What exactly is a beautiful sound?

Philip Clark

Friday, March 20, 2015

Bob Dylan’s defence of his own singing voice raises questions about the perception of beauty in music that composers and musicians can’t afford to ignore

Bob Dylan turns up at the MusiCares Person of The Year Awards in Los Angeles, where he is due to be honoured, with a 30-minute homily tucked inside his jacket pocket. Musicians and industry honchos who have aided and abetted his career and generally inspired him are cordially acknowledged – then he uses the opportunity to settle some long festering personal grievances.

‘Critics say I can’t carry a tune and I talk my way through a song,’ the 73-year-old folk warrior snarls, before drawing some serious blood. What justice in a world where he, Bob Dylan, must endure regular critical slap downs for a voice that apparently sits at the very point of disintegration, with shaky diction and lucky dip tuning, when throwing comparable critical missiles in the direction of Lou Reed or Dr John would be unthinkable? ‘You have to wonder if these critics have ever heard Charley Patton or Son House or Howlin’ Wolf,’ Dylan adds as a rider, invoking the ghosts of some long-departed delta blues singers to back his cause.

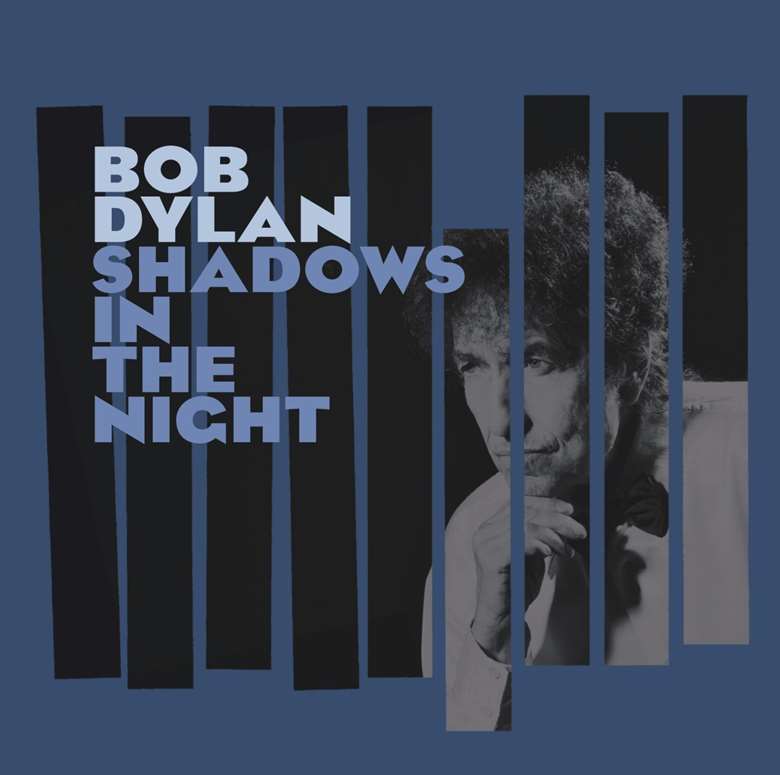

And within minutes of those words leaving Dylan’s mouth earlier last month, the anti-Dylan naysayers were quick to pounce. From his position of unassailable power within what is left of big business, major label music, Dylan had managed to twist what ought to have been a celebration into a needlessly bitter, bad-mouthing occasion. With his new album to push, was he on a mission to generate headlines? Probably. Especially as said new album, Shadows In The Night, is his homage to Frank Sinatra, an improbable prospect in the extreme likely to reveal, if anything would, how rough and ready Dylan’s voice is in comparison to Sinatra’s cannily choreographed crooner velvet: being in tune a virtue next to godliness, each note immaculately enunciated.

In reality, though, Shadows In The Night is all about Dylan’s genius for transforming any song he chooses to snare into a meaningful, distinctive personal vehicle. And while it’s true, the section of his speech I quote above is surprisingly clumsy – sorry, Bob, but it is – the reason why nobody is minded to say much against Lou Reed is that he died two years ago; and a swanky Tinseltown ceremony might not be the best place to claim allegiance with some of the most disadvantaged people ever to have committed their voices to disc – Dylan has every right to feel seriously aggrieved about those unthinking, sneering words about the supposed deficiencies of his voice that regularly fill the column inches.

His speech dispensed a stark, barbed repudiation of a critical position that, over many years, has solidified into a self-perpetuating ‘truth’. The idea that Dylan’s voice is unpalatable to the ear has become a crude caricature, up there with the popular mythology surrounding Roger Moore acting, supposedly, via the expressive muscle of a quizzically raised eyebrow – on a good day eyebrows. But Roger we love you. Carrying off the pristine white of a Safari suit takes more than an innuendo-laden face tic. And dismissing the Dylan of the last two decades or so simply because he doesn’t sound now like he did during his mid-1960s flush of youth is equally reductionist and judgemental.

But what has Dylan’s acceptance speech, his new album and the peculiarities of his singing voice got to do with Gramophone-world? Typified by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau or Janet Baker, you may feel that his work has precisely nothing to do with vocal utterance as this magazine understands it, but I would like to propose that Dylan’s address ought to make anybody who considers themselves to be a lover of music, and therefore sound, stop and think. Knowingly or otherwise, Dylan is rekindling an argument with deep philosophical roots in Kant, Hegel and Schopenhauer. What exactly is a beautiful sound? And who are you to say that your sense of what is – and therefore isn’t – beautiful holds greater weight and certainty than the equally passionately held conviction of anybody else? Dylan’s words oxygenate an argument that is often nonchalantly swept aside. Classical music buffs know instinctively what beauty is, because, well it’s obvious…isn’t it?

I have written before – too often probably – about the German composer Helmut Lachenmann and his philosophy of the beautiful, but quite honestly I live for mornings like this when I can segue seamlessly between Bob Dylan and Helmut Lachenmann via Roger Moore. ‘It’s very easy to write so-called “expressive” music using old patterns,’ Lachenmann once told me. And the ideal of the beautiful he proposes holds in distain faux-convincing ‘beautiful sounds’ that work only at the level of cosmetic decoration.

During our 2002 interview, he drew a comparison between two visual extremes: manufactured, airbrushed photographs of Madonna and images of Marlene Dietrich taken during her twilight years. The market would like us to buy (literally) into the idea that Madonna’s sexualised curves and flawless skin is ‘beautiful’. Sex sells and beauty, apparently, equates to physical perfection. But the persona of Madonna (as distinct from Louise Ciccone) is a product and such photographs are revealed to be an infantile illusion. Whereas the honest wrinkles and dignity of Marlene Dietrich have a beauty that is unaffected and therefore undeniable.

As a rule of thumb, art has a duty – although not necessarily – to offer more than unmediated sound and image. Lachenmann drew an analogy between his (then young) daughter and JS Bach: ‘If I want to understand what’s going on in the mind of my little daughter,’ he said, ‘better for me to observe how she writes a letter or how she sits on a chair than to ask her. If I ask, she has to find vocabulary to articulate or even hide her thoughts and feelings; but by observing I can see immediately what’s going on inside her mind.’ Lachenmann explained that in his Inventions, Bach manipulates motifs built around five fingers, asking us to observe how ‘(through) his creative intelligence and effort the work is a message of human spirit and freedom.’

The point being, I think, that beauty invariably comes loaded with terms-and-conditions. One stricture that British so-called ‘light music’ (the work of Eric Coates, Ronald Binge, etc) shares with the neo-Modernism of a Richard Barrett or Rebecca Saunders is that a pre-compositional decision has already been taken that this music, whether it wants to or not, must exhibit Category A ‘lightness’ or create a designer ‘modern’ sound – which means musical material must be tailored to fit an existing idea of what it ought to be. Leeway for that material to be itself, to occupy comfortably its own skin, or to discover during the act of creation what it might aspire to be, is severely curtailed.

But this philosophical backchat would mean little if nothing were to change in sound. A straw pole that posed the question ‘what is a beautiful musical sound?’ would likely throw up a smorgasbord of musical bon-bons from Delibes’s Flower Duet and a selective view of Mozart and Beethoven (the Moonlight Sonata, yes, the Hammerklavier less likely) through to Hit Parade ditties by Chris De Burgh and James Blunt, leaving those of who genuinely get our jollies from the bracing sublimity of Lachenmann, Ustvolskaya, Xenakis, David Tudor, or the free jazz of John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor, to wonder why we have been left out of this particular beauty pageant.

Music has nothing to fear from sound. The sonic firepower of orchestras, choirs, nimble-fingered instrumentalists, and the theoretically limitless resources of electronics, ought to leave our ears begging for more. But the protectionist culture that surrounds classical music – if not the music itself – places squeamish barriers around sound. Beauty being synonymous with smooth delivery; with mathematically pure symmetry; with harmony that resolves rather than leaves itself hanging, is hard-wired inside impressionable brains from those very first music lessons when, to execute a flawless C major scale, we are taught that the thumb must be tucked under the third finger in time to reach the F. Beauty leans on technique; the exquisitely proportioned melodic line of the Flower Duet relies on two singers who are unerringly in tune; the Moonlight Sonata’s opening movement must flow like ripples across a pond.

And assuming those ripples don’t splash over into interpretive mannerism, there is of course absolutely nothing wrong with allying music to the appropriate technique. But when composers are minded to start rearranging the basic molecules of technique – hinting that other definitions of the beautiful might be possible too – that is where problems of perception can begin.

Lachenmann’s wholescale deconstruction of conventional technique begins from asking more complicated versions of questions like what would happen if the fourth finger was tucked under the thumb; at the moment the third finger wasn’t being used, what would this counterintuitive finger position do to the quality of sound? In her sequence of six piano sonatas, Ustvolskaya rebooted the Russian piano tradition by entombing triadic patterns inside driven, whacked clusters, the relentless physicality of the music requiring a rethink of how to angle and position the hand. And perhaps the most striking abandonment of traditional technique is the case of David Tudor who, after using his immaculate piano technique to serve the notey fancies of Boulez, Cage and Stockhausen, gave up on the piano and instead began to assemble compositions of his own which deployed electronic circuits designed precisely so that he could not fully control their urges to bleed into each other; the electronics taking over where technical certainty tailed off. Put your fingers here, you’ll hear this sound. Conventional technique guarantees that absolute assurance. But these composers prefer to work with technique as a sliding scale of potentialities – finding beauty in all the cracks.

Which brings us back to Bob Dylan. Critical tussles about his recent work turn around questions like why the lispy but controlled voice that in 1964 gave us this –

- has apparently collapsed, 50 years later, into something croaky and strained like this –

But to read Daily Telegraph rock critic Neil McCormick write disparagingly about Dylan’s ‘harsh, barbed-wire timbre and his attacking delivery…but with songs like these, who cares whether he can really sing or not’ or Vanity Fair’s Mike Hogan claim that ‘On a good day, he sounds like a chain-smoking bluesman celebrating his 100th birthday. On a bad day, he sounds like a bullfrog gargling broken glass’ you would think that Dylan had somehow fallen short in his mission to sing the St Matthew Passion. An attacking, guttural delivery might not be stylistically inappropriate in the interpretation of a classical work, where the voice surrenders itself to the service of the composer and must not draw too much overt attention to its own quirks of character; but McCormick is making the mistake of shifting that particular value judgment on to Dylan, as though in the context of his own music, a ‘barbed-wire timbre’ is intrinsically a ‘bad’ or carelessly produced sound.

Lachenmann duly invoked, though, we know this not to be the case. Dylan is in dialogue with his own body. The aging process is squeezing his vocal range and tone, obliging him to reassess his technique. The emotional urgency and heat remains, but expressing it requires other technical processes. An acceptance that the aging process will leave voices sounding weather beaten and displaying their vulnerabilities is a beautiful thing. Like Marlene Dietrich under the lens, Dylan’s voice is simply being itself.

Concluding his speech in Los Angeles, Dylan observed: ‘Critics say I mangle my melodies, render my songs unrecognizable. Oh, really? Let me tell you something. I was at a boxing match a few years ago seeing Floyd Mayweather fight a Puerto Rican guy. And the Puerto Rican national anthem, somebody sang it and it was beautiful. It was heartfelt and it was moving. After that it was time for our national anthem. And a very popular soul-singing sister was chosen to sing. She sang every note that exists, and some that don’t exist. Talk about mangling a melody. You take a one-syllable word and make it last for 15 minutes? She was doing vocal gymnastics like she was a trapeze act. But to me it was not funny. Where were the critics? Mangling lyrics? Mangling a melody? Mangling a treasured song? No, I get the blame. But I don’t really think I do that.’

Dylan’s point is well made. He is not in the business of producing ugly sounds and nor, for that matter, are Lachenmann or Ustvolskaya. The sound of their music is intentioned and sincere, which is no guarantee you will actually like it, but as a culture we need to dispense with this pejorative labelling of sounds that at first feel alien and man-up to sonic reality. The whole notion of ‘training’ a voice now encompasses sinister, fascistic even, overtones. On TV talent shows a parade of wannabe singers, who like that hapless soul singer Dylan chanced upon, use precisely the same decorative figurations and flourishes to colour melodic lines: a pre-learnt, robotic, manufactured expression that exhibits all the personality and distinctiveness of a mannequin. These voices are ‘trained’ like plants are trained to follow a particular pathway, twisted around wire trellises, where they can never grow free and walk creatively tall.