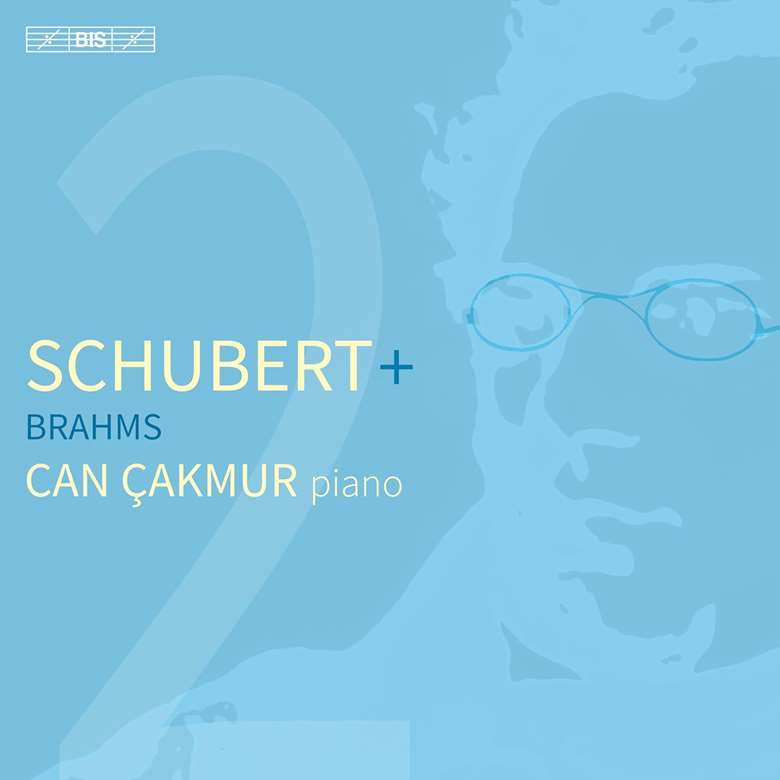

‘Schubert + Brahms’ – Schubert: Impromptus, D935. Drei Klavierstücke, D946. Brahms: Klavierstücke, Op 119 (Can Çakmur)

Bryce Morrison

Friday, March 8, 2024

It would be difficult to imagine a less evasive Schubertian, or one who turns such an ironic eye on the amicable and domestic world of the ‘Schubertiads’

‘Schubert + Brahms’ is the second issue in a projected series showing Schubert in often-surprising relation to other composers. The case for Schubert’s prophecy is made acutely clear in Çakmur’s accompanying notes, and his previous album, dedicated to Schubert and Schoenberg, underlines his point. Schubert and Brahms may be a less radical combination but the two composers’ sharing of a profound and unsettling emotional ambiguity is made crystal-clear.

And it is this central quality, whether at times savage in Schubert or bittersweet in Brahms, that Çakmur captures to a rare and audacious degree. Already, at the age of 26, he is an artist of rare perception. Invariably, there is that sense of benign ideas clouded over with page after page perceived, as it were, ‘through a glass darkly’. And it is in this sense that it would be difficult to imagine a less evasive Schubertian, or one who turns such an ironic eye on the amicable and domestic world of the ‘Schubertiads’ (the play-through by friends of music beyond their comprehension).

Opening with the second book of Impromptus, D935, Çakmur is gratifyingly straightforward in No 2 yet never without those subtle and ear-catching details, that acute sense of harmony and rhythm that come to seem inseparable from his playing. In No 3 he finds all the wistfulness of the ‘Rosamunde’-based theme and a magical hesitancy in the first variation, as if on the edge of a whispered confidence. What finesse, too, in the gently cascading Variation 4, yet with all such relative quiet banished in the final Impromptu, which is given with a snapping fury together with an uncompromising sense of the eerie.

In Brahms’s Op 119 Intermezzos and Rhapsody, Çakmur’s performance is again alive with individual touches, more peppery and sharply accented than usual in the jocular No 3, grandly rather than feverishly paced in the Rhapsody. But it is in Schubert’s Drei Klavierstücke that Çakmur finds the truest outlet for his penetrating imagination. From him No 1 is a frenetic chase against the clock and can rarely have sounded more driven or agitated, while in the central section you are once more reminded of how Schubert’s volatility could rise to the surface when you least expect it. In No 2 a benign opening is quickly clouded by music of a rhetorical menace, while few pianists have achieved a more intense stress on the darting cross-rhythms of No 3.

Very much in the early stages of his career, and with triumphs in the Hamamatsu and Scottish International Competitions well behind him, if Çakmur finds himself in the company of such celebrated Schubertians as Kempff, Brendel, Lupu and Perahia (to name but four), he makes his mark in his own singular way. If Kempff, a great if radically different Schubertian, resolves Schubert’s pain in sublimity, Çakmur convinces you no less of a visionary and troubled spirit.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of International Piano. Never miss an issue – subscribe today