Reflections on recording the nocturnes of John Field

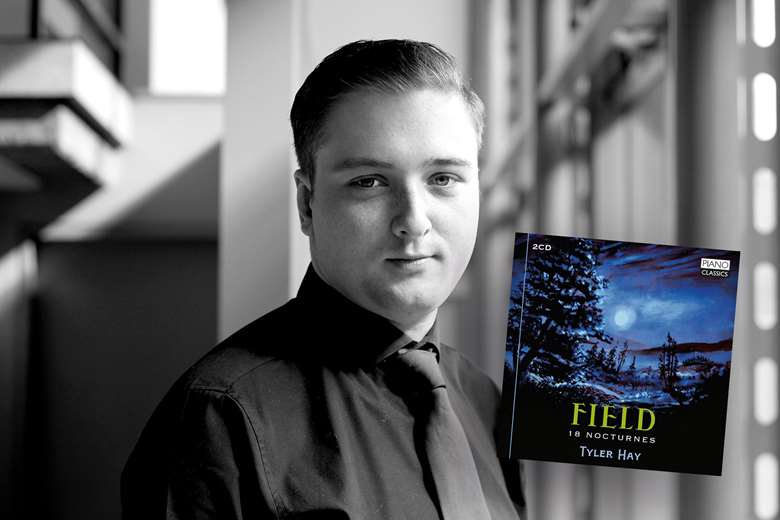

Tyler Hay

Friday, March 8, 2024

Having recorded the complete nocturnes of John Field, Tyler Hay outlines what drew him to the composer and explains the lasting value of his underrated body of work

The nocturnes of John Field have been a very personal love of mine for almost as long as I can remember. I received a life-changing Christmas present when I was eight years old which was a recording of Bart van Oort playing the complete nocturnes of both Chopin and Field. I had already been having piano lessons for two years with my granddad John, but this was an introduction to classical music that touched and inspired me in a way that was completely overwhelming, and I suppose my deep connection with classical music began at this point. I actually became familiar with Field’s nocturnes first and was surprised to learn later that only a couple of them were known within the standard piano repertoire. A while ago, I was chatting with my friend, the pianist Mark Viner, and he told me that this was also the first album that was bought for him as a child and that, ironically, we were now both recording artists for the same company. He also brought to my attention the fact that Alkan knew and admired Field’s nocturnes and often played the C minor Second Nocturne. Shortly afterwards, I was contacted by the very same producer who had recorded Bart van Oort back in the ’90s and was asked if I would like to make a new recording for Brilliant Classics/Piano Classics on a modern instrument. Needless to say, I absolutely jumped at the chance, and after this amazing series of coincidences, I now feel that my musical life so far has come full circle with this fantastic project.

Another huge influence on me was Finchcocks in Goudhurst, Kent. This was a stately home with a truly remarkable collection of early keyboard instruments and historical pianos that was owned by a very fine pianist called Richard Burnett. It was wonderful to see his demonstration recitals and he made quite a few recordings showcasing many of the instruments. Each time my family visited the museum, I would come home with a different CD and so I also became familiar with Richard’s interpretations of several of the Field nocturnes. He died a couple of years ago and the collection had to be dispersed.

A few of Field’s nocturnes have been in my repertoire for many years and I have often programmed them between large-scale works. They are particularly refreshing miniatures and their sparseness and spaciousness are often points of fascination and great beauty for listeners. I have also played Nos 4 and 5 as encores on many occasions. The nocturnes are wonderfully evocative and they exude a special kind of musical fragrance that makes them ideal afterthoughts to a big virtuoso programme.

I find it particularly interesting to learn a complete collection of pieces by one composer for a recording or special concert. First, it’s very interesting to me that the pieces that suit my playing best are not necessarily the ones I would have chosen if I were to formulate a group. To give an example, I decided among other things to learn all of Chopin’s waltzes during the first lockdown and found that they really aren’t pieces I interpret instinctively well at all … except for one: the famous ‘Farewell’ Waltz, Op 69 No 1. If I’d been given the task of selecting four or five to learn for a concert, I wouldn’t have chosen that one. Why is this so often the case? I have no idea! I also think that learning a complete collection gives a musician a special insight into a lot of secrets behind the music. Things like noticing musical links between pieces and discovering a line in the composer’s own journey and development are interesting features and often have an impact on an interpreter’s understanding and concept of the music. So far as Field’s nocturnes are concerned, this is particularly difficult to make sense of as the chronological order of composition is often open to question and there was a period of around 10 years in Field’s life where he composed no music at all. He wasn’t at all careful about cataloguing his own music, which has given editors innumerable problems, dating all the way back to Liszt. Manuscripts of his nocturnes were still being discovered many years after Field’s death in 1837.

It’s an accepted fact these days that John Field invented the nocturne as a musical genre. The question is: why did it come about? We must remember that pianists in the late 18th and early 19th centuries composed much of their piano music to showcase their own pianistic gifts, and in the case of John Field he was particularly adored for his lightness and delicacy of touch. He had been a celebrated pupil of Clementi and so he had been taught in the classical tradition, and even adopted old-fashioned techniques such as the 3-2 3-2 fingering on certain scale patterns to help with this special quality of touch, which was possibly more important to him at times than a true legato. Many composers had written pieces with a nocturnal character but Field’s main concept for the form was to create dreamlike and almost meditative pieces that are full of precious subtlety and gentle charm.

It is inevitable that these pieces are compared with the nocturnes of Chopin but it’s not always wise to do so. Despite one or two moments of greater intensity, Field’s nocturnes are usually still in atmosphere. Chopin admired these pieces enormously but decided that his own concept for the nocturne would explore further into Romanticism and allow for much more emotional turbulence. Put simply, this means that there is more scope for development and artistic freedom, and a genius like Chopin was able to realise this possibility in the most expressive ways. In terms of a comparison of language between Field and Chopin, it must be remembered that John Field was 28 years Chopin’s senior and so was bound to be writing in a more consonant manner. The two composers didn’t always see eye to eye and Field took umbrage to Chopin’s developments of the nocturne: Field claimed that Chopin had ruined his original concept and felt that the younger composer should adopt a different title.

Despite the apparent artistic limitations of Field when compared with Chopin, there are certain numbers that are altogether different in style to any of Chopin’s nocturnes. If listened to with due care and attention, the set of Field’s works can be thoroughly enjoyed in its entirety and each nocturne can be admired for its own uniqueness. Nos 1, 5 and 11 have a delightfully swinging folk element to them that echoes back to Field’s Irish roots. No 3 has an involved and intimate string quartet texture. Nos 4, 8 and 12 are particularly singing in their expressive qualities, with No 8 being the favourite nocturne of Robert Schumann. No 6 has a pastoral touch to it, a feature remarked upon by Liszt. No 7 is especially hypnotic in its repetitiousness and its melodic material is featured in the left hand throughout. Nos 2, 10 and 13 are the only nocturnes in minor keys. The earliest of these three is astoundingly beautiful in its haunting sense of nocturnal mystery, whereas Nos 10 and 13 are laced with deep personal sadness and nostalgia, and have an incredible sparseness that could possibly be compared with a later composer such as Erik Satie. Nos 15 and 16 are very simple and light-hearted in nature. Nos 14 and 17 could be described as ‘fantasy’ nocturnes as they are written on a much larger scale and are freer and more exploratory in terms of structure. Most unusual is the final nocturne, which is ironically called ‘Midi’ – meaning ‘noon’ in French. This is a sunny and sprightly piece that could almost be called a Diurne!

If any direct comparison is to be made with a nocturne by Chopin then it perhaps ought to be Field’s No 9 – a sweet song in E flat major and in 6/8 time that sounds rather like Chopin’s famous Nocturne in the same key, Op 9 No 2. Chopin’s piece contains one of the most gorgeous melodies ever written, but it is worth remembering that when Field wrote his E flat major Nocturne Chopin was only six. I suspect Field’s Nocturne No 9 was a particular inspiration to the Polish prodigy – but whether or not this is correct, it’s clear that Field’s nocturnes have had a considerable influence on so many composers in the last 200 years. It’s been a pleasure and a privilege to study the grass roots of a genre that has remained an integral part of the piano repertoire ever since and continues to remain at the forefront of so many contemporary composers’ minds.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of International Piano. Never miss an issue – subscribe today