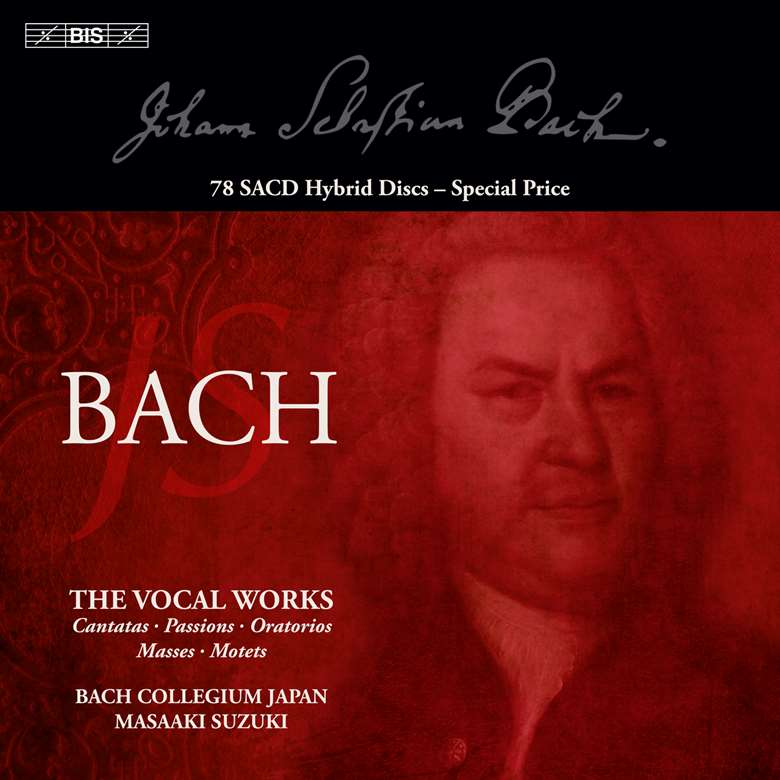

Review - JS Bach: The Complete Vocal Works (Bach Collegium Japan / Masaaki Suzuki)

Jonathan Freeman-Attwood

Friday, June 14, 2024

Jonathan Freeman-Attwood assesses Masaaki Suzuki’s cycle of Bach’s vocal works

Unlike others who have made complete recordings of Bach choral music, Masaaki Suzuki and Bach Collegium Japan didn’t ease their way in for their first major recording with Baroque miscellany but audaciously launched into the composer’s first masterpiece, Christ lag in Todesbanden (Cantata No 4). That initial volume from 1995 was the beginning of a leisurely expedition over 23 years, a traversal of all Bach’s cantatas, Passions, Masses and oratorios. It is now presented in its entirety for the first time in an easily navigable journey of colour-coded periods: the first works from Arnstadt, Mühlhausen and Weimar (rust), the audition pieces for Leipzig and the first cycle from his first year (yellow), the chorale cantata cycle (light green), dark and light shades of blue for the remaining surviving cantatas, secular cantatas (orange) and dark green for the Passions, Masses and oratorios – all with listings, texts and notes presented in four handsome booklets.

If the finest projects are built on traceable teamwork, they must start with a vision, singularity of purpose and a good dose of unbridled instinct. BIS’s boss, Robert von Bahr, saw how the vital ingredients of Masaaki Suzuki’s artistic ambition would ultimately define his label’s crowning achievement. At its heart was Suzuki’s uncanny ability to root his aesthetic in the capabilities of his Japanese musicians while drawing on his own European tutelage. As the series unfolded with greater global reach, so more European and American singers joined the throng. The orchestra and choir of Bach Collegium Japan have, however, remained almost entirely Japanese. The evolution of members (especially the obbligato instrumentalists) has been akin to watching a family grow – and in Suzuki’s case, literally, as his wife, brother and children have all played important roles at various stages of the journey.

Some cantatas are so persuasively distilled and crafted that they become imprinted on one’s memory

Once the die was cast in that first volume, the immediate response was perhaps predictable. One interviewer described Suzuki’s first release as if ‘a man from Mars had arrived’, such was the reaction to a group of Japanese musicians engaging in the heartlands of Bach’s musical and liturgical world. Suzuki recalls that he was quite surprised: he simply ‘wanted to keep performing Bach cantatas’, while quietly reminding people that Bach performance had been long-established in Japan. More telling still, he made clear that ‘the God in whose service Bach laboured and the God whom I worship are one and the same’. Reflexive cultural shock was thankfully short-lived. The steady stream of releases soon confirmed that these were performances that both rivalled and complemented the parallel Erato series from Ton Koopman (Suzuki’s teacher), the pioneering edition co-directed by Gustav Leonhardt and Nikolaus Harnoncourt (which had finished five years earlier) and John Eliot Gardiner’s first recorded forays for Deutsche Grammophon, a series soon to modulate into the fruits of the millennial ‘Pilgrimage’, captured on his own label Soli Deo Gloria.

Suzuki nevertheless acknowledged that his personal foothills were the hard yards of preparation before the cycle began. It started with the inherent nature of the Japanese language which, unlike European languages, does not separate vowels and consonants. The ensemble soon found solutions, not just by imitating Germans but seeking a world of pronunciation that was aligned closely with instrumental practice and approach to sound, contributing to a luminous articulation and timbre, as well as an expressive focus that matured significantly over the years – and all helped by the effervescent acoustic of the Shoin Women’s University Chapel in Kobe. In terms of forces, Suzuki, like Koopman and Gardiner, employed a flexible choral force of around five or six voices per line. Like many current practitioners of Bach’s cantatas, oratorios and Masses, he has always been driven by pragmatic choices that lead to the most satisfying musical results. As Suzuki commented in his Gramophone interview with Lindsay Kemp (12/13), he does not commit himself to the one-to-a-part argument, even if he has occasionally chosen to apply single-voice choruses in concert performance.

The choice of soloists over that time is perhaps less clear-cut. In a series where the sacred cantatas were presented chronologically, he drew on a group of Japanese singers who – perhaps because of the less technically demanding coloratura of the early cantatas – could serve him well. These were unknown voices in the West but their fresh and generous-spirited aria singing helped to give Bach Collegium Japan a distinctive and persuasive cultural ‘take’ on Bach. At the height of the more self-conscious end of early music orthodoxy, here was singing that was rarely arch or mannered, and often disarmingly sympathetic to the prime message of the text. Soprano Midori Suzuki – no relation – was an early standard-bearer (recalling a bright-eyed and guileless reading of Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut) and the affectingly fluid and flexible sound of Yoshikazu Mera rarely failed to impress (his Widerstehe doch is a marvellous depiction of the wiles of the devil). He soon left to pursue a career in various popular idioms.

Gerd Türk and Peter Kooy were the European stalwarts around whom only two other Japanese singers featured regularly: Makoto Sakurada – a singer of great dedication but for whom the technical gymnastics of some cantatas were occasionally a stretch too far – and the accomplished Yukari Nonoshita, who was to become the most regular and trusted of Suzuki’s home-grown singers. With a relatively small indigenous pool of Baroque expertise, Suzuki turned to distinguished alto Robin Blaze, alongside a flurry of established European singers among whom Carolyn Sampson became increasingly influential, as did Hana BlaΩíková in the final furlongs of the project.

Collegium Japan’s stately release schedule of around only two releases per annum allowed for a type of attentive immersion that distinguished it from the more pragmatic library-building exercise of Ton Koopman. The often dazzling individual and collective impact of Amsterdam Baroque cannot be under-estimated, but there is a feeling that Erato was keen to press on – the series only took a decade to complete – often using studio time to stitch different cantatas together with efficiency, if not always the same level of enquiry. Gardiner’s ‘pilgrimage’ had sui generis constraints by dint of following the liturgical calendar in that relentless schedule of 2000, but at its best provided us with virtuosic, thrilling and some touchingly immediate and spontaneous performances.

With both sacred and secular cantatas included in this grand box-set (65 of the 78 discs), Suzuki offers unrivalled consistency. If this is the reward for the andante pacing of the releases and meticulous consideration given to each work, critics have sometimes alighted on aspects where collective discipline and homogeneity become excessively deployed to the point where some of the more audacious theatricality or emotional risk in Bach’s music is absent. One sensed a tendency – especially in the earlier volumes – for over-regulated phrasing and bowings, and disembodied bass lines not quite powering the music’s emotional engine. Any bumps in the road tended to be because Suzuki’s musicians were less geared towards those rhetorical moments where rugged grip is demanded. For example, the great Cantata No 25 is decidedly passive for such stark, sin-infested imagery, and the sinewy drama of the Dragon aria in No 130 feels more represented than inhabited.

For all these intermittent peccadillos, the wonders of this series outweigh the limitations by a very considerable margin. There are some vital points in the topography of the cantatas where the most infectious qualities of Bach Collegium Japan become consistently embedded. Vol 10’s trio of masterpieces, Nos 105, 186 and 179, reveals the characterful purpose, empathy and elegance that were to become regular hallmarks. This volume showed Miah Persson’s classy credentials in No 105 alongside an example of Peter Kooy’s superb way with accompanied recitatives. In Vols 21 and 22, there are also masterly performances. In the former, No 65, ‘All they from Sheba come’, is an Epiphany cantata whose score is a rack of spices from the east, tangy horns with shepherds’ pipes (recorders) and burbling reeds (oboes da caccia) as the Wise Men set off for Bethlehem – and you can smell the Byzantine trade routes in Bach’s score and Suzuki’s adroit depiction. In No 94 in the succeeding volume, the transience of life under the gaze of man’s vanity is presented in a beautifully layered sprinkle of cascading flute and violin triplets – so assuaging and with those greatest Suzuki gifts of humility, allied to infectious warmth and humanity. Suzuki gets to the heart of the music most naturally in those works where spiritual reflection on the Word dictates the over-arching conceits. No 139 is an exquisitely unfolded, voiced and sensitive portrayal of how happy man would be if he abandoned himself to God ‘like a child’. Hitting the mark becomes an increasingly regular occurrence after Vol 32, where some less obvious showpiece cantatas, such as No 123, are so persuasively distilled and crafted that they become imprinted on one’s memory as ‘go-tos’.

It is perhaps unsurprising that authority grows through any enterprise of this kind; where diffidence originally lurked in passages of visceral emotion, there are moments from the mid-Vol 30s where heft, declamation and even a sheen of proto-Romanticism enter the sound picture. No 1, that glory of the brightly shining star, conveys the far-reaching and evocative palette of Fritz Lehmann’s pioneering reading of 1951. It is fairly brimming with love and – as in my desert-island Vol 46 (from the bumper Trinity season of 1726 of Nos 45, 102, 19 and 17) – we have those longed-for bass lines taking the music by the scruff of the neck. Vols 52‑55 contain mesmerising late cantatas in performances of beautifully judged contemplation.

In addition, the secular cantatas must be the most singularly distinguished collection on record. Koopman’s are hit-and-miss and Gardiner had other fish to fry after his Pilgrimage. This dazzling oeuvre of kaleidoscopic imagery springs off the page with Suzuki, the choral singing responsive yet disarmingly convivial, and the arias brim with personality. No 206, for the birthday of the Elector of Saxony, is a typical delight where four rivers compete for the top place in the monarch’s favours. Hana BlaΩíková is ravishing in her gently emboldening aria ‘But listen to the choir of gentle flutes’ – three flutes imploring the rivers to work together with undivided concord and sweet harmony. Mention must be made of Carolyn Sampson’s unyieldingly accomplished singing in that tour de force of a soprano cantata, No 210, which sits joint first with Dorothea Röschmann (Dorian).

Much has been written about the flurry of outstanding Passions in the pandemic and since, with Suzuki’s most recent recordings of the St John and St Matthew Passions sitting at the apex alongside the exceptional readings of Philippe Herreweghe and Raphaël Pichon respectively. Bach Collegium Japan’s St John Passion is significantly more rewarding and multidimensional than his earlier version of 1998. This is a profoundly rich statement of a work which pours out radiantly from Suzuki’s head and heart, although it is the St Matthew Passion (which won a Gramophone Award in 2021 and far outshines the earlier recording of 1999) that most extraordinarily brings together a lifetime of dedication to Bach. Alongside Pichon, Suzuki’s fluent coalescing of inward devotion and visceral drama also offers, unusually, a prescient consolation of redemption in its glowing peroration. The oratorios and the four Lutheran Masses (and a plethora of attractive miscellany, such as Schemelli’s Songbook) don’t reach those heights, but the sum of these 78 discs punches as high as any major collection of Bach’s oeuvre on record.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe to Gramophone today