Resurrecting an English rarity: Stanford’s The Critic at Wexford Festival Opera

Jeremy Dibble

Thursday, October 3, 2024

As Wexford Festival Opera prepares to stage Stanford’s English satire The Critic, we explore the work’s history and its place in the composer’s operatic output

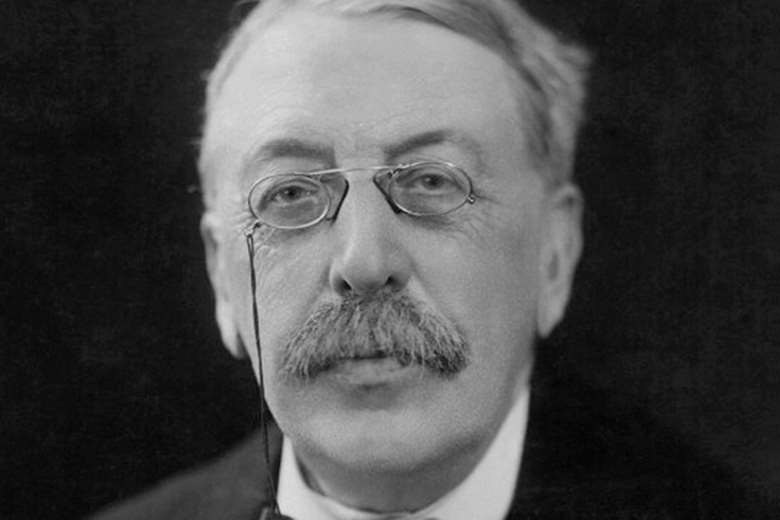

By the time Charles Villiers Stanford began work on his penultimate opera, The Critic, in 1915, he had authored no fewer than seven operas, all of which reflected not only the composer’s lifelong desire to succeed in the theatre but also his creative instinct to explore a whole range of operatic genres and styles. In his early career, he had enjoyed a degree of success with grand opera in The Veiled Prophet (Hanover 1881) and Savonarola (Hamburg 1884) even though the latter had a disastrous reception at Covent Garden under Richter (through no fault of Stanford’s) and The Veiled Prophet ended up as a victim of that lingering antiquated practice in British 19th-century opera of being performed in Italian in 1893 rather than in its original English (which Stanford ardently preferred).

The more Mozartian Canterbury Pilgrims (1885) had a fair success under Carl Rosa but his one Italian verismo opera, Lorenza (a collaboration with Antonio Ghislanzoni, who provided the libretto for Verdi’s Aida, and Ferdinando Fontana) never saw the light of day, even though it contains some of the composer’s most passionate music. Stanford’s one ‘hit’ occurred in 1896 with Irish ‘opéra comique’, Shamus O’Brien, under Henry Wood (who thought it one of the most dramatic works he ever conducted) which enjoyed a long run in London, tours around the United Kingdom, several major cities in the United States and Australia. Sadly, an attempt to repeat this operatic model in an English form, in Christopher Patch, failed to make the stage (and the libretto is now lost). Undeterred, Stanford combined his natural flair for drama and comedy in Much Ado About Nothing which, after performances in London in 1901, had an appreciative if brief outing in Leipzig. It was Shamus, however, which retained a place in the opera house, and although its staging in Breslau (where the spoken dialogue of Hiberno-English was converted, ineffectively, into recitative and German translation) had a lukewarm reception, its revival by Beecham in 1910, wisely in its original version, revitalised Stanford’s love of the genre.

The year after the revival of Shamus, Beerbohm Tree produced Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s play, The Critic: or a Tragedy Rehearsed (which had first been staged at Drury Lane in 1779) at His Majesty’s Theatre in London with a cast of celebrities. Sheridan, the doyen of the satirical 18th-century drama, based his play on George Villiers’ Restoration play, The Rehearsal (1671), which, aimed at Dryden, sought to parody the ‘puffed up’ gestures and pretentious grandiloquence of 17th-century English tragedy couched in the language of ‘sham Shakespeare’. It is also likely that Villiers drew on the model of the ‘play within a play’ (sometimes referred to ‘mise en abyme’) as presented in Hamlet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Sheridan’s targets were London’s contemporary critics and dramatists (such as Richard Cumberland) with their absurd sense of self-importance and inflated prose. He then chose to caricature these characteristics in a series of misfortunes and dramatic non sequiturs in a rehearsal of The Spanish Armada, a play by Mr Puff who invites critics to witness his new production.

Tree’s production almost certainly reinforced the admiration for Sheridan’s play among the public and Stanford, who probably knew the play from his youth in Dublin, evidently saw an adaptation of it as an opera, and a chance to experiment with a genre he had not yet tried, the burlesque (one which had enjoyed a major vogue in Victorian London at the Gaeity and Royal Strand Theatres), as something not to be missed.

With the help of the actor, Lewis Cairns James, who assisted as a teacher of acting for Stanford’s opera class at the Royal College of Music, Sheridan’s satire was honed into two acts, and, with a backward glance to the 17th-century world of Villiers’ play, a concluding Masque. It was, as Stanford explained to his friend, Robert Finnie McEwen, ‘the queerest opera you ever saw and to the best libretto I ever had! Sheridan’s Critic. I wonder no one ever did it before.’ Purely spoken parts were allotted to actors, Puff, the playwright, Dangle, the composer, Sneer, the critic, the underprompt, and to Mr Linley, the conductor; the rest of the cast were for singers, some of whom doubled up in two roles. As if to point up the Puff’s eccentric imbalance of the drama, a male chorus only appears in the first act. In adapting the play, Stanford stipulated that the actors and singers should in no way be tempted to ‘ham up’ their roles: ‘This Opera is meant to be played, as the original should be, in all seriousness. Any attempt to treat it farcically only spoils the humour of the play.’ From the outset he took the opportunity to build on Sheridan’s biting satire, and, emulating the manner of 19th-century burlesque, used music and musical quotation to heighten the pervasive atmosphere of caricature, though subtly treading a fine line between sarcasm and disproportion.

An overture (an early instance of aleatoricism), instructed to be brief, where players should practise passages from the work at leisure while ensuring that ‘Auld lang syne’ (which appears prominently in Act 1 in the minor), is a prime example. There are hilarious citations from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (for the overblown Beefeater), strains from ‘Rule, Britannia!’ (in keeping with Sheridan’s own reference to Arne’s aria from his masque Alfred) and a minuet from Handel’s Ariadne. Handel’s chorus ‘See the conquering hero come’ (originally from Joshua but later better known from Judas Maccabeus)and Stanford’s own ‘Drake’s Drum’ from his Songs of the Sea also coalesce in the conclusion of the Masque, and with the death of the ill-fated Don Whiskerandos, his final utterance ‘O cursed parry’ ushered forth the opening choral phrase of Blest Pair of Sirens, a work which Stanford had premiered with the Bach Choir in 1887.

Stanford’s comical dialogue is lively and inventive as is much of the original music for the opera. This is attested by Act 1’s grand ensemble, and Tilburina’s delicately scored ‘nature aria’ (‘Now has the whisp’ring breath of gentle morn’) which turns into a bizarre horticultural and avian tour – all of this while she experiences a vision of the forthcoming battle and launches into a sumptuous love scene with Don Ferolo Whiskerandos, the fictitious and imprisoned son of the Spanish admiral who has fallen in love with his ‘beauteous enemy’. Act 2 builds on this bizarre, unlikely catalogue of events with a trio for the Justice, his wife and their long lost son, an over-truncated soliloquy for the Beefeater (whose love for Tilburina is unrequited), a mimed ‘Intermezzo (alla Ceciliana)’ for Lord Burleigh which is essentially a ‘concertante’ movement for solo viola and orchestra, a song for the Beefeater (‘Am I a beefeater now?) showing his muscular resolve to act, the death of Don Whiskerandos (a skit on the classical ‘death scene’) and Tiburina’s ‘Scherzino pazzo’, an emotional ‘helter skelter’. This is followed by the entirely orchestral ‘Masque’, a depiction-cum-pageant of the Armada battle and the English victory.

The Critic was first performed at the Shaftesbury Theatre on 15 January 1916 under the aegis of the Beecham Opera Company. The Sketch enthusiastically hailed Sheridan as the ‘ancestor of Gilbert’ and ‘Stanford as his Sullivan’. Its run of 11 performances was undertaken by one of Stanford’s former pupils, Eugene Goossens. Two further performances took place at the Aldwych Theatre in May, again under Goossens’ direction before transferring to Manchester, where Stanford attended the last of the three performances on 2 June. Part of the Masque was recorded by Stanford for HMV in 1916 at its Hayes studio in November. At a date after this, he evidently elected to augment the Masque with a Falstaff-like ‘farewell’ appearance from the soloists. This has never been heard before and is included in Wexford Opera’s four performances of the opera in October and November this year to mark the centenary of Stanford’s death (in an edition by myself). As one critic commented in The Standard after the first performance: ‘What did not pass us by, despite diverting exteriors, was the real value of the music…[which] is of rare texture, both in construction and dramatic power.’ It should be a revival well worth attending by a composer whose natural affinity for the stage has been unjustly neglected. ON

The Critic by Charles Villiers Stanford is at Wexford Opera Festival 19 October -1 November. wexfordopera.com

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Opera Now. Never miss an issue – subscribe today