Wilhelm Furtwängler: The Man and Myth

Gramophone

Wednesday, March 1, 2017

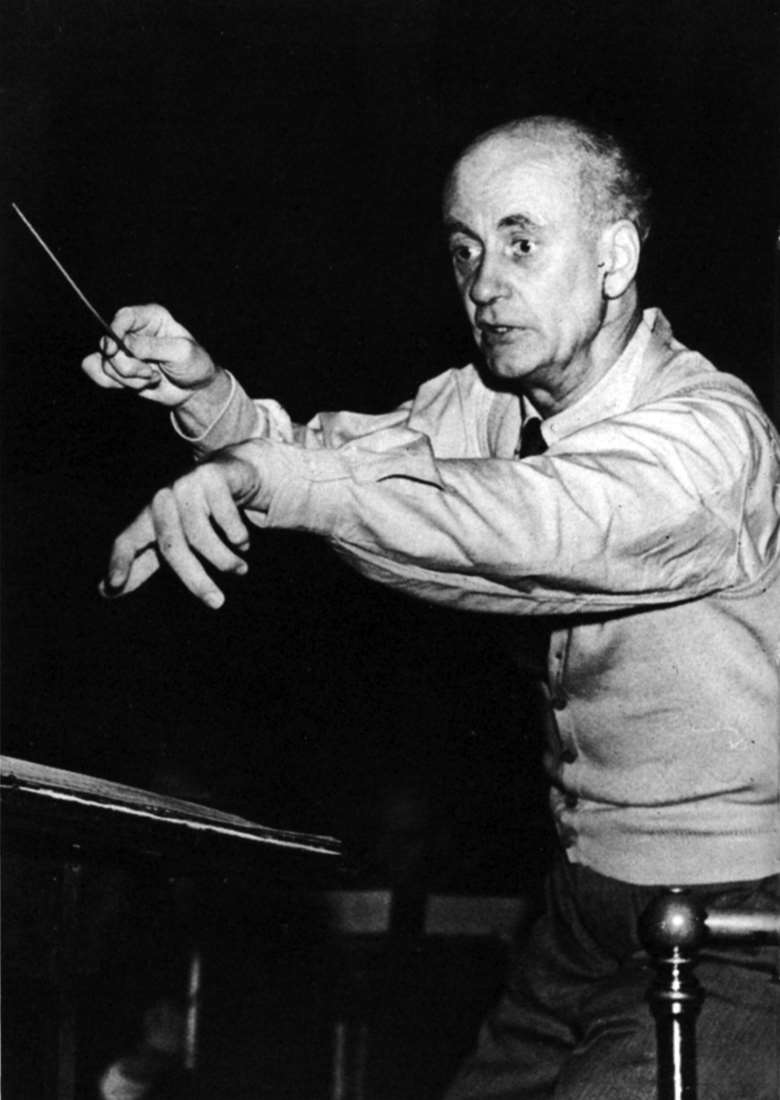

Rob Cowan reflects on the triumphs and controversies of one of the greatest conductors of all

You could say that although the great German conductor-composer Wilhelm Furtwängler passed from our midst more than 50 years ago he still refuses to die. Furtwängler remains powerfully relevant, a symbol of numerous key crises that continue to nag at us, not least the aspiring composer forced to recreate the work of others and a creative free spirit ensnared by the political vices of his age. Repeatedly forced to test his integrity in a world that was at painful odds with his principles, Furtwängler was naïve, vain, fatherly, occasionally high-handed and unstintingly devoted to his art, the ultimate case of an interpreter with a vision whose powerful re-creative instincts re-moulded the music he played. And while his great arch-rival Arturo Toscanini remains a revered historical figure whose light is beginning to flicker, Furtwängler continues to excite debate, controversy and influence.

By saying that I don’t mean either to decry or devalue Toscanini’s colossal contribution to the art of conducting, more to underline Furtwängler’s uniqueness, which was both artistic and circumstantial. His records are valuable not only for what they tell us about a very personal vision, but for a whole future family of visions cast along parallel lines. Indeed, every musician who smacks at the face of fad or fashion stands to learn from Wilhelm Furtwängler’s example.

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Martin Wilhelm Furtwängler, the only musician in his family, was born in 1886, the same year as Edwin Fischer and Arthur Rubinstein, and the year that Franz Liszt died. His mother Adelheid was a painter and his father Adolf a leading classical archaeologist. Young Wilhelm benefitted from being born into a cultivated humanist environment, from a private education (principally by an archaeologist, a sculptor and an art historian), the opportunity to accompany his father on excavations and from early trips to Italy and Greece. These and related activities inspired a lasting appreciation of the personalities and principles in ancient Greek history as well as a love of Shakespeare, Goethe and other major writers and thinkers. Hence the palpable sense of awe that was at the very heart of Furtwängler’s greatest interpretations.

Blessed with an outsize imagination and a prodigious memory Furtwängler soon gravitated to music, and by the time he was 17 had written numerous works including a symphony and settings of Goethe. Composing would remain a vital function throughout his life. He always thought of himself as a composer first and foremost, and the attention that musicians such as Barenboim and Sawallisch have lavished on Furtwängler’s Brucknerian muse will surely earn it a well-deserved posthumous credibility. It was largely through a desire to conduct his own music that Furtwängler adopted his chosen profession, that as well as a burning love of Beethoven, an increased interest in the art of interpretation and the need to support his mother after his father’s death. His first concert (with the Kaim Orchestra) was in 1906 and included, in addition to the Ninth Symphony of Bruckner (another abiding love), his own Largo in B minor, later reworked into his First Symphony. So it is easy to see how Furtwängler’s elevated view of art was nourished by fertile early training. He was steeped in high culture and subsequent studies with the great Austrian music theorist Heinrich Schenker helped mould and focus creative and re-creative instincts that were already being set to good use. Schenker enabled Furtwängler to understand the harmonic structure of music, the significance of (for example) the tensely held dominant seventh that takes us from the end of the Scherzo to the beginning of the finale in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. True, any half-decent performance will make that same point, but the heady combination of Furtwängler’s intuition and Schenker’s powers of analysis meant that in addition to merely hearing the transition we begin to realise its full rhetorical import, the humbling shock of the musical moment.

Critical responses to Furtwängler’s conducting have traditionally pitted his ‘subjective’ (Dionysian) approach against the more ‘objective’ (Apollonian) style of his older contemporary Toscanini, someone who prided himself on truthfulness to the score in the face of wilful, ego-centred colleagues — who no doubt included Furtwängler, at least on occasion. At this point it is worth recalling a recent interview with Daniel Barenboim who, in comparing these two rostrum giants, made the interesting point that while in youth the privileged Furtwängler was able to work with good orchestras, the under-privileged Toscanini had the unenviable task of drilling under-par provincial players. So while precision and tight ensemble became life-long preoccupations with Toscanini, Furtwängler had the luxury of setting his sights elsewhere. Furtwängler’s Notebooks (Quartet Books: 1989) include an extraordinary entry on ‘Toscanini in Germany’ where, in the context of reporting on Toscanini’s Beethoven, he cites a passage where ‘the functional meaning of the modulations in the long term, which in absolute music such as Beethoven’s play such a different role, seem to be completely unknown to Toscanini’s naïve feeling for opera music’. This candid confession seems to me to encapsulate a crucial difference between the two conductors — later terms in the same entry include ‘Beethovenian attitude’ and ‘tensed stillness’ — where Furtwängler’s intuition is aligned with authentic expression and Toscanini’s manner more with immaculate execution and technique. And yet while Toscanini was widely lionised as a unique phenomenon, a sort of musical cleansing agent if you will, Furtwängler’s more individualistic approach attracted equal levels of adoration. However, working visits to New York in the mid-1920s attracted both praise and derision and although in 1936 Furtwängler was subsequently invited to become Toscanini’s successor as head of the New York Philharmonic, local protests made him withdraw, and John Barbirolli took up the post instead.

Dark days lay ahead. Much ink has been spilt attempting either to analyse or explain Furtwängler’s complex attitudes during the frightful years of Nazi rule. Even now, in the 21st century, it is almost impossible to gauge how this creatively motivated, idealistic, stubborn and loyal individual must have felt when faced with the Party’s wily propaganda and brute enforcement of laws that were both unfair and unjustified. At the time Furtwängler was into his second decade as chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic while working closely with the Vienna Philharmonic and touring abroad, including London, where he conducted at Covent Garden and at the Queen’s Hall.

In 1934 when Hindemith’s opera Mathis der Maler was banned, Furtwängler resigned all his official posts. Subsequent brushes and compromises (including a more-or-less enforced performance of Beethoven’s Choral on the eve of Hitler’s birthday) were balanced by the support he offered Jewish musicians and the hope he gave the many upstanding Germans whose personal worlds were in tatters. ‘I stayed to save what I could’ is, in the briefest of terms, what Furtwängler ultimately decided to do, but he paid a heavy price.

Post-war hostility, especially from America, and the necessary indignity of de-Nazification took its toll and although Furtwängler’s eventual post-war career was extremely busy, incorporating as it did Italian performances of Wagner’s Ring, recordings and countless concerts, the die was cast. By the autumn of 1954 a combination of exhaustion and encroaching deafness challenged his will to live. With heroic fortitude Wilhelm Furtwängler confronted the inevitable and died peacefully at a Baden-Baden clinic with his wife by his side. He was 68.

Many of those who knew and worked with Furtwängler idolised or at the very least greatly admired him. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf tells how he was always concerned to keep as fit as possible, observing a strict regime of diet and exercise. He loved nature, walks, swimming and skiing. In addition to taking the greatest pains over the music he conducted or played (he was also a very capable pianist), he cared about his musicians as individuals. Schwarzkopf relates his tactful advice to her when, as she told me, it seemed as if her days as a ‘Choral Symphony soprano’ were drawing to a close, that her voice was changing and that she should prepare to face fresh challenges. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau recalled how Furtwängler would ‘father’ him, want to meet his wife, inquire about his health – all manner of important but in the ‘normal’ professional run of things irrelevant issues. When he died his orchestral players were devastated, some of them even going as far as to threaten to abandon the music profession altogether. Their leading light had been snuffed out; Furtwängler was their inspiration, a trusty guide who could draw them into a elevated world that could barely exist without him.

Post-war reparations included the reinstatement of ‘verboten’ music such as Mendelssohn, Hindemith and Mahler. Earlier in his career Furtwängler had conducted Mahler’s Third Symphony, but as Fischer-Dieskau told me, he was no Mahler fan. Furtwängler thought that Mahler’s First Symphony lost its way after the first three movements, though he did eventually gravitate to the Lieder eines fahrenden gesellen (which he recorded with Fischer-Dieskau) and to the Kindertotenlieder, which they performed together but never recorded. Even the most cursory glance through Furtwängler’s concert listing reveals many appetising surprises, not least Vaughan Williams’s Tallis Fantasia, Reger’s Böcklin Portraits, Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. But the recordings we do have, most of them live, give a generous picture of the many qualities that made his artistry so special.

How then can we best define that unique artistry? Taking it from the top (so to speak), a Furtwängler performance didn’t so much start as emerge. That famously indecisive beat was a ploy with a purpose and not, as some professional musicians will tell you, a symptom of technical incompetence. Listen for example to the opening of Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge (DG), which Furtwängler performs in a full-strings arrangement. True, the initial chord is uneven, but the lack of unanimity is intentional, a rugged ‘growl’ as opposed to a bloodless ‘snap’. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is another case in point, the opening four-note motto invariably shaggy and a little unkempt, but tightening later alongside the argument.

Furtwängler’s choices of tempo and dynamic were less dictated by strict textual observance than following a harmonic road map based loosely on Schenkerian principles, that low-crouching transition into the finale of Beethoven’s Fifth being an especially good example. Another is the artful shaping of Bach’s ‘Air’ (Suite No 3). Or, even better perhaps, Furtwängler’s leisurely but extraordinarily intense piano playing in the first movement cadenza of Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg Concerto, a crumbly old recording from the 1950 Salzburg Festival but a supremely effective example of how targeted expression can transcend issues of period style.

Years ago, before live radio recordings were as readily available as they are now, commentators with poor memories would have had us believe that each Furtwängler interpretation of a particular piece differed from the last. Not so, as a systematic journey through the dozen available Beethoven Fifths will easily confirm. Yes, the temperature, mood, or level of emphasis might change but in general the overall shape of the interpretation never did. Take the closing prestissimo of Beethoven’s Ninth, a manic onslaught whether in London in 1937, or in Bayreuth or Vienna in 1951 or even in front of Hitler in 1942. The ground plan had been set and was not to be challenged. Paradoxically it was Toscanini, so often daubed as the ultimate strict-tempo band-master, who was the more likely to introduce minute changes between performances. For proof, lend an attentive ear to the first movement of Beethoven’s Ninth in the live NBC recordings from 1938 (Music & Arts) and 1939 (Naxos).

I am convinced that posterity will favour Furtwängler’s live legacy over his studio recordings. Of course there are notable exceptions. Schumann’s Fourth Symphony was set down more or less in a single take after Furtwängler had become so exasperated by the stop-and-start recording process that he would have walked out otherwise. Which is why Schumann No 4 provides one of the precious few instances where there is nothing to choose between the studio recording and (in this particular case) the one extant live recording that we have, save that the studio sound is infinitely better. The reason being that the commercial session was in all essentials ‘live’.

Hans Keller famously labelled Furtwängler as being ‘the opposite of a gramophone record’ and it is a matter of some regret that it was only towards the very end of his life that Furtwängler finally realised how recording could, given the right producer and environment, actually work artistically. Recording the famous 1951 EMI Tristan und Isolde was a pivotal experience, much of it achieved in fairly long takes and, according to both Fischer-Dieskau and the Philharmonia’s lead flautist at the time, Gareth Morris, without much in the way of either stress or tension. Others have reported how Furtwängler would occasionally allow his temper to flare, maybe to increase tension during the sessions.

In general though there are few studio recordings that genuinely ‘light up’ in quite that way. The real Furtwängler resides in those many broadcasts that have been appearing at regular intervals ever since the tenth anniversary of the conductor’s death back in 1964 (though by now the flood of genuinely ‘new’ material seems to have more or less dried). The difference between Furtwängler in the studio and Furtwängler live is like the difference between lip service and sincere communication. In concert he initiated a communal ‘happening’, unleashing forces that would storm from the stage and overwhelm his audiences. I’m thinking of the opening of Brahms’s Third Symphony (BPO, 1949), which launches on a crescendo from the brass then takes fire among the strings. You can almost feel the heat and yet there is no brass crescendo marked in the score. That is the invariable dichotomy with Furtwängler, the conflict between stave and stage, between the repressed maid of the written score and the liberated princess in flight with her prince. Furtwängler as prince had that uncanny ability to lift the notes off the page in a way that would have made the great composers both despair at the limitations of the pen and shout for joy at the insights of a like-minded interpreter. But then there are some things that only a composer knows, and Wilhelm Furtwängler was that, too.