Review - 'Vienna: From Mozart to Schoenberg' (London Sinfonietta / David Atherton)

Richard Whitehouse

Friday, March 21, 2025

Richard Whitehouse on a collection taking in the London Sinfonietta’s 1970s recordings

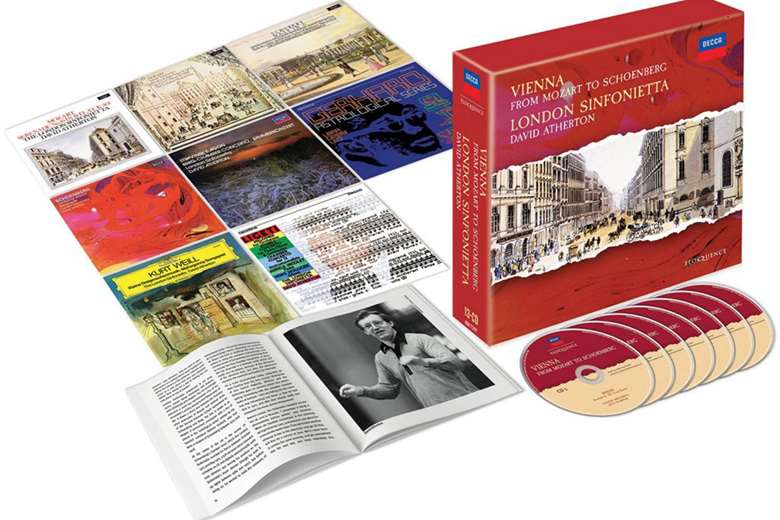

Autumn 1973 saw the London Sinfonietta give a comprehensive overview of chamber music by Schoenberg and Gerhard. It also recorded most of those works by the former, this Decca set comprising the basis of an Eloquence collection that includes almost all the recordings made by the Sinfonietta with its founder-conductor David Atherton during the remainder of that decade.

Writing in August 1974, Jeremy Noble admitted reservations about the sound but praised the conviction of the Schoenberg set overall. That the ensemble works are conducted can lead to loss of spontaneity – as in a lucidly rendered yet emotionally temperate account of Verklärte Nacht, or a First Chamber Symphony which has enviable clarity but can seem expressively unyielding. Pierrot lunaire finds Mary Thomas ideally equating song with recitation, yet her earlier account (Unicorn, 9/74) renders the melodrama’s emotional extremes even more viscerally.

The highlights are those 1920s pieces where Schoenberg gradually elaborates the potential in his serial method of composition. Others might have found more humour in the Serenade but not greater suavity or finesse – witness John Shirley-Quirk in its Petrarch setting – while the Wind Quintet remains unsurpassed for the lucidity brought to its (self-?) consciously applied Classicism, and the Suite-Septet has no lack of elegance or insouciance to offset its acerbity. The last of the Op 27 Choruses has a winning textural translucency, while that of the Op 28 Satires is witty if never didactic. Gerald English is an understated reciter in the scabrous Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte (Kenneth Griffith on DG is still unequalled here), and while violinist Nona Liddell eschews the ultimate angst in the late Phantasy, its cohesion cannot be gainsaid.

Another attraction of the Schoenberg set was its including shorter pieces then little known or unrecorded. Hence the sombrely evocative Ein Stelldichein, the ethereal Herzgewächse with June Barton’s stratospheric soprano, or the distilled Expressionism of the aphoristic Three Pieces. Anna Reynolds brings warm compassion to ‘Lied der Waldtaube’ (from Gurrelieder), while the sardonic cabaret song ‘Nachtwandler’, uproarious march Der eiserne Brigade and ingratiating Weihnachtsmusik convey this composer in an informal light as appealing as it is unexpected.

Only the Astrological Series of Gerhard made it into the studio, these late pieces encapsulating the vital persona of one already falling from favour. Nona Liddell and John Constable suffuse the disjunct sections of Gemini with audibly cumulative inevitability, while Atherton draws a consummate response from the Sinfonietta in the tensile sextet Libra and its more discursive yet equally powerful companion Leo (respective star signs of the composer and his wife) that both conclude in affecting intimacy. This excellent release is only now reissued, whereas that of Ligeti has rightly always been available, as its Chamber Concerto and Melodien are among the finest in their melding stark contrasts with quizzical humour; but not even Aurèle Nicolet and Heinz Holliger can make the Double Concerto sound other than a retread of earlier ideas.

This 1975 album came hard on the heels of the Sinfonietta’s major Weill retrospective, crucial in rehabilitating one who had been labelled a left-field songster. Lithe and incisive, Atherton’s Kleine Dreigroschenmusik sets the tone for a survey where Nona Liddell makes a persuasive case for the deftly sardonic Violin Concerto, as does bass Michael Rippon for the implacable fatalism of Vom Tod im Wald. A formidable line-up of British singers ensures the provocative Mahagonny-Songspiel is much more than ‘Alabama Song’, while the revue-like Happy End has memorable numbers other than its inimitable ‘Surabaya Johnny’. The ‘First Pantomime’ from the early Der Protagonist sounds unintentionally hilarious, but Das Berliner Requiem still packs a considerable punch through its unremitting starkness and emotional plangency.

Little of 1978‑79’s Webern/Schubert series appeared commercially, save the latter’s Fourth Mass graced by contributions from Phyllis Bryn-Julson and Jan DeGaetani, two early works for wind ensemble and a suitably fervent account of his masterly final setting of ‘Gesang der Geister über den Wassern’. Also set down were Mozart’s last three wind serenades: Atherton presides over that in B flat, most perceptive in its two Menuettos and Theme with Variations, whereas clarinettist Antony Pay directs those in E flat and C minor – the former as genial as the latter is impulsive. Pay comes into his own in Spohr’s First and Second Concertos, their eliding Classical elegance with Romantic flights of fancy enticingly realised by one then at the forefront of ‘authentic’ practice. A 1980 release couples Berg’s Chamber Concerto, any intractability more than offset by characterful contributions from violinist György Pauk and Paul Crossley, with Stravinsky’s ballet Agon, which duly emerges in all its colourful abstraction.

At the start of his booklet interview with Atherton, Peter Quantrill notes how Schoenberg’s portrait ‘stares defiantly back at those few who care to find it, perennially returning their gaze with interest’: a challenge these Sinfonietta recordings capture in abundance.

The recordings

Vienna – From Mozart to Schoenberg

London Sinfonietta / David Atherton (Eloquence)