Jorge Bolet: an aristocrat of the piano

Donald Manildi

Friday, November 22, 2024

In the final decade of his life Jorge Bolet made a series of recordings for Decca that has at last been reissued in a box-set. Donald Manildi listens to this treasurable collection and summarises the career and legacy of a magisterial pianist

Thirty-four years have elapsed since the death of Jorge Bolet on 16 October 1990. Since then the classical piano world has witnessed an extensive and fascinating series of developments by way of overall performance standards, repertoire expansion and historical awareness of interpretative attitudes. Throughout this period of evolution, Jorge Bolet’s position as one of the foremost figures among 20th-century pianists has remained unchallenged, largely owing to a remarkable recorded legacy that documents playing of unique aristocracy and mastery. A new compilation of Bolet’s final series of recordings for Decca provides an ideal opportunity to re-examine the elements that established his devoted following among connoisseurs of fine pianism.

Born in Cuba in 1914, Bolet arrived in Philadelphia at the age of 12 to begin studies at the Curtis Institute, having already demonstrated precocious natural ability in his native land. At Curtis, Bolet underwent near-militaristic tutelage under David Saperton, son-in-law of Leopold Godowsky. Josef Hofmann, director of the school, also left a strong imprint on the young Bolet, who seized every opportunity to hear the foremost pianists of the day. In later recollections, Bolet consistently mentioned Rachmaninov, Josef Lhevinne, Ignaz Friedman and Benno Moiseiwitsch as inspirational representatives of a tradition to which Bolet, in many respects, became the logical heir.

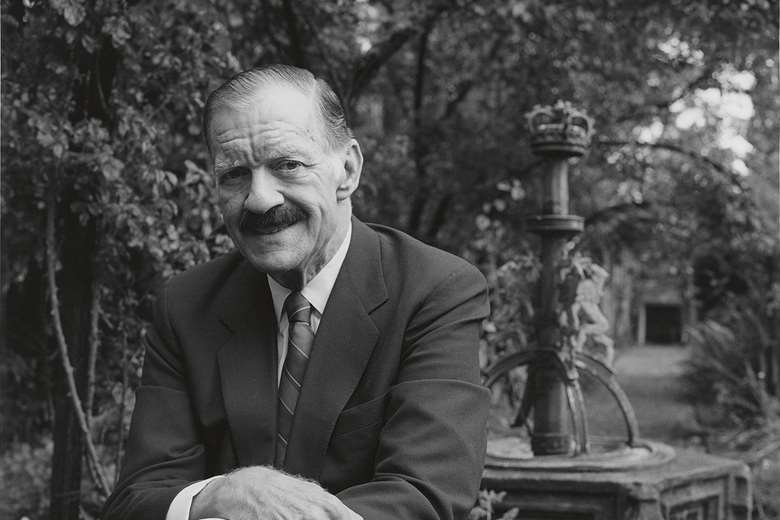

Bolet preferred playing before an audience in concert to the inhibiting environment of the recording studio (Decca Archives)

But because of a combination of unfortunate circumstances, true international recognition did not come to Bolet until the early 1970s. Part of the explanation, as Bolet told it, was a matter of not being heard at the right time by the right people in the right place. Nonetheless, he persevered, steadfastly maintaining his own alpine standards of technique and musicianship. From his earliest performances, Bolet’s complete command of the instrument was unquestioned, and his attributes as an interpreter of a basically Romantic repertoire included superlative tonal opulence and colour, implacable strength and authority, a firm avoidance of flamboyance, exaggeration and mannerism, and a constant search for the poetic essence of every score.

Bolet stands among those pianists – several can easily be named – who reached their ultimate heights only in concert performance. Never comfortable in the recording studio, Bolet frankly stated that ‘recording is the one thing I hate to do more than anything else’. When freed of empty-studio inhibitions and the arduous task of cementing a single performance for posterity, Bolet used the stimulation of an audience to summon his peak level of flexibility and spontaneity. This is evident in the large number of his live performances that have circulated privately, on sources such as YouTube and on certain CD releases (some of which we shall mention shortly). Nonetheless, his extensive series of approved studio recordings still manages to reveal an extraordinary brand of pianism that cannot be ignored.

It was not until 1952 that Bolet made his first commercial LPs. The small Boston label issued a disc of Spanish pieces along with another containing familiar works by Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Liszt. A year later Remington Records, an American budget label, recorded Bolet in the four Chopin Scherzos and in a premiere recording of Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No 2 (a work virtually unknown at the time). The latter carries some truly spectacular playing, despite a regrettable 10-bar cut in the gigantic first-movement cadenza. All four of these early LPs have been reissued on a two-disc set from APR.

In 1958 and 1960 Bolet briefly resumed recording with one-off ventures for RCA Victor (nine of Liszt’s Transcendental Studies) and Everest (standard Liszt and Chopin works). These garnered good reviews but did little to boost Bolet’s visibility with the general public. Another decade passed and Bolet’s appearance as part of a New York benefit concert in 1970 for the International Piano Library created a sensation, so much so that RCA Victor’s interest in Bolet was reawakened with several new all-Liszt recordings. These ultimately led to Bolet’s fabled Carnegie Hall recital of 25 February 1974. This was quickly released in its entirety by RCA and generated long-overdue acknowledgement of Bolet’s true stature among pianists. The gigantic programme combined Chopin’s 24 Preludes, Op 28, with a magisterial sequence of transcriptions: Bach–Busoni, Johann Strauss–Tausig, Johann Strauss–Schulz-Evler and Wagner–Liszt (a titanic, unforgettable Tannhäuser Overture). Bolet himself was later quoted as saying: ‘The only recording I have made that I can view with a certain enjoyment is the live [1974] Carnegie Hall recital.’ This recital is truly an indispensable item; it was reissued as part of a 10-disc RCA Red Seal edition of all of Bolet’s material for that label and for Columbia/Sony; this is now hard to find, although the contents are available for download or streaming. In addition to assorted Liszt repertoire, this set also includes Rachmaninov transcriptions and Bolet’s two collaborations with the Juilliard Quartet (Chausson’s Concert and Franck’s Quintet).

Apropos of Bolet recorded live, there are two productions from the Marston label that represent Bolet at the peak of his powers before an audience, spanning a wide range of years and venues. Both of these must also be considered indispensable and they offer much repertoire that Bolet did not otherwise record. The first volume (two discs) is devoted entirely to Chopin, recorded between 1963 and 1987, including a ravishing B minor Sonata. Volume 2 (six discs) encompasses 50 years (1937-87) of Bolet in concert, meticulously assembled from a vast number of privately recorded sources. One entire disc features original and transcribed works of Godowsky. Further highlights include sonatas by Haydn and Beethoven, large-scale works of Grieg (Ballade), Mendelssohn (Variations sérieuses) and Brahms, and shorter items by Mozart, Rachmaninov and Abram Chasins.

During the 1960s and beyond Bolet was a frequent visitor to Germany. He attracted a substantial following in several German musical centres, especially Berlin, and every year he taped a series of broadcast recordings in the studios of RIAS. Bolet found the atmosphere to be relaxed and congenial, and he offered his radio audience an extensive panorama of repertoire that encompassed numerous works not found on his other recordings. About six years ago, thanks to the enterprise of Ludger Böckenhoff of the Audite label, a remarkable series of CDs drawn from the RIAS archives became available. The importance of these recordings to our perspective on Bolet’s artistry cannot be overestimated. We have seven CDs, divided across three separate volumes. Here Bolet can be heard in his prime, playing both Liszt concertos and Beethoven’s Concerto No 5 (the latter from a concert in Paris); the complete Op 25 Études and four Impromptus of Chopin; Schumann’s F minor Sonata; a wide selection of Chopin and Liszt solos; and the Second Sonata of the American composer Norman Dello Joio (1913-2008; one of the few then-living composers whose music interested Bolet).

The year 1977 was an especially propitious one, for it was then that Bolet embarked upon the series of some two dozen recordings (initially on LP, later on CD) that would document the final phase of his career. He was then in his mid-60s, and Decca producer Peter Wadland, after hearing a London recital by Bolet that offered several Godowsky works, arranged for Bolet to record an all-Godowsky LP for L’Oiseau-Lyre that included eight of his Studies on Chopin’s Études as well as the six Chopin Waltzes that Godowsky transmogrified. The interest generated among pianophiles by this pathbreaking recording led quite naturally to a second Bolet LP for the label, this time devoted to Liszt. Subsequently, all of Bolet’s remaining studio activity was for Decca (the label was called London in the US at this time). We now have the totality of these 1977-89 recordings gathered for the first time in a handsome box-set. With one exception, all were first issued and reviewed individually, although they were not always consistently maintained in the catalogues. This new set embraces 26 discs, which match the contents and follow the chronological sequence of the original releases.

Disc 1 offers the Chopin–Godowsky Études and Waltzes. In 1977 Godowsky’s position among pianist-composers had not yet been properly acknowledged or appreciated. Bolet’s recording was a major landmark in what eventually became a belated renaissance of interest in Godowsky from many pianists. Bolet’s effortless handling of Godowsky’s polyphonic and polyrhythmic textures was revelatory and brought full stature to works that had rarely been given their due – when they were attempted at all. Only occasionally does Bolet miss the spirit of espièglerie that Godowsky implies, but what imposing pianism!

Disc 2 is the second Oiseau-Lyre album, containing Liszt’s five Études de concert plus the Don Juan Fantasy. Bolet’s abhorrence of anything resembling superficial display ensures that Liszt’s ever-imaginative piano-writing comes vividly to life. In Don Juan, other players have dashed through the concluding ‘Champagne’ aria with greater abandon, but Bolet maintains unwavering focus through all 19 minutes of the fantasy and he very effectively rewrites the chordal sequence of the final bars.

No fewer than nine of the discs in this set contain music by Liszt. As one of the great Liszt interpreters of the 20th century, Bolet selected this repertoire with fine discrimination, and it is through his Liszt playing that we encounter Bolet’s finest accomplishments in this collection. His B minor Sonata, for instance, is truly magisterial; Bolet always had the full measure of this masterwork, and his version, after some 40 years, still retains its position as one of the finest accounts on record. Equally authoritative are the first two books of Années de pèlerinage, where Bolet’s multihued tone-painting brings new dimensions to Liszt’s vision and humanity. Also on the highest level are a spellbinding Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude, an epic B minor Ballade and a dozen Schubert–Liszt lieder transcriptions that are as eloquent as they are lyrical.

In three discs devoted to Chopin, we find an exquisite Barcarolle and a superbly proportioned F minor Fantasy sharing space with the four Ballades on one CD, while Bolet’s traversal of the Op 28 Preludes, although admirable, does not carry the sense of occasion evident in his famed 1974 Carnegie Hall account. Bolet views the youthful writing of the two Chopin concertos (with Dutoit/Montreal, 1987) from the autumnal, nostalgic distance of a seasoned observer. In somewhat the same vein are Schumann’s Carnaval and Op 17 Fantasie. The latter’s under-energised second movement is largely compensated for by the ethereal dreamworld that Bolet conjures in the finale.

Bolet as concerto soloist is represented by five standard works in addition to the two of Chopin. His coupling of Tchaikovsky’s First and Rachmaninov’s Second (Dutoit/Montreal, 1987) is largely disappointing. An unmistakable element of reserve prevents either work from catching fire. To only a slightly lesser extent, the same can be said about the Grieg and Schumann concertos (Chailly/RSO Berlin, 1986). Of greater interest is Bolet’s Rachmaninov Third (Iván Fischer/LSO, 1982). Bolet learned the work at the age of 14 and formed, over the years, a carefully considered approach that invests the score with a certain monumentality and grandeur – antipodal to the leaner, more incendiary versions of (among others) Argerich, Wild and Weissenberg.

Special mention should be made of two massive, seldom-performed sets of variations in which Bolet meets and conquers their challenges head-on. He was a staunch advocate for Max Reger’s Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Telemann, and we are fortunate to have his near-definitive account, recorded in Kingsway Hall in 1980. He builds the huge structure inexorably to a mountainous conclusion. No less impressive are the Variations on a Theme of Chopin by Rachmaninov (recorded in 1986). Bolet clearly believes in this imposing work and relishes the pianistic elements while skilfully preserving continuity. (The Reger is coupled with an excellent account of Brahms’s Handel Variations, while the Rachmaninov album offers a selection of the Russian’s shorter pieces.)

An unarguable highlight of Bolet’s Decca series is the collection of 18 encore pieces recorded in December 1985. Seven short, familiar Chopin works are included along with five by Godowsky. We are also given two Bolet specialities that never failed to bring down the house: La jongleuse by Moszkowski and the Étude in A flat by Paul de Schlözer (made famous by Eileen Joyce’s 1933 debut disc for Parlophone). Bolet’s incomparable sense of style makes this album a true feast of resourceful pianism.

On occasion Bolet would venture into Schubert’s sonatas (including, in his younger days, the perennial B flat major, D960 – of which we seem not to have a surviving performance by him). For his only Decca recording of the composer, set down in 1989, Bolet chose the posthumous A major, D959, and the three-movement A minor, D784. There is an ‘elder statesman’ aspect to his approach here, notably in the Scherzo of the former and the Allegro vivace finale of the latter; both would have benefited from less conservative tempos. Still, Bolet holds the big A major work together through firm rhythmic discipline and his persuasive shaping of the melodic material. Rather severe Schubert playing, to be sure, but not without its own interest.

The music of Debussy did not appear with great frequency in Bolet’s recitals – usually just a small selection from the two books of Préludes. For sessions in San Francisco in September 1988, Bolet selected 16 Préludes, arranged in a sequence emphasising their wide variety of contrasts. Here, an element of excessive sobriety makes such pieces as ‘Minstrels’, ‘La danse de Puck’ and ‘Général Lavine’ less than successful. On the other hand, Bolet captures the bleak atmosphere of ‘Des pas sur la neige’ in ideal fashion, and he dispatches ‘Feux d’artifice’ with stunning brilliance.

An outlier within this collection is disc 24, containing excerpts from an April 1988 recital in Alabama. Bolet’s powerful, grandiose Liszt Réminiscences de Norma (after Bellini) is preceded by Franck’s Prelude, Chorale and Fugue. (The latter is also part of disc 21 in a studio version from two months earlier, alongside the Prelude, Aria and Finale.) Bolet always presented these triptychs with total command and a thorough identification with Franck’s idiom.

Included as disc 26 is a CD of previously unreleased performances that stem from Bolet’s final recording sessions in San Francisco (February 1990). There are seven Chopin Nocturnes and the Berceuse; they require special comment. It is unclear whether Bolet approved these performances for release. He was not in good health at the time (he underwent brain surgery a short time afterwards) and the playing throughout is leisurely in the extreme. This ruminative quality imparts an unmistakably valedictory air to the proceedings, and despite the abundant surface beauty we sense that Bolet was not fully engaged. Moreover, the disc is plagued with an assortment of sonic problems as the result of what is obviously a cassette source transferred with noise-reduction mis-tracking. There are recurring tiny dropouts and other anomalies in the piano image, which lacks the characteristic refinement of Bolet’s other solo recordings. In addition, the pitch is slightly flat throughout. It would have been preferable to search for the original source material and prepare a clean remastering. Instead we have a regrettable missed opportunity.

However, it would be wrong to conclude on a negative note. We would be much the poorer if Decca had not been strongly committed to capturing Bolet’s late years so comprehensively. When we survey the playing preserved in this new set, along with the best examples from Bolet’s concert and recital performances (see the panel opposite), we can obtain a just perspective of how he achieved his position among the greatest 20th-century pianists. With the one exception noted, the set’s production values are on a high level. The accompanying booklet contains a superb appreciation of Bolet’s career by Jonathan Summers as well as numerous photographs.

Jorge Bolet: Complete Decca Recordings

Decca 485 4283

(26 CDs)