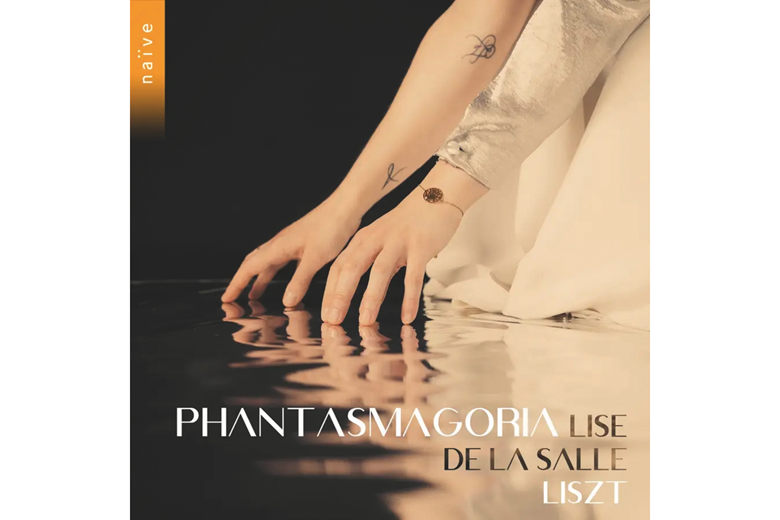

Phantasmagoria (Lise de la Salle)

Harriet Smith

Friday, March 7, 2025

That she has mastered its unique physical and emotional demands is not in doubt. Listening to the work unfold on her finely recorded Steinway, she proves a supremely confident guide

Lise de la Salle and Liszt have been musical travelling companions since her earliest teenage recordings and here is another fascinatingly conceived programme, launched by the B minor Sonata.

In the programme note de la Salle reveals that she came to study the Sonata only recently: ‘It had been in my head, my heart and my guts for some time … I only got stuck into it in 2021 but I feel like I grew up with it.’ That she has mastered its unique physical and emotional demands is not in doubt. Listening to the work unfold on her finely recorded Steinway, she proves a supremely confident guide. It’s only when you start to analyse de la Salle’s approach more closely that some cracks appear. The opening lacks the taut menace of, say, Krystian Zimerman (DG), while the dotted double octaves that launch the Allegro energico are oddly stolid, rather than having the pent-up energy conveyed by artists as temperamentally different as Alfred Brendel (Philips) and Arnaldo Cohen (BIS). Once the textures become more complex, she sounds more at home. There’s also the matter of rubato, which sometimes borders on the (to my taste) excessively dreamy – not least at the Andante sostenuto (track 4 on the album), which slightly loses its way. The Sonata’s closing moments are, though, properly seraphic.

This freedom of approach can also be found in the other two works: de la Salle fully embraces the Lento, quasi improvvisato opening of the ‘Cantique d’amour’ (the last of the Harmonies poétiques et réligieuses) but when she reaches Liszt’s quietly rolling motion in the Andante her slightly steady tempo means the music flows less freely than in Steven Osborne’s masterly account (Hyperion). Both understand the sense of song here, but whereas the Scotsman appears to be in intimate lieder mode, de la Salle is centre stage in the opera house.

In Don Juan I found myself admiring the cleanness of de la Salle’s technique rather than being caught up in the drama. As the music relaxes into the duet (track 11) there isn’t the sense of play that Cherkassky, for example, finds (on the early 1950s Cologne recording on Orfeo d’Or even more than the 1954 account on Testament), but how much more innate a storyteller he is. Hamelin (Hyperion), different again, offers a more multifaceted characterisation allied to his famed technical ease, which truly comes into its own in the Prestissimo final section.

This review originally appeared in the SPRING 2025 issue of International Piano