Returning to the Piano: IV – Touches (Part 2)

Murray McLachlan

Wednesday, November 2, 2022

A technical refresher course for recommencing piano enthusiasts, created for International Piano by Murray McLachlan

Beyond literal legato

We finished the last instalment with an etudette for the cultivation of overlapping fingerwork and finger substitution. As mentioned, there is a whole stylistic gamut of ‘legato’ to consider away from this approach – pianists can explore an infinite range of delicious possibilities, including touch that does not involve any finger overlapping whatsoever. If you can keep the texture light in the bass, it is often possible to hold the pedal down for long stretches of time, allowing a legato melody line to emerge ‘smoothly’ with the fingers separate, playing ‘off’ the keys.

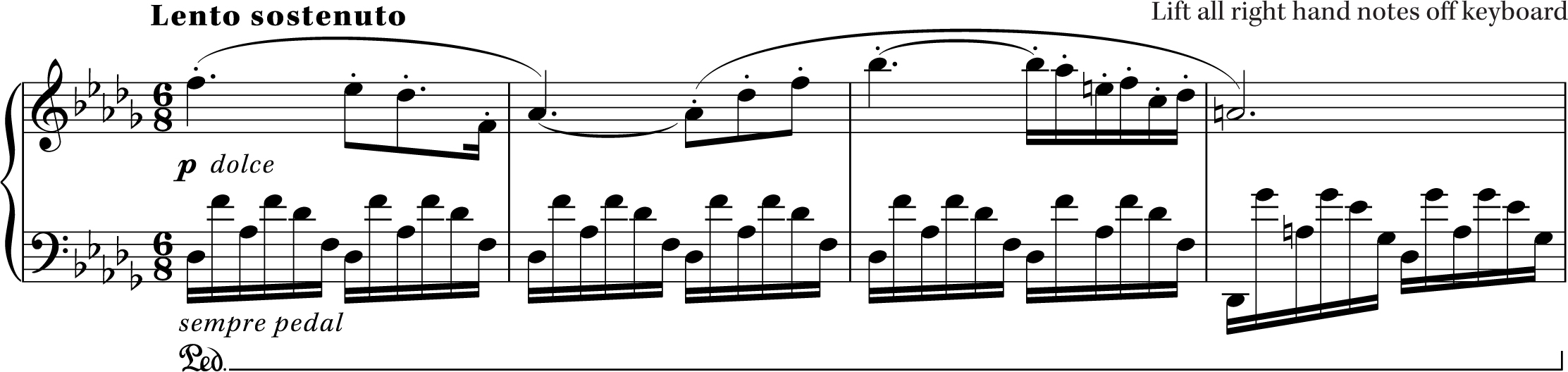

Example 1 (below) comes from the opening of Chopin's D-flat Nocturne Op 27/2. It could be played with a traditional ‘physical’ overlapping legato approach and careful pedal changes – or it could be approached as illustrated.

Example 1 Chopin Nocturne in D-flat major Op 27/2, bars 2-5

If we carefully and neatly overlap each note in the right hand, then the sound will be uniformly disciplined and constrained. This is a sensitive, caring way to tackle Chopin which is diametrically opposed to the lifting illustrated in the example. We are using a form of ‘fake’ legato in that the fingers are lifting off the keys – even though the sounds connect. Here the pedal allows for sufficient legato while the right hand's release from the keyboard gives the sounds a floating, carrying power similar to that which actors achieve when ‘throwing’ their voice. Both versions are valid and convincing – provided the pianist's ears are focused and the sounds emerge with conviction. Critical self-listening in the practice studio is crucial here, as indeed it is for virtually all technical development.

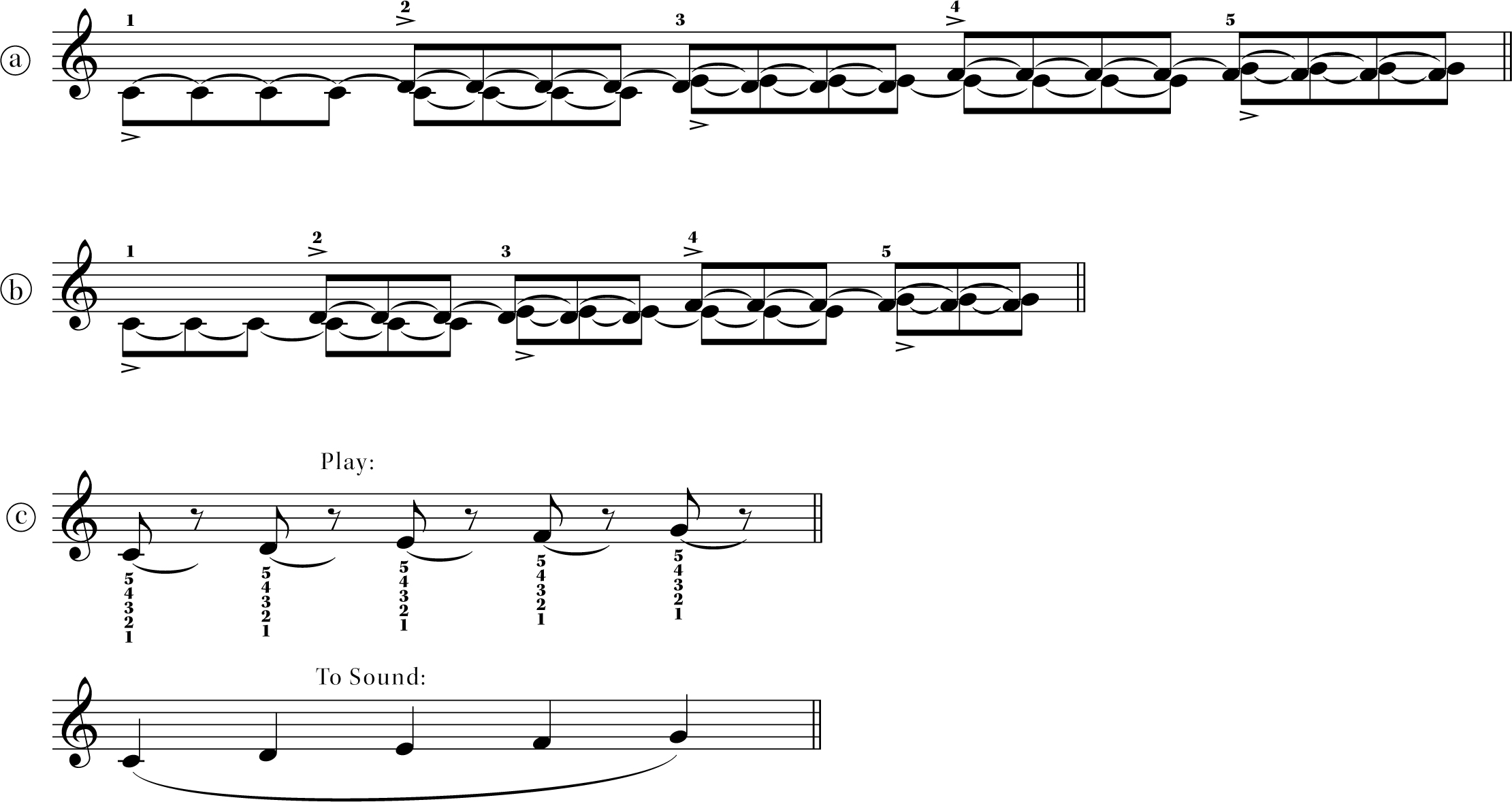

Next, let's try to make some different versions of ‘legato’ work using the five-finger pattern in Example 2. Play them back-to-back, practising each hand in turn separately.

Example 2 Legato scale patterns

The final exercise should be tackled with each finger separately in turn. Don't panic and move with contorted stiffness: this is not an exercise in literal overlap. Freedom of movement and a relaxed aesthetic should prevail as one sound dovetails sonically into the next. Finger-legato work is especially important if Bach fugues are to be learnt without the use of the sustaining pedal at every awkward corner. If the sound at the end of each note can ‘envelope’ into the beginning of the next note, then legato is triumphantly in place and should be celebrated as such!

Leggiero and jeu perlé: touch synthesis?

Effervescent, sparkling and exquisitely light virtuosity – ‘pearly playing’ (jeu perlé) – is immediately apparent in many studies by Czerny, as well as in substantial sections of the oeuvre of Weber and Mendelssohn. But in a broader context it is necessary to develop this approach to pianism for passages in music from JS Bach through the Viennese classics and beyond. Indeed, many a Chopinesque flourish would be unthinkable without the requisite lightness of execution this touch projects.

Jeu perlé works best with a flatter finger position than normal. Indeed, it demonstrates how varying finger curvature can have a dramatic impact on tone (the more curved the finger, the sharper and clearer the sound tends to be). Moreover, jeu perlé is the perfect way to show how all three basic touches can be blended together for musical effect. Example 3 (below) comes from the opening of Chopin's B-flat minor Nocturne Op 9/1.

Example 3 Chopin B-flat minor Nocturne Op 9/1, bar 4

If the right-hand run was realised with conventional finger legato, it would sound too earthbound and contained. On the other hand, an exclusive non-legato approach, even with pedal, risks accentuation and a sense of heaviness. The third option, staccato, may at first seem eccentric – but it is the one recommended. If the staccato touch is tempered through the use of the sustaining pedal along with articulation that is less clipped, the results will be convincing. It may also help to use flatter fingers than is considered orthodox, and to strive for a sense of quasi-legato in which each note sonically blends into the next.

CPE Bach's Solfeggietto: a touch universe

For several reasons, Solfeggietto by Bach's eldest son is ideal for helping adult returners at all levels come to terms with touch. Particularly important is the fact that this piece utilises both hands equally, requiring dexterous joins as one hand takes over from the other. In contrast, many other options for study, such as the Preludes from JS Bach's ‘48’, focus mainly on the right hand.

Solfeggietto is also valuable because it is appropriate for all pianists to play after Grade 3-4 has been reached. It can make a breathtaking encore at the end of a professional recital if tossed off at mercurial speed, or it can be played cautiously and steadily by a fledgling player as notes are assimilated and coordination patiently acquired. The fact that Solfeggietto has appeared in anthologies and syllabuses at Grades 4,6 and 7 speaks volumes – this is a piece that re-invents itself according to context, and therefore is perfect material for touch experimentation!

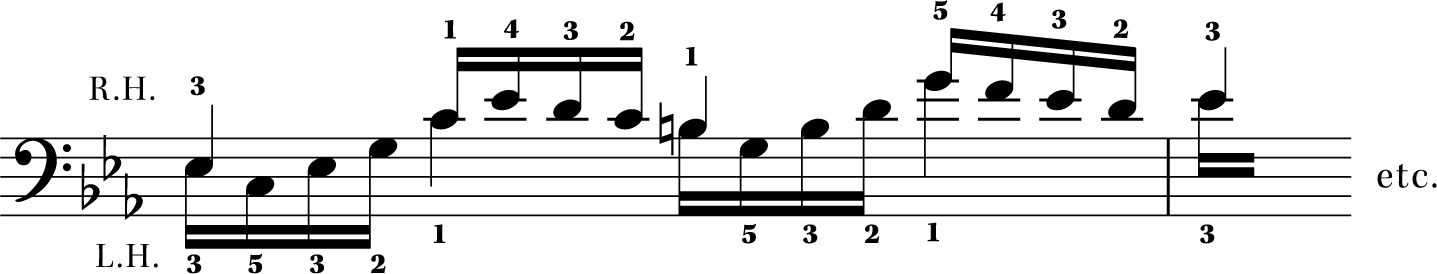

For maximum impact, try Example 4 (below) with the given hand distributions and fingerings. Begin with deep, slow overlapping legato fingerwork. It is possible to hold down the second, third and fourth notes while the fifth to eighth are being played. Try holding down three notes at a time, then two. This is the approach needed when you come to play repertoire as richly sonorous as Brahms' late Intermezzos or the slower Bach Chorales transcribed by Busoni. You can bind notes with only a gentle connection, then play with no connection at all.

Example 4 CPE Bach Solfeggietto, bar 1 (edited)

Repeat the passage over and over again, moving into light separation, gaining in speed, and finally reaching a ‘trigger’ technique whereby flourishes of eight notes at a time are articulated with light fingerwork. Use scratching movements towards the body that evoke the sound of a classical guitarist. This approach is invaluable in an enormous range of musical contexts, including Scarlatti sonatas, Bach, Mozart, Haydn and eventually bravura etudes such as the Liszt-Paganini Study No 3 in E major – a piece that can almost feel staccatissimo throughout. Similarly, the decorative right-hand arpeggiated figures in the reprise section of the second movement of Beethoven's Tempest Sonata (bars 51-58) will flow more convincingly once leggiero is experimented with in this manner.

The fact that CPE Bach's Solfeggietto works on a single line and uses both hands equally makes it perfect for developing facility that can be applied in many other contexts. Try slow, weighted work on each note, firstly with the sense that emphasis is coming directly from the knuckles. This approach could be extremely useful for Classical slow movements (try it in the opening bars of the second movement of Haydn's Sonata No 52 in E-flat major). Feel how each note is being played from your forearms or elbows, which is the approach you will require to play the whole gamut of percussive pieces from Bartók's early Mikrokosmos numbers through to advanced works such as Prokofiev's Suggestion diabolique.

Play the opening of Solfeggietto again, but this time start with the fingers off the keys. Take it at a fast tempo and ‘shake’ out the semiquavers from your sleeves. This is an excellent study in wrist staccato, which will later be helpful for the opening repeated chords in Rachmaninov's G minor Prelude Op 23/5, or the triads that begin the last movement of Beethoven's Sonata in C major Op 2/3.

Moving beyond the elbows and returning to a slower tempo, it is fascinating to play each semiquaver from the upper arm, then from the shoulders, the torso… and even from the feet! Once your core is engaged, your feet firmly on the ground and your body relaxed you can focus on channelling all your energies into your fingertips, thereby changing your anatomical perspective as you play. Whether you choose to focus from the knuckles or your upper arms, etc, is entirely your choice. The point is that working in this way gives you a range of choice: having as many options and alternatives for performance is the raison d'être of technical development.

In the next two instalments we shall consider sound and the cultivation of tone and colour. A pianist's range of tone is everything. Debussy's remarkable oeuvre provides particularly inspirational stimulation in this respect as it offers a virtually limitless range of colouristic possibilities.

In colour as in touch, patience and detailed exploration are paramount. Let's close with the reminder that progress in technique will always depend on the degree to which critical self-listening has been developed – which in this context means constant experimentation, refinement and revision of quality of staccato, mezzo staccato, legatissimo and so on. In the practice room we need to think through each phrase mentally in advance, listen critically as we play, then review the outcomes objectively. This threefold process needs to be repeated fearlessly with each musical scrap we work at until progress has been achieved.