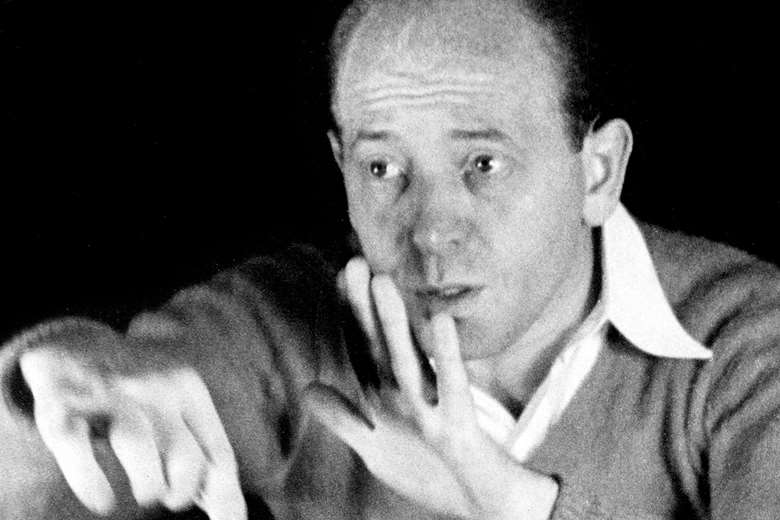

Review - Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy: The Columbia Stereo Recordings 1964-1983

Jed Distler

Friday, March 21, 2025

Jed Distler delves into a massive collection focusing on the conductor’s later discography

This second of two mammoth box‑sets devoted to Eugene Ormandy’s complete stereo Columbia Masterworks output covers recordings released between 1964 and 1983. It encompasses 94 newly remastered CDs packaged in original-jacket facsimiles and organised chronologically by their initial release date. An accompanying 223-page hardcover book contains complete session data and a discography by composer. As with the previous box, Gramophone’s Rob Cowan provides a booklet essay that probes the salient traits of Ormandy’s music-making and the sheer range of repertoire he led during his Philadelphia tenure.

In William Barry Furlong’s book Season with Solti (Collier Macmillan: 1974), Sir Georg cited the Philadelphia Orchestra under Ormandy as the only American orchestra that he would rank with his own Chicago Symphony as being well balanced in all sections and better balanced than their Vienna and Berlin counterparts. Ormandy attributed the full-bodied richness of the Philadelphia string section to his own experience as a violinist, in contrast to the sharper, more percussive beat of conductors who were pianists. Indeed, when George Szell recorded Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with his Cleveland Orchestra, the piano soloist Leon Fleisher recalled how, when it came time for the 18th variation’s famous big tune, Szell apparently mouthed to his players ‘like the Philadelphia Orchestra!’, in order to evoke Ormandy’s predilection for lush string textures.

Many American collectors trusted Eugene Ormandy first and foremost, and for good reason

In my review of the first box (12/23), I discussed how Ormandy’s Tchaikovsky most readily reveals the conductor’s quintessential traits. It represents a plush, almost epic interpretative style that we’re not likely to encounter any more, in stark contrast to modern-day conductors who favour light textures, rigid rhythms and emotional coolness. Granted, the Fourth Symphony’s broadly paced finale may not match the surface excitement or drive heard in contemporaneous traversals by Mravinsky, Dorati and Markevitch. Yet in the first-movement development section’s climax, notice how the Philadelphia strings lean into the principal theme with an intensity and fervency that leaves even the seamlessly impeccable Karajan/Berlin and Haitink/Concertgebouw string sections behind. Ormandy’s disc of excerpts from the Nutcracker ballet goes beyond the Suite to include a good deal of additional music. It’s easy to hear why it was a best seller, not just for the strings but also for the March’s impactful percussion and the Divertissement’s deliciously characterised woodwind-playing.

When it came to orchestral showpieces, ranging from overtures to tone poems and from Russian Romantics to French Impressionists and beyond, many American collectors trusted Ormandy first and foremost, and for good reason. ‘You simply can’t find a better-played and better-conducted recording than this one’, wrote my colleague David Hurwitz on the stereo Mussorgsky/Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition, and he’s right. Every movement features each orchestral section and first-desk soloist on their top game. The Limoges Marketplace bustles without freneticism, the Unhatched Chicks cackle with fresh wonder, the Old Castle’s saxophone soloist oozes sex minus vulgarity, while the brass, chimes and tam-tam collectively transform Kyiv’s Great Gate into a heavenly entranceway.

Ormandy’s Strauss will appeal to those seeking the aural equivalent of Technicolor, and just enough creamy sensuality in lyrical passages to go over one’s daily calorie count. But there’s more musical substance than meets the ear. In the 1963 Also sprach Zarathustra, you’ll rarely hear the final Dance Song (Tanzlied) and the culminating midnight bell sustain comparable climactic momentum elsewhere, except in Ormandy’s RCA and EMI remakes. Le bourgeois gentilhomme is quite lively and ingeniously balanced: sample, for instance, the sophisticated interaction and rhythmic spring between soloists and ensemble in the fourth movement. The Rosenkavalier Suite gets a square start but gains shape and flexibility en route. Ormandy paces the Dance of the Seven Veils cannily: he holds back at the beginning, allowing the syncopated accents to lock in, and scales the dynamics so that the climaxes reach specific plateaus before the final devastating onslaught. Though impeccably groomed, a 1963 Till Eulenspiegel lacks the ribald humour and sharply profiled linear interplay of Kempe/Berlin or Szell/Cleveland.

The disc ‘Wagner Favorites for Orchestra’ matches its Vol 1 predecessor, ‘The Glorious Sound of Wagner’, in every way. If any conductor could fuse Toscanini’s stringency and Stokowski’s opulence, it was Ormandy. He lets rip in the Lohengrin Act 3 Prelude without sacrificing one iota of rhythmic definition and sectional balances in the rapid triplet accompaniment, while the Tannhäuser Overture in standard form excites no less than the expanded Venusberg option in the 1958‑63 box.

Unlike conductors who tend to play early Stravinsky in the style of later Stravinsky, Ormandy revels in the Petrushka Suite’s opulent instrumentation, yet without glossing over intricate details. Listen to how the rapid solo woodwind licks, percussion rejoinders, swirling piano runs and string ostinatos interact within a sophisticatedly balanced perspective in the Russian Dance, and you’ll agree. Less surprisingly, Ormandy’s Rachmaninov’s First and Third Symphonies alternately gush and sizzle. His Columbia Shostakovich Fifth Symphony doesn’t match the edgy commitment of the 1975 RCA Victor remake’s outer movements, but the Tenth remains a marvel of judicious pacing and jaw-dropping virtuosity; just why this recording never got its due remains a mystery. But Ormandy’s Prokofiev Classical Symphony, Lieutenant Kijé Suite and The Love for Three Oranges Suite remain points of reference on every level, where the spotlit sonics say ‘if you’ve got it, flaunt it!’

If Respighi’s Gli uccelli and Vetrate di chiesa lack the last word in lightness and transparency, Ormandy’s 1968 remakes of the composer’s Pines and Fountains of Rome suites supersede his earlier Columbia stereo efforts. Kodály’s Concerto for Orchestra, Dances of Galánta, Dances of Marosszék and Háry János Suite also showcase the Philadelphia musicians in their most flatteringly idiomatic light. The brawn and power in the outer movements of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, however, miss the sinewy angularity served up in the Ančerl/Czech Philharmonic and Kubelík/Boston Symphony recordings, and, for that matter, Ormandy’s 1954 mono version.

In my March 1999 Ormandy Reputations article, I wrote how Rudolf Serkin told Emanuel Ax that Ormandy was the only conductor he’d trust without a rehearsal. Yet the numerous concerto collaborations in this collection prove that Ormandy is an active partner, as opposed to a mere time-beater. Since most of these frequently reviewed concerto recordings have appeared in box-sets devoted to their respective soloists, I’ll defer further commentary. That said, I welcome Gold and Fizdale’s bracing Mendelssohn two-piano concertos back to the catalogue, as well as the young Ivan Davis channelling Horowitz in Liszt’s Hungarian Fantasy. We can also skip over such dross as the holiday, religious and patriotic-themed albums with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, but they’re here if you want them.

Many collectors of my generation first learned Nielsen’s First and Sixth Symphonies from Ormandy’s recordings, not to mention his still-great Ives First Symphony and First Orchestral Set traversals. The world-premiere Mahler Tenth in Deryck Cooke’s first version still holds its own, as does Das Lied von der Erde with Richard Lewis (slightly less fresh than in his Reiner/Chicago version) and Lili Chookasian. Ignore Ormandy’s pungent Bruckner Fourth (what uncommon clarity and lilt he elicits from the woodwinds and antiphonal brass) and Fifth at your own loss. A sumptuously idiomatic Gerswhin An American in Paris features the best-integrated and most musical-sounding car horns on disc. And where has Ormandy’s intensely expressive Schubert Fourth been all my life, with the Scherzo’s cross-rhythms perfectly accented over the bar lines? We get the remainder of Ormandy’s warmly authoritative Brahms symphony cycle (Nos 2, 3 and 4), and a terrific Dvořák New World, where Ormandy gets the London Symphony Orchestra to sound positively Philadelphian.

Alec Robertson made nitpicking yet fair-minded comparisons between the Giulini and Ormandy Verdi Requiem recordings (7/65). Rehearing both, I now lean towards Ormandy for the vividly captured orchestral image and more consistently matched vocal soloists. Similarly, the Berlioz Requiem must have been a sonic revelation for its time in regard to dynamic range and the careful deployment of the myriad brass ensembles and powerful timpani. However, the Temple University Choir are less adroitly balanced in comparison with their New England Conservatory counterparts in the classic Munch/Boston recording. But don’t dismiss Ormandy’s fervent, emotionally generous and utterly alive Easter Oratorio and St John Passion recordings as ‘Bach‑maninov’!

Granted, the Beethoven Missa solemnis occupies a few rungs below the transcendent Klemperer/Philharmonia, Bernstein/Concertgebouw or live Szell/Cleveland versions, but Ormandy’s strong advocacy for the composer’s uneven though fascinating Christus am Ölberge was justly noted in Alec Robertson’s perceptive review (3/70). In Ormandy’s Beethoven symphonies, you’ll notice the Toscanini influence in No 6’s earth-rattling storm, No 7’s songful quasi andante treatment of the Allegretto, No 8’s stringent Menuetto, No 1’s hard-hitting humour in the outer movements, plus the unswerving momentum throughout No 9’s first movement and the Scherzo’s double repeat observed. While Szell, Dohnányi or Mackerras offer more chamber-like textural scrutiny, Ormandy’s interpretative and instrumental proclivities add up to one of the catalogue’s most undervalued Beethoven cycles.

Reflecting upon the magnitude and scope of the Ormandy box-sets, as well as the professionalism, dependability and consistency characterising his unprecedented 44-year Philadelphia music directorship, I can understand why it was easy to take Ormandy’s ubiquity for granted: after all, such qualities do not a cult figure make. Yet, as I hope I’ve made clear, the evidence speaks for itself. Will Sony/BMG lavish comparable loving care upon the complete Ormandy RCA Victor Philadelphia recordings?

The recordings

The Columbia Stereo Recordings 1964-1983

Philadelphia Orchestra / Eugene Ormandy (Sony Classical)