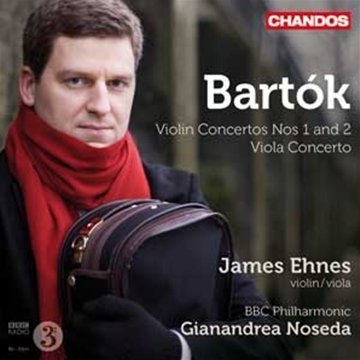

Composer or Director: Béla Bartók

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Chandos

Magazine Review Date: 11/11

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 77

Mastering:

Stereo

DDD

Catalogue Number: CHAN10690

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 1 |

Béla Bartók, Composer

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Béla Bartók, Composer Gianandrea Noseda, Conductor James Ehnes, Violin |

| Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 |

Béla Bartók, Composer

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Béla Bartók, Composer Gianandrea Noseda, Conductor James Ehnes, Violin |

| Concerto for Viola and Orchestra |

Béla Bartók, Composer

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Béla Bartók, Composer Gianandrea Noseda, Conductor James Ehnes, Viola |

Author: Rob Cowan

Among the many ‘if only…’ fantasies that marry a particular work to a particular artist is Jascha Heifetz performing Bartók’s First Violin Concerto. OK, granted the work only came to light when its prompting inspiration Stefi Geyer died, but still, 1958 (the year of the eventual premiere) witnessed the height of Heifetz’s prime and if he had had a mind to play it, he easily could have done. I write all of this because, with the possible exception of Isaac Stern (Ormandy and the Philadelphia on Sony – nla), James Ehnes offers us the most ‘Heifetzian’ recording yet, a vibrant, tender-hearted, boisterously youthful account, bittersweet where needs be and eagerly supported by the BBC Philharmonic under Gianandrea Noseda, who are consistently on the ball. The alternation of serenity (first movement, later the First Portrait) and dizzying, up-tempo mood-swings (second movement) has rarely been more securely focused. I can’t think of a finer CD version of the First Concerto than this, though Thomas Zehetmair and Arabella Steinbacher run Ehnes pretty close.

Bartók never thought well enough of his First Concerto to acknowledge his 1938 Violin Concerto as his ‘Second’ and, yes, there’s little doubt as to which work is the true masterpiece. Again, Ehnes and Noseda deliver a spontaneous, keen-edged reading, agile and light on its feet but facing some stiff CD competition. The most recent contender, by Barnabás Kelemen and the Hungarian National Philharmonic under Zoltán Kocsis, was recorded just a few months before the recording under review but sounds as if it hails from a different era, especially in terms of its close-set, ‘in-your-face’ engineering (very ‘Mercury Living Stereo’). Kelemen and Kocsis make a formidable partnership and, to be truthful, their thrilling performance would be difficult to beat. Other viable digital contenders include a coltish Zehetmair in Budapest with Iván Fischer, and Steinbacher, whose persuasive, more relaxed account with the Suisse Romande Orchestra under Marek Janowski benefits from orchestral support that is truly three-dimensional, even if you’re not listening via a super-audio facility. Both versions are coupled with the First Concerto, referred to above. A good place to draw comparisons is the tranquil episode at 2'45" into the first movement of the Second Concerto (marked calmo) where the soloist sings quietly above a shimmering accompaniment of violas, cellos and basses, answered by ethereal upper strings, then woodwinds and horns, before the argument suddenly slams top-gear to forte and is abruptly off for the chase. Ehnes and Noseda judge this passage extremely well, the soloist sweet-toned but keeping just enough emotion in reserve. On Fischer’s disc (2'42"), although the Budapesters sound admirably mysterious in the quieter music, Zehetmair is more matter-of-fact and the forte onslaught is less shocking. Steinbacher (2'45") sounds the most affectionate of the four, Janowski usefully stressing the accompaniment’s rhythmic aspect, while Kelemen (2'43") plays with admirable purity of tone and Kocsis and his orchestra offer a rude awakening with the most violent forte of all! The one tiny point about the Chandos production that bothered me was the vaguely focused string passage that underpins the soloist’s agitated sul ponticello at around 6'54" into the first movement. Beam up Steinbacher and Janowski in the same spot (7'30") and you’ll soon hear what I mean. It’s a very minor glitch but if you know the score well it’ll momentarily pull you up. In general, though, Chandos offers a beautifully balanced sound picture, especially effective in the delicate traceries of the Andante tranquillo second movement, which alternates serenity and playfulness as only Bartók could. As to the finale, never before had I been so vividly reminded of an orchestral masterpiece from a few years earlier, Ravel’s La valse (1920). Bartók’s reworkings of key ideas from his own first movement are, after all, often cast in 3/4 time, and the combination of gaiety and impending catastrophe (which was prophetic in itself, given that this was the late 1930s) does indeed recall the accumulating tensions of Ravel’s masterpiece, although Bartók contrives a rather happier ending.

In the unfinished Viola Concerto, which is in effect the work of a sick man bravely straining to employ a handful of dying creative embers, Ehnes fully matches the excellent Lawrence Power. Indeed, his rich, yielding tone makes an even stronger impression, reminiscent of William Primrose in his prime – which, paradoxically, would have been before Primrose commissioned the work. The kernel of the piece is its slow movement and I challenge any reader to name a version that is either more moving or more beautifully played. I should also mention that Noseda and his players do a superb job with Tibor Serly’s sparse but mesmerising completion of the orchestral score which, in its occasionally alarming textural juxtapositions, reminded me, from time to time, of two other striking ‘late’ works, both of them masterpieces: Mahler’s Tenth and Shostakovich’s Fifteenth. Though not exactly a comfortable listen, Bartók’s Viola Concerto haunts the memory and because of its pared-to-the-bone textures means that Ehnes’s soul-warming contribution comes across as especially powerful. So, an unqualified rave for the First Violin and Viola Concertos, and an enthusiastic endorsement for Ehnes’s version of the 1938 Concerto, even bearing in mind that the listed options offer such exceptional competition. Paul Griffiths provides readable and authoritative booklet-notes.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.