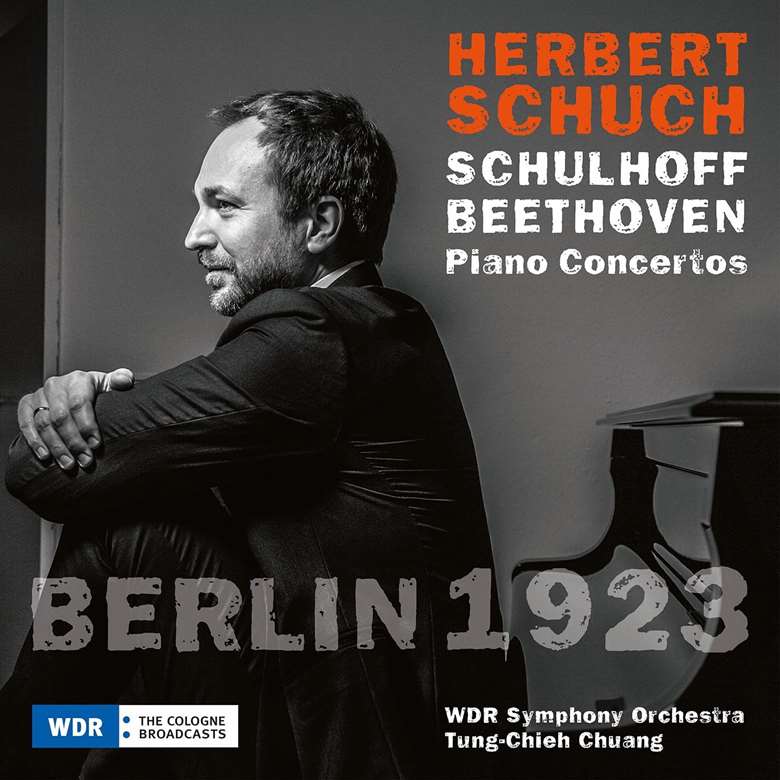

‘Berlin 1923’ – Beethoven: Piano Concerto No 1, Op 15. Schulhoff: Piano Concerto No 2, Op 43 (Herbert Schuch)

Charles Timbrell

Friday, March 8, 2024

The finale is a total success, with good dynamic variety and a marvellously rowdy delivery of the central subordinate theme

The Romanian-born pianist Herbert Schuch studied at the Mozarteum in Salzburg and is now resident in Germany. He has had an active international career in recent years and his recordings of solo works by Schubert, Schumann and Ravel have impressed me. It is a pleasure now to hear him in these two provocatively paired concertos.

Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) was an Austro-Czech Jewish composer and pianist of considerable note who wrote eight symphonies, three piano sonatas, a ‘Hot Sonate’ for saxophone and piano and a musical setting of The Communist Manifesto (1932). His very eclectic style, which often included jazz elements, was labelled ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis and he was sent to a concentration camp, where he died of tuberculosis. The unusual pairing of Schulhoff and Beethoven concertos makes some sense when we learn that Schulhoff wrote cadenzas for Beethoven’s first four concertos, all of which he performed. His Concerto No 2, lasting about 20 minutes, consists of five sections which at various times reflect influences from Debussy, Scriabin, Prokofiev and jazz. The piano part, which features ostinatos and some virtuosic chordal passages, is frequently absorbed into the very colourful orchestration. Schuch is an ardent advocate for this music, both in his playing and in his interview for the booklet.

The Beethoven concerto gets a good, solid performance that is competitive with accounts by Argerich, Pollini and others. I would like perhaps a bit more brio in the Allegro con brio but the balances are good, the orchestra is bright and alert, and the piano-playing is clean and pearly. Schuch opts for Beethoven’s long third cadenza, which was composed years after the rest of the concerto, and he responds to it with appropriately unbridled virtuosity. The slow movement is lovely, although the pianist’s softest passages could be projected a bit more. The finale is a total success, with good dynamic variety and a marvellously rowdy delivery of the central subordinate theme.

The album’s final track is a repeat of the first movement, but this time with Schulhoff’s cadenza. It couches fragments of Beethoven’s themes in an interesting new harmonic vocabulary – and it’s a lot more fun to listen to than Beethoven’s unduly serious one!

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of International Piano. Never miss an issue – subscribe today