Review - Sir András Schiff’s complete Decca recordings

David Threasher

Friday, November 22, 2024

David Threasher welcomes a celebratory box of Sir András Schiff’s complete Decca recordings

Shortly after I received this handsome set, Sir András Schiff withdrew due to injury from his appearance at this summer’s BBC Proms, at which he had been due to perform The Art of Fugue. These late-night Bach concerts have become something of a mini-tradition over recent years, exploring repertoire that Schiff has also revisited on record in a series of high-profile recordings for the ECM label. They also boast the slightly mystical aura that has come, to a certain extent, to accompany the man himself. Always an independent (and occasionally outspoken) thinker – on matters that go beyond the merely musical – he has fed this image through his increasing penchant for not announcing his concert programmes until the last minute, for accompanying his performances with impromptu commentaries and for playing on an array of modern and period instruments that ranges far beyond the standard Steinway.

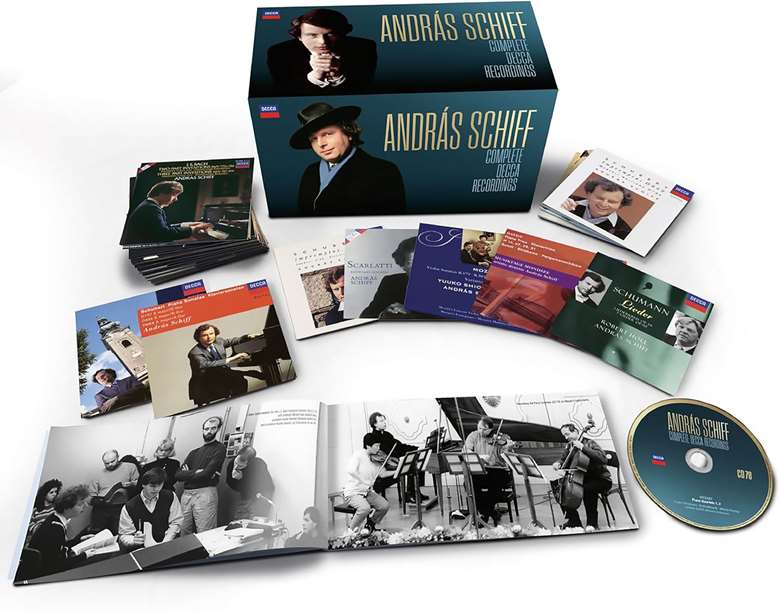

Still, this substantial box of delights should cheer Sir András’s spirits while he recovers from his broken leg. The presentation is attractive and the contents comprehensive, to the extent of supplementing the domestic catalogue with recordings of Beethoven’s violin sonatas (with Sándor Végh) that were previously available only in Japan. Schiff made his first recordings for Decca in 1979 and was associated with the label for a decade and a half. The result is a hefty box of no fewer than 78 discs, tracing his musical concerns over this period as solo pianist (discs 1-31), concerto soloist (discs 32-51), chamber musician (discs 61-74) and song accompanist (discs 52-60); the last four discs cover his first significant encounter with 18th-century instruments as he explored Mozart’s solo, duo and chamber works on the composer’s own piano.

Bach naturally figures prominently. During the early 1980s, when Schiff recorded a number of the larger works and sets, arguments over the suitability of the piano for Baroque music raged more fervidly than they do today. Early reviews took Schiff to task for a romantic – and even ‘Schumannesque’ – approach to Bach, lingering over phrases and applying a degree of rubato that some thought inappropriate. It’s unashamedly pianistic, make no mistake, as is a sole disc of Scarlatti sonatas. The passage of time, though, has broadened our perceptions of Bach performance practice to the extent that the impression today of Schiff’s Bach is not of anachronism but of intellectual clarity warmed by genuine love for the music. The counterpoint is never obscured and a generous policy of repeats gives rise to telling and generally tasteful ornamentation. As for the concertos, Schiff’s collaboration with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe offers a prime choice for modern-instrument readings, even if the two- and three-keyboard works with Peter Serkin, Bruno Canino and Camerata Bern lay all too bare the problems of matching Bach’s music to a congregation of concert grands.

Mozart and Schubert figure as significantly as Bach in Schiff’s Decca discography. Among his earliest recordings for the label were the Mozart sonatas, joined a few years later by a disc’s worth of smaller works. Schiff recalls the sonata sessions as notably happy ones, and the audible pleasure he took in these works is similarly evident in a leisurely cycle of the concertos. Recorded balance improved in later sessions, so that a somewhat recessed piano on the 1984 disc of Concertos Nos 17 and 18 becomes a touch more present in the mix by the time of, say, the 1988 Jeunehomme. One particular bonus in this cycle – quite apart from Schiff’s stylish pianism – is the beauty and sensitivity of the wind-playing: Sándor Végh’s Salzburg Camerata Academica was primarily a string ensemble, so the presence of wind and brass guests such as Aurèle Nicolet, Heinz Holliger and Radovan Vlatković adds extra lustre to this desirable concerto survey.

A collaboration with Georg Solti and Daniel Barenboim in the three-piano K242 yielded less sympathetic results but there are further treasures in a supremely classy Quintet, K452 (Holliger, Elmar Schmid, Klaus Thunemann, Vlatković), here recoupled with Beethoven’s Op 16 Quintet, and a cherishable Ch’io mi scordi di te with Cecilia Bartoli. Later on Schiff revels in the colours he is able to draw from Mozart’s own fortepiano, not only in a selection of sonatas and solo works but also in some dramatic violin sonatas with his wife, Yuuko Shiokawa, piano duos with George Malcolm, thrillingly pushing the poor Walter to the very threshold of its abilities, and piano quartets with Shiokawa, Erich Höbarth and Miklós Perényi.

Schiff trailed his Schubert sonata survey with a pair of discs of shorter works, in which the lyrical impulse that lies behind so much of his playing is on full display, despite some occasionally flouncy ornamentation. It is in the sonatas, though, that traces of what some perceive as a certain degree of mannerism or preciousness creeps in, which seems at times to impede the flow of the music. The value of this sonata cycle, played on a luminous Bösendorfer Imperial, lies primarily in its comprehensiveness and the inclusion of a generous handful of unfinished and fragmentary works. Nevertheless, the more established later works are better served by the more recent ECM remakes.

It’s interesting to note what music Schiff chose not to incorporate into his recording repertoire at this time. There’s conspicuously no solo Beethoven: Schiff got round to the concertos in 1996 with Bernard Haitink (on Teldec) but was adamant that he wouldn’t record a sonata cycle until he turned 50 (in 2003). He held to his word, setting them down for ECM in instalments following extensive tours and over the following five years produced a sequence as stimulating and provocative as any made this century. The violin sonatas with Végh were clearly a labour of love for the two musicians, although the violinist was coming to the end of his playing career and lapses in intonation and coordination make this cycle one with appeal only to completists.

Perhaps surprisingly for a Hungarian-born musician, there is no Liszt, apart from a song selection recorded early on with soprano Sylvia Sass. Nor is there any solo Schumann or Chopin, although, once again, there is a disc of Schumann lieder with bass-baritone Robert Holl, in which Schiff proves himself – as throughout all nine discs of songs here – an acutely responsive and sensitive accompanist. Concertos by Schumann and Chopin (No 2) with the Concertgebouw under Antal Dorati don’t catch fire as readily as a Brahms First with the Vienna Philharmonic playing on the edge of their seats for Solti. Rounding out the concerto section of the box, Schiff dazzles in Dvořák’s Piano Concerto, advocating fervently for the notoriously challenging original version in a live performance from the Musikverein with the Vienna Philharmonic under Christoph von Dohnányi. The coupling here is a glowing Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato, while Schiff and Solti deadpan through an effervescent reading of the Variations on a Nursery Theme by Dohnányi grand-père.

Haydn, too, is absent from the solo section of the box, although there are two discs of piano trios, perceptively played by Schiff and Shiokawa with cellist Boris Pergamenschikow in performances linked to the Musiktage Mondsee, the festival the pianist founded and ran for a decade from 1989. Also connected to Mondsee are a valuable selection of solo and chamber works by Janáček – music in which Schiff appears to be ideally at home, returning to the Sonata and solo works a couple of decades later for ECM. At the other end of the scale, a selection of Mendelssohn Songs without Words finds Schiff on graceful, unfussy form in an enchanting pendant to his frothy pair of concertos with Charles Dutoit in Munich.

The Mondsee musical encounters gave rise to a series of relaxed chamber recordings through the 1990s. Earlier still, though, three-quarters of the young Hagen Quartet joined Schiff and bassist Alois Posch for a gemütlich, unhurried Trout Quintet, while players from the New Vienna Octet collaborated in Brahms’s Clarinet and Horn Trios. In all Schiff’s chamber music-making there is a sense of intimacy, of music genuinely being shared among friends. Occasionally this translates into a slight lack of momentum, of tempos that linger when they might usefully press on. Not so, though, in a driven Dohnányi pairing of the First Piano Quintet and Piano Sextet with the Takács Quartet and friends – a nearly all-Hungarian exercise that was an important stage in the wider public appreciation of the composer’s chamber works. Schiff and the Takács also get fully to grips with the strenuous passions of Brahms’s Piano Quintet.

Two discs of Bartók present warm, affectionate performances of the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion with Bruno Canino, the two violin sonatas with, respectively, Shiokawa and Lorand Fenyves, and Contrasts with clarinettist Elmar Schmid and violinist Arvid Engegard. Holliger’s presence gave rise to a somewhat knottier and less characteristic excursion into more recent music: the oboist’s own Quintet for piano and winds alongside Elliott Carter’s equivalent and more rebarbative counterpart, and works by Dorati (Duo concertante) and Britten (Temporal Variations and Two Insect Pieces) specifically showcasing Holliger’s own blazing musicianship. Then there are the songs. The calibre of Schiff’s collaborators – Bartoli, Sass, Holl and Peter Schreier – tells its own story, and it was with Schreier that Schiff shared the Gramophone Solo Vocal Award in 1991, for their highly regarded recording of Die schöne Müllerin.

The 78 discs come in original-jacket cardboard sleeves. The glossy and substantial booklet contains not only comprehensive track-listings and recording information but also an interview between Schiff and Misha Donat brimming with candidness and insight, as well as some revealing session photos. Considered as a whole, this set is testament to a musician who should without demur be considered among the leading pianists of our age.