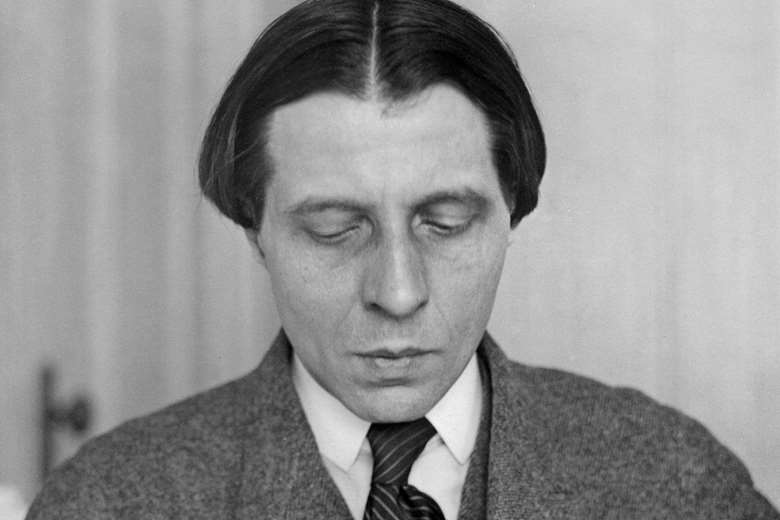

Historical Perspectives: Alfred Cortot

Mark Ainley

Friday, November 22, 2024

Mark Ainley salutes the all-encompassing pianism and creative imagination of Alfred Cortot, whose recordings – tracing a period of rapid technological development – continue to engage and inspire

Recording technology is miraculous for its ability to preserve great musicians’ artistry but the medium is not without its limitations. Concerts were for centuries unique occasions never to be repeated, but the permanence of studio recordings crafted in conditions radically different from live settings can freeze a performance for eternity, and repeated listening can invite misguided scrutiny.

Among the most prolific recording artists of his generation, his playing both routinely revered and unduly dismissed, was the great French pianist Alfred Cortot, whose teachers included Chopin’s pupil Émile Decombes. Cortot’s solo discography, spanning about 40 years, comprises dozens of hours of inspired pianism eminently worth exploring. His individual style also raises important considerations about both the value and the limitations of recordings, and about musical interpretation itself.

Cortot’s legendary interpretations are all the more remarkable when one considers the conditions under which they were produced

It is sadly common for present-day listeners to disparage Cortot on the basis of a single aspect of his recordings: wrong notes. In the first decades of recording technology, no editing was possible because performances were etched directly into the grooves of the master disc. Musicians therefore had to play entire sections – four to five minutes on a 12-inch 78rpm record – with no possibility of small corrections; if they dropped some notes, they either made another attempt or released the performance ‘as is’.

It might be hard today to imagine why an artist would leave a mistake in a recording, but there are several factors to consider. Recordings were not always seen as permanent statements of an ideal interpretation, nor were they meant to replace concerts, which were occasions when listeners (back then, at least) were accustomed to occasional flubs occurring in the heat of the moment. Most musicians also did not likely anticipate their recordings being available (and scrutinised) a century later.

We should also consider the circumstances of the artist’s life. Cortot was not just a solo pianist and chamber musician, he was also a conductor as well as a prolific editor, writer and teacher (he taught some of the greatest pianists of the 20th century). With such varied undertakings, he simply did not devote the time to consistent practice that his performance-focused colleagues did. A mere glance at his guidebook to piano exercises, Principes rationnels de la technique pianistique, and the exercises in his editions of Chopin and Liszt – which were praised by Horowitz – indicates an astounding mastery of keyboard mechanics.

A broader question is what ‘technique’ involves. The word is usually equated with accuracy and velocity, but great pianism also encompasses tonal palette, dynamic control, phrasing, articulation, pedalling, voicing and other means of bringing music to life. We do not praise an actor for simply reciting their lines. Do precision and speed alone equal ‘technique’? Cortot’s priorities are clear: he once noted about a student’s performance, ‘This music contains within it all the passion of a first love, and you have reduced it to a marriage of convenience.’

These considerations might suggest that precision was wholly absent from Cortot’s playing but this is far from the truth: his early recordings in particular demonstrate stunning virtuosity. His 1919 account of Saint-Saëns’s Étude en forme de valse is so fleet and dazzling that a young Vladimir Horowitz went to Paris to study with Cortot just to learn how he navigated the work; unimpressed by this superficial motivation, Cortot refused to show him. (In the 1930s, however, Cortot coached the then-famous Horowitz on more musical matters, hosted him at dinners and conducted his Paris performances of the Emperor and Rachmaninov Third concertos.)

The true grandeur of Cortot’s music-making lies in less tangible dimensions. Few pianists brought scores to life with such creativity and imagination – the most extraordinary qualities in Cortot’s musical skill-set. His Chopin Études are thrilling beyond displays of dexterity, with daring tempos, drive and momentum, magical tonal colours and sublime voicing. Just as these works are not mere technical studies but rather musical masterpieces, Cortot plays them with multifaceted technique, relishing details with attentive nuancing while serving the big picture. If a few notes get dropped in the process, as Harold C Schonberg noted in his celebrated tome The Great Pianists, one accepts this ‘as one accepts scars or defects in a painting by an old master’.

Cortot’s legendary interpretations are all the more remarkable when one considers the conditions under which they were produced. In just five days – 4-8 July 1933 – Cortot set down Chopin’s Second and Third Sonatas, four Ballades, four Impromptus, the Op 10 Études and Op 28 Preludes, F minor Fantaisie, Tarantelle and A flat major Polonaise. That he delivered such magnificent performances in a studio with no audience while the clock was ticking with the expectation of producing commercially viable discs is almost inconceivable.

Cortot recorded a wide array of solo works from arrangements of Bach and Purcell through the Romantic era to Franck, Albéniz, Debussy and Ravel, his primary focus being Chopin and Schumann. His soaring phrasing, sumptuous colours, evocative pedal effects, graceful timing and distinctively rich, ‘aromatic’ timbre were ever-present even as his playing evolved over his 35-plus-year recording career. Although his precision waned as he aged, there was a reciprocal increase in tonal depth and creativity, his readings becoming ever more hypnotic. His entire discography offers an abundance of riches that can deeply enhance an appreciation of what is possible at the piano.

Cortot’s first decade in the studio, beginning in January 1919 (when he was 41), finds him at his most consistently virtuosic, his readings featuring crystal-clear articulation and stunning evenness of fingerwork, dispatched with panache and bravura: prime examples include Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies Nos 2 and 11, La leggierezza and Rigoletto paraphrase (after Verdi), and Handel’s The Harmonious Blacksmith. His poetic nature was already in evidence, and his Fauré Berceuse is particularly mesmerising for its rhythmic lilt, soaring line and poised voicing.

Cortot’s playing remained bold and adventurous even as lapses in precision started to become more noticeable in the late 1920s and 1930s, but the nobility and poise of his approach became even more evident, as did his sense of fantasy. His Chopin Third Impromptu has such creative timing and effervescent phrasing that others sound square in comparison, and he produced other-worldly accounts of many Schumann works, his quixotic Davidsbündlertänze and Kreisleriana being particularly alluring. His last pre-war London sessions in 1939 produced some beguiling Chopin-Liszt songs and a Weber Piano Sonata No 2 that is overflowing with charm and elegance; unfortunately the Gaspard de la nuit from the same session was marred by a material fault and no pressings have surfaced.

Wartime recordings in France feature remakes of Chopin’s Études, Waltzes and Preludes that did not circulate widely but that find Cortot, in his mid-60s, still playing with impressive intensity and bravura; sadly, his takes of the Scherzos and Polonaises were not published and are lost. By the time he resumed recording in London in 1947, his playing had become more expansive, and improved engineering faithfully captured his distinctive tonal palette and impressionistic pedalling. He re-recorded works by Schumann, Chopin and Debussy that he had set down in preceding decades, achieving even more atmosphere and tonal richness. A 1954 Largo from Chopin’s B minor Sonata is among the best of his late readings, one of the most heartfelt accounts of this movement on record.

Cortot recorded only five concertos, his 1935 reading of Saint-Saëns’s Fourth Concerto showcasing his refined pianism and vivacious momentum to perfection. While multiple versions exist of Cortot playing Schumann’s Concerto, he never recorded many concertos that he performed publicly, including complete cycles of Beethoven and Saint-Saëns and Rachmaninov’s Third. The sole live concerto recording outside the repertoire he set down in the studio is a stellar 1947 Beethoven First Concerto, leaving one to lament that Cortot made no official recordings of this composer’s solo and concerted works when he was in his prime.

There are some 1950s radio broadcasts (some with applause added) but no actual recital recordings – a shame, since Cortot seems to have been at his best playing live. There are magical glimmers in a three-disc set produced by Murray Perahia culled from recordings of 1950s masterclasses: some of his demonstrations suggest that even his best studio playing might have been a shadow of his true abilities. Excerpts of Bach’s First Partita and late Beethoven include some of the most inspiring, transcendent pianism ever recorded. By the time he recorded the complete Beethoven sonatas in the late 1950s, his capacity had so diminished that they were not published; some movements are now available, offering insight despite their limitations.

Our external-metric-focused society can be quick to dismiss on the basis of superficial criteria. As with the adage to look at the moon and not at the finger pointing at it, listeners would do well to focus not on Cortot’s fingers but instead to gaze beyond the moon into the cosmos beyond that his enthralling pianism evokes. Listening to Cortot you are not merely hearing music or even a performance: you are bearing witness to the creative expression of a profound poetic spirit, one unique in musical history.