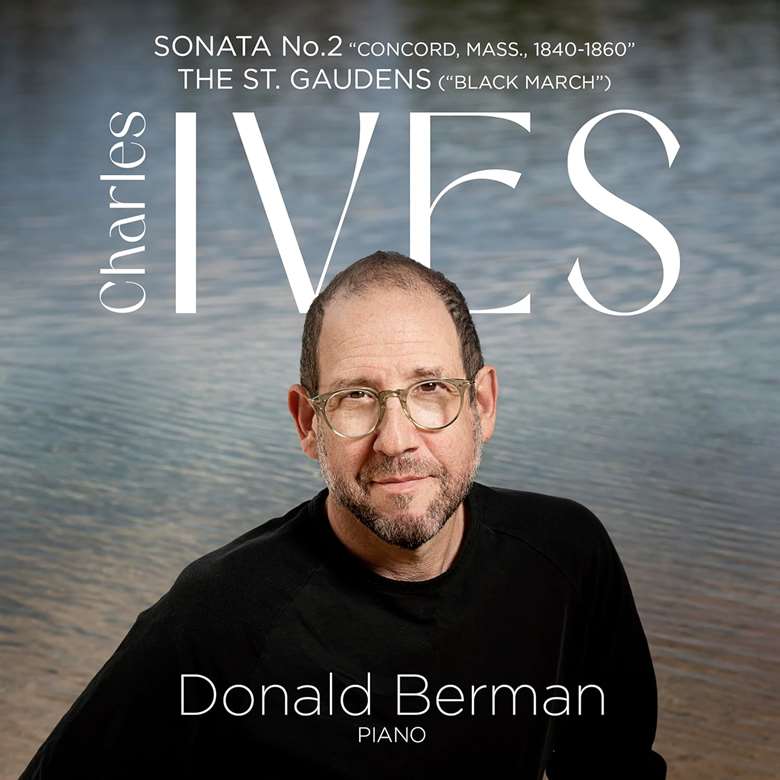

Review - Ives: Piano Sonata No 2, ‘Concord, Mass, 1840-1860’. The St Gaudens ‘Black March’ (Donald Berman)

Richard Whitehouse

Tuesday, September 24, 2024

This is Ives interpretation at its most perceptive

Live performances may still be relatively infrequent, but Ives’s Concord Sonata now enjoys a sizeable discography that features a wealth of interpretation. The general interpretative direction is one of repositioning the work from a harbinger of modernism towards a culmination of late-Romanticism, with Donald Berman demonstrably following that trajectory. As he suggests in a thoughtful booklet note, his underlying concern has been to open out the music’s expressive range by emphasising the improvisatory aspect that the composer increasingly advocated.

This is most evident in the opening ‘Emerson’ movement, which incorporates the first of the Four Transcriptions from ‘Emerson’, motivically enriching the music while also dissolving its perceived formal boundaries into the seamless unfolding of emotional tension and release. That said, Berman’s use of additional material is less striking than his intensifying of its dialectical nature towards a coda that still affords the requisite catharsis. Nor is there any lack of impetus in ‘Hawthorne’, the whimsicality of its trios ideally integrated into the overall abandon, with the heady final section poised between coda and apotheosis. This is Ives interpretation at its most perceptive.

What follows might be considered less successful, but that would be to assume the soulfulness of ‘The Alcotts’ as lacking when shorn (as here) of any extraneous sentiment, or the inwardness of ‘Thoreau’ as being compromised when it is underpinned by a striving for resolution. Absence of the viola interjection in the first movement should be of merely passing concern, whereas that of the flute obbligato in the finale undeniably changes its intrinsic content; but whether this reduces or intensifies its expressive essence must be for each listener to decide.

Berman’s technical finesse is undeniable, as are his clarity and tonal allure, superbly captured by Adam Abeshouse. For comparisons, the pioneering zeal of Ralph Kirkpatrick (Sony) or scintillating pianism of Roberto Szidon (DG), and, more recently, the detached objectivity of Pierre- Laurent Aimard (Warner), the quizzical and disciplined Alexei Lubimov (Zig-Zag Territoires) and the understated Joonas Ahonen (BIS) make claims on the listener’s allegiance, which is not to deny Berman his place in their company.

For an entrée, Berman’s edition of the Urtext of The St Gaudens – later orchestrated as the first of Three Places in New England – has a pathos that ought to secure it a regular place in the concert hall. This can be warmly recommended to Ives devotees and newcomers alike.

This article originally appeared in the Autumn 2024 issue of International Piano. Never miss an issue – subscribe today