Sviatoslav Richter: Russian revelations

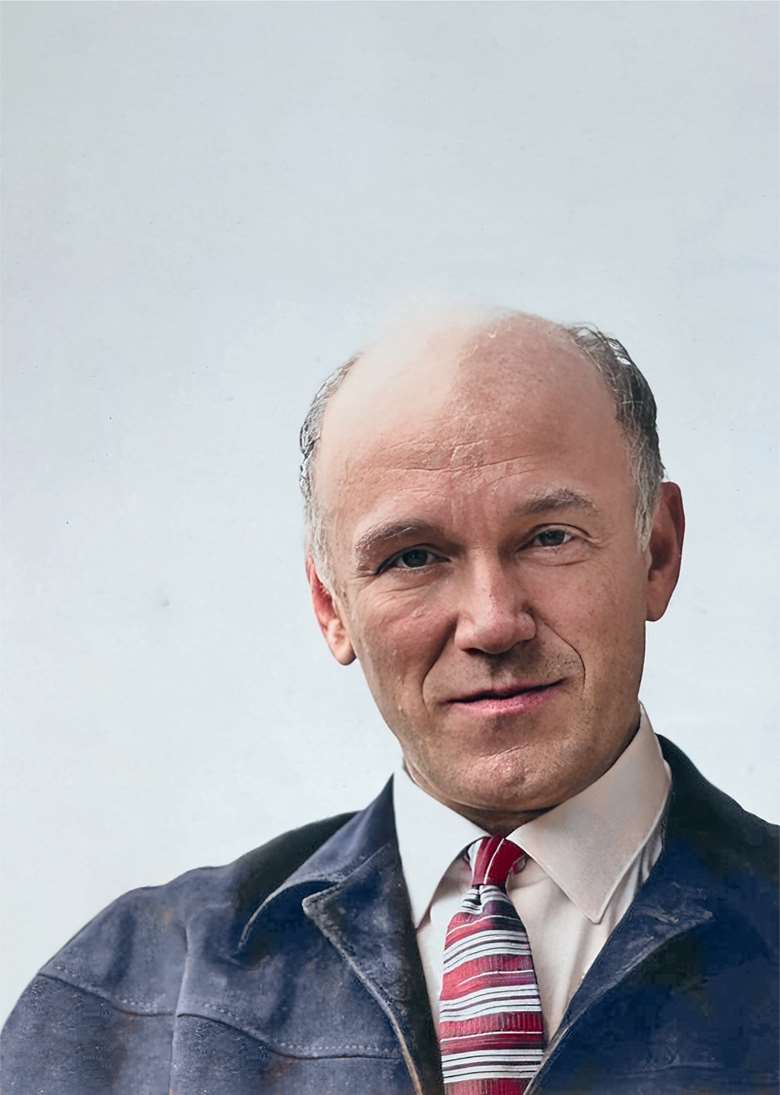

Sviatoslav Richter

Wednesday, November 2, 2022

Sviatoslav Richter offers some intimate insights into the music that inspired and challenged him, his relationship with audiences and penchant for practising at the 11th hour

TULLY POTTER COLLECTION

I do not consider it absolutely essential to have played all the Chopin Etudes. In fact I am against this playing of everything, every sonata, every study, etc. For me the exception is the Well-Tempered Clavier. As a student I suppose I studied about five preludes and fugues with Neuhaus. Later I worked at the whole work on my own. In this case I really believe that every pianist must play the Well-Tempered Clavier – and by heart as well. I do not agree with the idea that Bach should only be played on the harpsichord. One should feel free to play him on the harpsichord, but not the entire recital. Alternately with the piano is what I prefer; a whole recital on the harpsichord sounds so poor.

I am not so altruistic as to play only for the listener. No, I play above all for myself ! If it turns out well, the listener may also get something from it. A well-known musicologist once asked me, ‘Why do you always have these invisible walls round you when you play? Why don't you like the audience?’ My answer, ‘Because it doesn't concern me, I simply don't notice it.’ I am often asked, ‘How satisfied were you with the audience?’ But what is much more important is whether the audience was satisfied with me!

I play the First and Second Rachmaninov Concertos; I enjoy listening to the Third but I don't play it. Why? Because I enjoy it so much as others play it. The same is true of Rachmaninov's Paganini Rhapsody, which is also played very convincingly by others. For instance, there is a marvellous recording by Gary Graffman [with the New York Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein]. And almost every pianist who plays Rachmaninov's Third Concerto plays it well. Van Cliburn plays it well, Flier once played it very beautifully, and so did the young Mogilevsky. It is a very beautiful piece, with great charm, typical of Rachmaninov.

© TULLY POTTER COLLECTION

On my first appearance in Paris, in 1961, I first played a mixed programme of Brahms, Scriabin and Debussy. In the second concert I played Schubert: the unfinished C major Sonata and the little Allegretto in C minor, then in the second half the B-flat Sonata. And the Parisians understood it at once. The audience in Paris reacts like a thermometer; at the same time it is not primarily musical. Nor do I really like an audience that is too musical. In Germany, for example, the audience is a little too educated musically, and then it easily loses its spontaneity. A concert is then no longer an adventure, but almost a lecture.

Many pianists decline to perform unknown works. But I cannot always play the same pieces that everybody knows. For this reason I no longer want to hear the Appassionata at all; it is many years since I have played it. The last time was in 1960, in New York, and in fact very badly. I was thoroughly ill at the time. I found everything horrible on this first tour in the USA. Initially I found this other hemisphere psychologically and geographically horrible. I was afraid and did not know what I was afraid of. Before the second recital, consisting of a Haydn sonata and Prokofiev, a doctor gave me a tranquilliser. When I went on to the stage and played, and struck a wrong note, it all seemed funny to me. Unfortunately they recorded and published precisely these concerts. Later I recorded the Appassionata again in America, in the studio; it is not particularly good. I regard my Appassionata recording from a concert in Moscow as much better.

The first Schubert work I played was the Wanderer Fantasy when I was still a student and then later the Sonata in D major D850. I had once heard it from a woman student, terribly long and tedious, so that it was unendurable. I then said to myself, ‘But it cannot be possible for Schubert to be this tedious’, and I decided to play the sonata myself. What happened was what always happens with me: ‘When are you going to give your next concert?’ I was asked about that time. ‘In 20 days’ was my reply; and on being questioned about my programme I added, ‘Let's see now – Schubert among other things, the Sonata in D major’. Then I began to study it, and at the concert it went marvellously.

In the case of the Wanderer Fantasy, it was only very late in life that I succeeded in acquiring the freedom it needs. One must not play it academically; one has to take risks, as with scarcely any other work. Schubert not only had a great influence on Liszt but in my opinion had an effect, above all through the Lied, on Wagner, particularly in Die Walkiire but also in Tannhäuser.

I am quite content with the A-flat Impromptu D935 on my Schubert record of 197I. The C minor Sonata I only recorded later, but on the whole the B-flat Sonata seems to me more successful: the Scherzo and the finale are good, while the first movement is not bad either – I think it maintains the tension in spite of the enormous pauses, but they are necessary. When I play this sonata my colleagues often ask me afterwards, ‘Slava, why did you take such a slow tempo?’ Yet I do not even play molto moderato but in fact only moderato. The others always play allegro moderato or simply allegro.

I am not against composers like Saint-Saëns, whose Fifth Concerto I have played. I do not play the D minor Concerto of Brahms, but not because I should not like to; I am very fond of the first and second movements, the third less so. However, one cannot play everything. I also play only the Second Concerto of Chopin, the First and Third of Beethoven, the Rondo in B-flat and the Choral Fantasia. I have also played the Fifth Sonata of Scriabin a great deal, finally obtaining from it something I wanted: lightness and speed. I play five of Scriabin's sonatas: the Second (Sonata-fantasy) and, in addition to the Fifth, the Sixth, Seventh and Ninth.

I play both Liszt piano concertos, but his Totentanz I won't play under any circumstances; I don't like the work. This ‘Byronism’ is not to my taste! I don't like the ‘Dante Sonata’ either, and I find ‘II penseroso’ quite horrible. ‘Sposalizio’, on the other hand, is wonderful and the A-flat ‘Petrarch Sonnet’, too, is a noble work of genius which everyone unfortunately makes so banal. But a thing like ‘Chasse-neige’ again I can't stand – there is something banal about it. ‘Feux follets’ is good, but in the end also becomes a little ‘suspect’. ‘Liebestraum’ and ‘Harmonies du soir’ are marvellous and ‘Wilde Jagd’, while somewhat à la Meyerbeer, is really good – moreover the piece has a little of the Wanderer Fantasy in it.

Of Liszt's Transcendental Etudes I play eight in all: ‘Preludio’ – it is like a curtain-raiser – the marvellous A minor piece, ‘Paysage’, ‘Feux follets’, ‘Eroica’, ‘Wilde Jagd’, the F minor study and ‘Harmonies du soir’. I have also played them in this order in the first half of a recital. The other studies are not in my repertoire. I find ‘Mazeppa’, for example, much better in the orchestral version. I am fond of all Liszt's symphonic poems, especially the first, the very beautiful Bergsymphonie, but also Orpheus, a work of genius, and Hamlet. The B minor Sonata is a piece of extraordinary genius!

I am not so altruistic as to play only for the listener

On the day of a concert I always like to practise for three hours, and then do whatever I want; before the concert perhaps another 30 minutes or an hour playing. What is important above all is not to eat too much! Sometimes when I have done little preparation the concert has gone well, perhaps precisely when I have done things one should not do. There are no rules for this. I should like best to plan my concert life in this way: I would practise for a month, and after that, for a month or a month-and-a-half, play just two recital programmes, or a concerto, almost every day; and then have another break.

Unfortunately, however, when I am giving concerts I am always learning something new, because there are always commitments. But that, of course, is partly one's own fault. If, for instance, I have a month in which to prepare something I again do hardly anything at first, and only really start in the final week. And then once more the time is very short. In principle I always want to do it differently but I never succeed. It has always remained as it was the first time I played the Sixth Sonata of Prokofiev – everything at the last moment! When I have no fixed date for a concert I cannot work either, I can't force myself do it. But then when I have to, when there is hardly any time left, everything comes together of its own accord, as it were, in the final days. Then I am in a very special mood.

This article originally appeared in the Autumn 1997 edition of International Piano Quarterly, reprinted from Musiker im Gesprach: Sviatoslav Richter by permission of Peters Edition, London. English translation by John Nowell