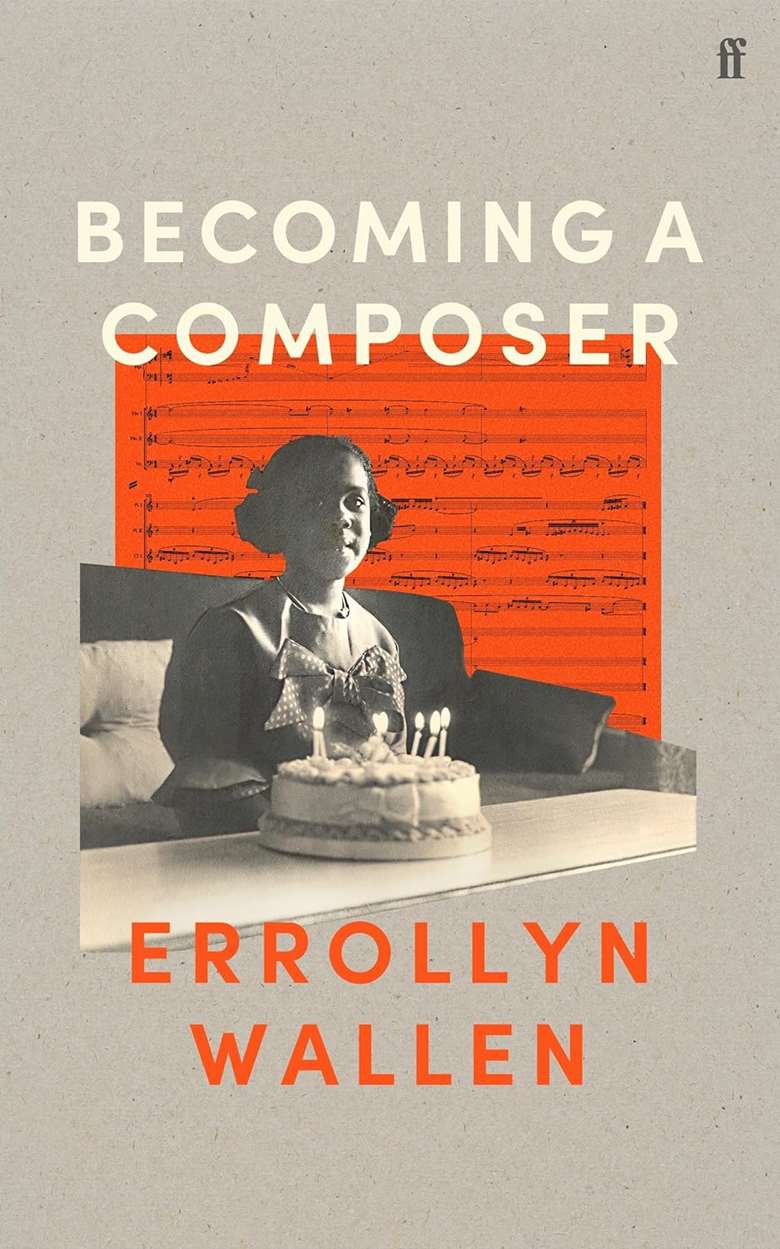

Becoming a Composer by Errollyn Wallen | Book Review

Leah Broad

Monday, February 5, 2024

Errollyn Wallen's captivating memoir gives a glimpse into the world of composers through authentic and accessible dialogue

Register now to continue reading

This article is from Opera Now. Register today to enjoy our dedicated coverage of the world of opera, including:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to Opera Now's news pages

- Monthly newsletter