The Merry Widow at Glyndebourne: ‘I put all my best jokes upfront and try to find even better ones for later. I want to send the audience home euphoric’

Michael White

Thursday, April 4, 2024

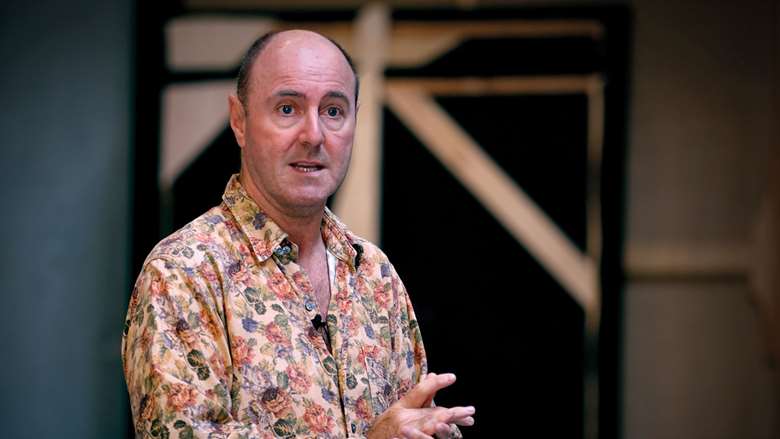

Director of Glyndebourne’s new production of The Merry Widow, Cal McCrystal talks about the sometimes not-so-subtle art of making opera funny

There’s an old Bugs Bunny cartoon with the punchline ‘What d’ya expect in opera, happy endings?’ – and it plumbs the depths of a profound truth. Comic opera features widely in the repertoire, but is it always funny? Doesn’t the default position of sung drama tend toward distress rather than laughter? And if that’s true, isn’t it an uphill struggle to make opera audiences rock with mirth as they approach their 57th Barber of Seville or Falstaff – or, as will be happening at Glyndebourne in the coming season, Merry Widow?

Somebody who knows better than most is the director Glyndebourne has engaged for its Widow, Cal McCrystal. He’s a specialist in comedy, with credits that stretch from the National Theatre’s One Man, Two Guvnors to the Paddington Bear films. And Widow will be his fifth opera – following a Mondo della luna years ago, a Comte Ory for Garsington, and two notable stabs at G&S (Iolanthe and Pinafore) for ENO.

He says they have all been good experiences, and insists that comic opera is the only kind he’d ever want to do – ‘because I love the connection with the audience that laughter is, and I’d feel lonely without it. Tosca or Macbeth are not for me’. But at the same time he acknowledges the special problems that arise, and accepts that too much operatic comedy results in nothing better than polite, head-nodding titters from the stalls when modest jokes – the banter of Parisian Bohemians in their garrett or the wooziness of yet another drunken Russian peasant – surface for the umpteenth time.

‘I’ve never liked those sort of opera laughs,’ he says. ‘They’re for people to signal they’re in tune with what’s going on, rather than the real prize: the punch in the belly that I’m after.’

And how exactly do you get that belly punch? ‘There are no fixed rules, because it largely depends on the personality of the cast: I’d say 30 per cent of what I put onstage is planned from the start and 70 per cent comes out of rehearsals. But I do plot where the laughs should come, and where they shouldn’t because the music needs to register clearly. And a basic rule is that you can’t have a first half funnier than a second.’

Saving the best jokes for after the interval? ‘No. I put all my best jokes upfront and try to find even better ones for later. I want to send the audience home euphoric.’

This objective, though, comes up against a stack of challenges – the most obvious being language. If it’s not the language of the audience, you rely on surtitles. And they compete for audience attention with what’s happening onstage.

‘I try to make my shows so physical that people won’t want to take their eyes off the performers in case they miss something. But when you need the surtitles to explain things, timing is important: you don’t want them to deliver the punchline until it’s been said.’ And more broadly, timing is always critical in an art form where pace is ultimately dictated by the music, leaving the director locked into its framework.

There’s a famous story of the actor Sir John Gielgud directing his first opera and feeling so helpless as the score trundled on with the indifference of an express train, that he forgot himself in rehearsal and ran to the conductor wailing ‘Do, do, do stop this terrible music’. If it’s true, it’s understandable – and only made worse by the fact that music takes more time than speech.

McCrystal always has in mind ‘an ideal timing for a joke, but music makes it four times longer – especially in the kind of opera where the same text repeats over and over. Sometimes the only solution is to ignore the text and create some physical comedy that doesn’t necessarily connect with what’s being sung’.

This radical approach may not be purist, but McCrystal never claims to be. He tends to rewrite operatic jokes so of-their-time that they mean nothing to a modern audience: ‘It gets you into trouble but you have to do it. Humour changes through the .’ The flip side of such changes, though, is that new sensitivities creep in.

‘I sometimes feel I’m on the frontline of the battle for correctness, and it’s like walking on eggshells. I don’t want to offend anyone, for the simple reason that they won’t laugh if I do. But people are so quick to find offence these days, it’s crippling.

‘When I revived my Iolanthe, ENO gave me a sizeable list of things that had been in the show five years before but were no longer deemed acceptable and had to go. Some I fought for, some I didn’t; but it was absurd. I had a joke about Belgravia being a deprived inner-city ghetto, and was told the word ghetto couldn’t be used because one person – just one person – had written in to say they found it upsetting. What do you do?’

Something you don’t do is despair. According to McCrystal, some of the expected challenges of comic opera turn out not to be a problem after all; and one is singers being straight-laced or resistant, with a ‘Don’t-you-know-I’m-singing-a-top-C-here’ attitude.

McCrystal says this rarely turns into a major issue, because ‘even though singers can be stiff in dialogue, they mostly throw themselves into it heart and soul. We know the music comes first, not the jokes. But everyone wants to be liked by the audience, and everyone likes getting laughs’.

Another not so problematic problem is that jokes in standard rep libretti will have been experienced so often by the audience, they turn into tropes.

‘But I don’t mind that’, says McCrystal. ‘People are attracted to familiarity, it’s like an old friend coming onstage. And in opera that can be salvation. The director might have a “concept” of doing everything around a titanium orb that makes no sense, but a bit of business you know makes you feel comfortable. And if the tropes are twisted so they deliver surprise alongside the familiar, better still.’

His planned surprises for the tropes of Merry Widow are inevitably under wraps – they wouldn’t be surprising otherwise. But as the piece demands a kind of humour more sophisticated than robust, he’s ‘going for a Golden Age of Hollywood glamour approach. We’re doing it in English, with an element of pathos to raise the emotional stakes and get the audience ready to laugh or cry.

‘But there’s room for physical jokes too: the can-can dancers are a gift. In fact, it’s a fairground. I can’t wait to get in and switch on the lights.’

The Merry Widow is at Glyndebourne from 9 June to 28 July 2024. www.glyndebourne.com

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of Opera Now. Never miss an issue – subscribe today