Recording focus: Marc-André Hamelin on Fauré's Nocturnes and Barcarolles

Harriet Smith

Tuesday, September 26, 2023

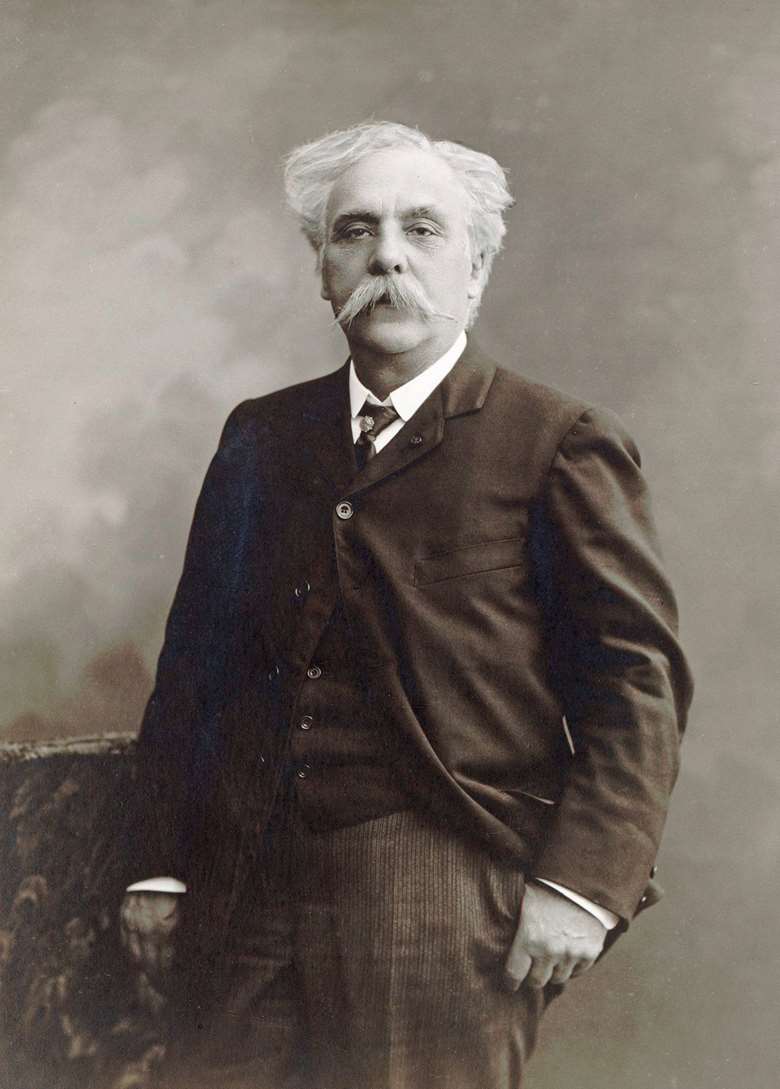

Marc-André Hamelin is well known for his omnivorous appetite for the highways and byways of the piano’s repertoire. He talks to Harriet Smith about exploring the refined subtleties of a fin de siècle French composer

Register now to continue reading

This article is from International Piano. Register today to enjoy our dedicated coverage of the piano world, including:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to International Piano's news pages

- Monthly newsletter