The Gramophone guide to Carlo Bergonzi's greatest recordings

Alan Blyth

Monday, July 28, 2014

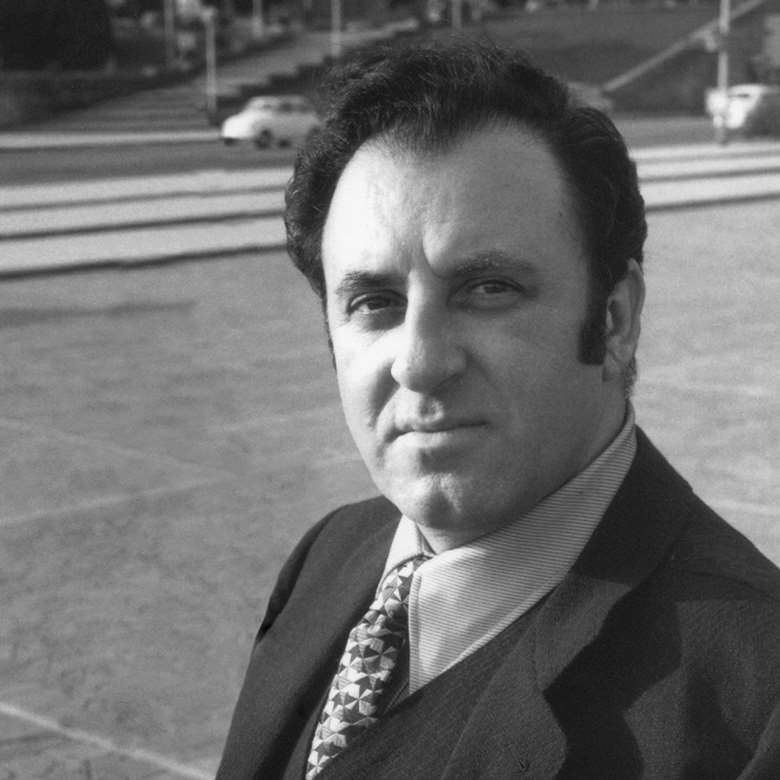

Alan Blyth surveys the life and career of the great Italian tenor who has died at the age of 90

If I declare - as I do - that Bergonzi was the greatest Verdi tenor of the last century, I will undoubtedly call down on my head the advocates of several other likely candidates. So let me say at once that Caruso had the bigger and better voice, Martinelli an even more distinctive style, Pertile the more earthy, histrionic appeal, Björling the more aristocratic manner, Corelli the more exciting timbre, Pavarotti the more immediately recognizable tone. Yet none of these (or any reader's favourite candidate) seems quite such a natural, inevitable interpreter of Verdi, or indeed of Donizetti, as Bergonzi, and none was a better musician.

Bergonzi was, and is (on disc) the ideal exponent of just about every role in the Verdian repertory, as he showed in his legendary Philips album of virtually all the tenor arias in the master's oeuvre (9/75 - nla).

His singing there, even more his earlier Verdi discs, evinces an innate feeling for shaping a line on a long breath, an exemplary clarity of diction, words placed immaculately on the tone, an authoritative use of portamento and acuti. Add to those virtues the manner by which he gives to each phrase a sense of inevitability and you say to yourself, in a mood of sheer pleasure, this is exactly how the music ought to sound. In the theatre only Otello was beyond his capabilities, though his solos are movingly sung on the Philips set.

Bergonzi looked set to be a cheesemaker like his father until his voice was discovered (he has been quoted as saying recently that tenors, like Parmesan, are no longer allowed time to mature). Trained as a baritone he began his professional life in that mode, making his debut as Rossini's Figaro at Lecce in 1948. By 1950 he came to the conclusion that he might be a tenor, retrained and made his debut in his new guise in no lesser role than Andrea Chénier at Bari in 1951, the year he was engaged to sing in Verdi's I due Foscari for Italian Radio's Verdi celebrations, a performance issued by Cetra on LP and CD. The singing there sounds a shade tentative, but by the time he made his debut at La Scala in 1953, and appeared in London at the old Stoll theatre the same year as Don Alvaro with a scratch Italian company, his voice was in place. Success at the Metropolitan followed in 1956, and he sang at the house for the following 32 years, his farewell being as Rodolfo in Luisa Miller, suitable enough when his 'Quando le sere al placido' is a model any tenor could follow.

Because he was far from being a notable actor and looked a little like the Italian tenor of caricature on stage, he never made quite the impression on the public that he deserved, but from those first performances in London (he repeated Alvaro at his Covent Garden debut in 1962), public and critics alike fell over themselves in admiration for his singing. Yet, as I well recall, he could viscerally excite an audience: on one occasion when he sang Riccardo (Gustavus, if you prefer it) at Covent Garden, he came forward in the last act, at that passage of wonderful Verdi, beginning 'Si, riverderti, Amelia', and brought the house down with the absolute conviction of his performance (you catch an echo of the effect in his performance on the RCA Leinsdorf set).

In Donizetti he was no less sincere, no less convincing. There's an unofficial video of him singing Edgardo at a performance of Lucia with La Scala in Tokyo in 1967; in the Act I duet with Scotto's Lucia, his and her readings are the pure essence of Donizetti: singing at its most persuasive - tone, phrasing and interpretative commitment in perfect balance and harmony. Again you can hear the studio facsimile of the theatrical performance on the RCA Prȇtre set. Listen to the attack at 'Qui di sposa' (disc I, track 11), then at 'Io di te memoria viva' or a little later the fine-grained accomplishment of his verse of 'Verrano a te', the voice so free and Italianate, the phrasing so seamless, the passion contained in the tone, never exaggerated. Donizettian comedy was also in his line: his Nemorino at Covent Garden was treasurable, not least because of his unlikely appearance, and his 'Una furtiva lagrima' melted all hearts.

In verismo, Bergonzi was almost as renowned as he was in Verdi and Donizetti. Turn to his account of 'Donna non vidi mai' on one of his earliest recital discs for Decca (now in the Grandi Voci CD series) and you will hear a performance so unvarnished, so impassioned, so aristocratic. On the same recital there's a version of Maurizio 's 'La dolcissima effigie' that puts most of his predecessors' readings - perhaps not Björling's - in the shade: 'bella tu sei', sung in such plangent, appealing accents as to brook no criticism. Try, too, 'Cielo e mar', taken from the complete Gioconda conducted by Gardelli: again everything sounds inevitable as Bergonzi carries through each section to its rightful climax.

Where complete sets in this field are concerned, nobody has given us such a beautifully sung Pinkerton as Bergonzi on the EMI Barbirolli set, the partnership with Scotto once more a classic. Nor should we forget another model reading, his Rodolfo, in what many consider the most authentic Bohème ever recorded: the Decca Serafin set of 1959 , where Bergonzi sings the most sensitively etched 'Che gelida manina'. For his Cavaradossi we have the evidence of the Tosca he recorded with Callas, again as stylish as you are ever likely to hear. In his Puccini, as in his Verdi, Bergonzi was always keen on interior feeling and the poetry of the invention, not on exterior display. As with Otello, Calaf was left to others. Bergonzi knew his limitations which explains why he was singing almost without loss of form into his sixties - though he did attempt Canio, a role that might be thought a shade heavy for him, with Karajan (DG) and proved again that it isn't necessary to tear a passion to tatters in creating dramatic tension.

On the Grandi Voci recital we also hear his Verdi in its pristine state (the complete set of arias was made when he was just marginally past his prime): Alvaro's Act 3 scene sung in the way admired so much at the Stoll and later at Covent Garden; then 'Celeste Aida', so much more forwardly recorded than on the complete Aida set with Karajan; and finally 'Ah, s'i ben mio'. In all three arias, with Gavazzeni as a sympathetic partner, the singing sounds easy and unaffected, intervals perfectly encompassed, breath control astonishing, shading of tone exemplary. For Bergonzi's complete Alvaro go to the EMI Gardelli set where he and Cappucilli form a near-ideal partnership in the three tenor/baritone duets, 'Solenne in quest'ora' all the better for being free from unwanted histrionics.

What else should be called in evidence? Certainly the tenor's account of Macduff's scene in the RCA Leinsdorf Macbeth. In the recitative, Bergonzi gives an object-lesson at inflecting the text, and in the aria 'Ah, la paterno mano' the ease and sheer elan of the singing fall more than gratefully on the ear. In spite of reservations already adumbrated about the sound of the Decca Karajan Aida, Bergonzi's Radames is a thing to savour. His voice never had the spinto heft of tradition in that role but with Karajan's typically sensitive support, the expected artistry of the tenor shines out. Then there's his delightful way with Italian song (try Mascagni's Serenata, so delicately caressed, so elegiac, or Tosti's L'alba separa dalle luce l'ombra - pure essence of Bergonzi, recently reissued on a Sony recital). But enough of words. Go and listen to Bergonzi, truly a gentleman among tenors.

Three recommended recordings

1) Leoncavallo Pagliacci

Sols; Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan / Karajan Read the Gramophone review

2) Puccini La bohème

Sols; Chorus and Orchestra of Santa Cecilia Academy, Rome / Serafin Read the Gramophone review

3) 'Bravo Bergonzi!' Verdi Arias

New Philharmonia Orchestra / Santi Read the Gramophone review

This article was originally published in Gramophone, April 1999