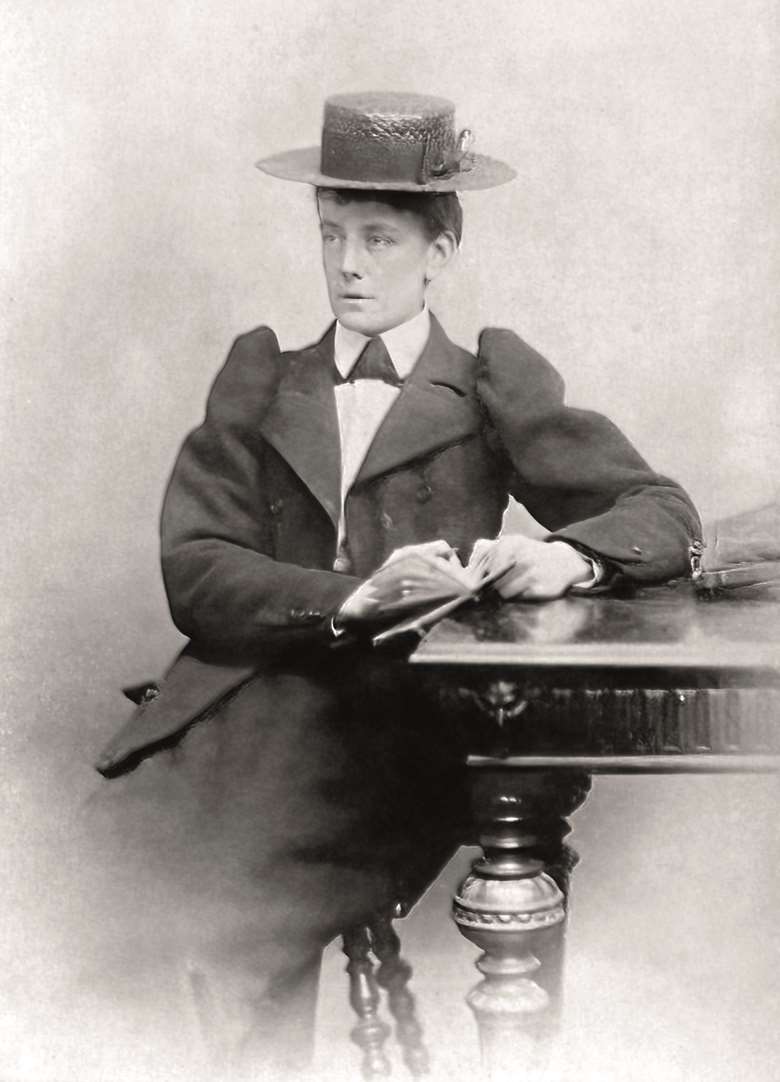

Secrets of the Forest: A revival of Ethel Smyth's 'Der Wald'

Leah Broad

Monday, February 5, 2024

Ethel Smyth's opera 'Der Wald' (The Forest) enjoys a revival thanks to a new recording by the BBC Symphony Orchestra

Register now to continue reading

This article is from Opera Now. Register today to enjoy our dedicated coverage of the world of opera, including:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to Opera Now's news pages

- Monthly newsletter