The art of film music – with John Williams, Alexandre Desplat and Clint Mansell

Charlotte Smith

Wednesday, February 8, 2017

The great film composers can connect a story with our emotions but to do that, says Charlotte Smith, they embrace the genre as a collaborative art form

From the joyful opening blast of trumpet in Star Wars, to Psycho’s discordant strings, film music has left an enduring mark in public hearts and minds. Chiefly a classical discipline, employing 19th-century instruments and compositional ideas, music of the cinema consistently reaches out to mass audiences with greater success than music of the concert hall – contemporary or otherwise. Yet traditionalists devoted to ‘pure’ classical music have often regarded cinematic compositions with a note of snobbery: how can one seriously compare a symphony of Brahms or Beethoven with the theme music from Superman?

Of course, it would be pointless to do so. But the reasons for the continued popularity of the film soundtrack and the inability of even its best examples to match the emotional complexities of the finest art music are, in fact, one and the same. For film music is a collaborative art form and as such, just a single part of a much greater and more elaborate whole. As one component of a narrative structure, film music undoubtedly benefits from the power of story-telling – conjuring a compelling nostalgia – but crucially must serve that narrative, too. And unlike the music of opera, perhaps film’s most obvious relative, it is rarely the focal point for an audience: at its most skilfully conceived, it may barely be noticed at all. In many respects, then, comparisons with symphonic repertoire are unfair, for film music is designed with an entirely different purpose in mind.

Naturally, translating cinematic music to the concert hall can be a tricky business. Conductor and arranger John Wilson, who with his handpicked John Wilson Orchestra has enjoyed recent successes at the Proms performing music from the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, has found retaining the film’s narrative structure to be helpful. ‘I was scoring Gone with the Wind recently for the BBC Symphony Orchestra and made a chronological suite. I try to get the story of the film across because otherwise you are presenting a series of disjointed music cues, which sometimes don’t stand so well on their own,’ he says. Likewise, composer Howard Shore, who arranged his own music for Lord of the Rings as a concert symphony, retained a clear chronological structure. ‘I wanted to make the symphony a narrative, so that it takes you through a journey. You begin with the prologue through to the destruction of the Ring,’ he explained at a press conference in 2006.

It is not surprising, given film music’s very close relationship with the story for which it was conceived, that such techniques prove most successful in the concert hall. Nor that concerts devoted to film music generate an enviable popularity, linked as they often are to a celebrated film franchise. But it would be wrong to dismiss the craft of film composition as merely riding the success of populist entertainment, for this is a very specific skill in its own right and one that has helped cinema to become the 21st century’s most irresistible and dominant art form.

Part of this skill is an ability to underscore without ego. In an interview in 2003 for US National Public Radio, composer John Williams described the importance of understatement. ‘When we write music for films, if we think the audience is going to give the orchestra 100 per cent of its attention we make a great mistake because we have sound effects – horses' hooves, spaceships and so on – and dialogue that have to be balanced with the music. If I do that job skilfully enough, perhaps the audience won’t notice 80 per cent of the music. It will be choreographically aligned so that it seems natural.’

It’s a sentiment echoed by The King’s Speech composer Alexandre Desplat. ‘Film music ultimately serves the movie," he tells Gramophone. "We film composers must be humble because our art is part of a larger process.’ Clint Mansell, who composed the score for Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan, found Tchaikovsky’s original score for Swan Lake (around a production of which the film is set) too rich to be used excessively. ‘There’s an incredibly psychotic element to Swan Lake, but that would overpower the film if you really let it loose. You could do that in a silent movie, but in modern films imagery and dialogue have taken over that role. So we needed to strip back the piece and rebuild it for a different medium and a different time.’

This is not to say that all film scores are ‘background wallpaper’, Desplat qualifies. ‘I always strive to write real music as much as I can.’ Longtime Kenneth Branagh collaborator Patrick Doyle agrees. ‘My music for film is written to accompany the story and serve the picture first and foremost.’ But it ‘should also communicate in its own right at all times; music should always have an in-built structure, enabling it to stand on its own.’

Desplat insists that most film composers are not the frustrated concert composers they are sometimes assumed to be. ‘If you don’t have a passion for movies, how can you become a composer for movies? I always dreamt of being a film composer. I never dreamt of being anything else.’

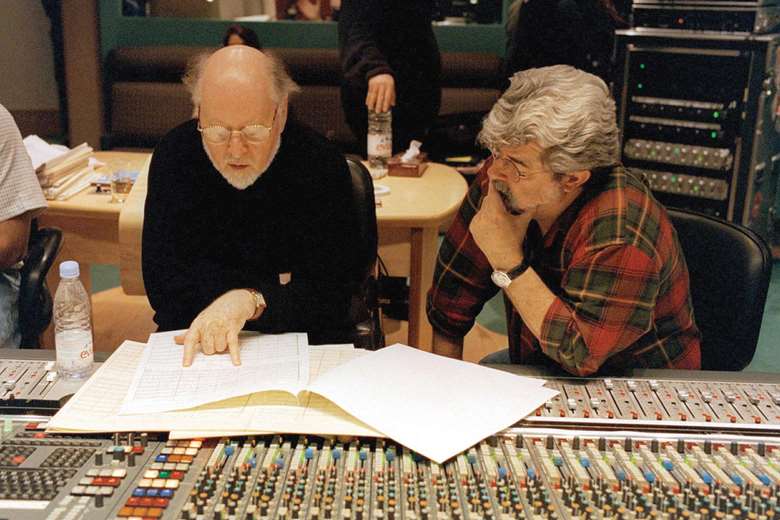

A love of the cinema might seem an obvious prerequisite, but it’s one of primary importance when considering the intimate working relationship a composer must have with his film. John Williams describes a typical day of composition, moving constantly between his projector and piano in the adjoining room. The work is fast-paced, peppered with frequent discussions with his director. ‘Before the ink is dry you print it and record it – before you even have a chance to review it,’ he says.

Such rapid, concentrated work requires an instinctive understanding of the way in which film communicates with its audience, both technically and emotionally. Desplat speaks of finding the balance between ‘function’ and ‘fiction’. ‘Function will ensure that the music fits well into the mechanics of the film, but fiction enables you to tap into another space – the invisible, the deep psychology, pain and notions of the characters. It widens the screen and has a strength, which is very special, but only when the two elements are balanced equally,’ he says. Even the best composers have fallen into the trap of failing to connect their scores sufficiently to practical elements of plot and action – the most famous example being William Walton’s ill-fated score for The Battle of Britain, which in its abstract beauty misunderstood the character of the movie and was, even more fatally, too short. The hasty supplement by the lesser-known Ron Goodwin was a better fit and contributed in no small part to the film’s success, although Walton’s ‘Battle in the Air’ was retained.

According to John Williams, the way that each scene has been edited will give the sequence a tempo of its own. ‘If you set a metronome against a particular scene, very quickly you will realise you are going too fast for the editorial rhythm or you are going too slow and need to catch the editorial breathing of the film.’ Not only do the images and events have this kinetic aspect, but so too do the stresses and patterns of dialogue. The composer’s music must move within the multiple rhythms already established, enhancing and reinforcing this design: to introduce alien or unsympathetic tempi would unbalance the harmony of the film.

This is all the more important, Williams believes, because music is necessary to reinstate a sense of cohesion in a narrative that by necessity begins its life in separately filmed blocks. ‘The editor cuts it all together, but somehow the soul isn’t quite there. There are certainly great film sequences that don’t need music and shouldn’t have it, but in general music heals the events that have caused the film to be made.’

Williams’s ‘soul’ is analogous to Desplat’s ‘fiction’ – an extra dimension, which articulates for the audience the tone and character of the work. Dario Marianelli, composer of soundtracks for Pride and Prejudice and Atonement, believes film music ‘occupies a very interesting space’. ‘Music can tap into a deep buried part of our psyche where emotions play a part, but I suspect there is more,’ he says. ‘It is possible for music to be both enlightening and emotional, atmospheric or decorative. Music can be used to structure narrative, or help the suspension of disbelief that is necessary to enjoy a fictional story.’

On occasions, music written for cinema has even been used to inspire actors during filming. For Branagh’s Henry V, Doyle composed the Non nobis, Domine chorus following a detailed discussion with his director, and an electronic mock-up of the score was played during the filming of the Battle of Agincourt’s aftermath.

Such happy foresight can come about only when directors understand that the process of film-making is ‘something you have to share,’ says Desplat. In a highly collaborative environment it stands to reason that the better the balance between cinematography, editing, art direction, screenplay and music, the finer the finished film. So partnerships between like-minded composers and directors are often sustained over a large body of work. John Williams and Howard Shore have worked with directors Steven Spielberg and David Cronenberg respectively for more than 30 years. Clint Mansell has scored all five of Darren Aronofsky’s films and Dario Marianelli worked with British director Joe Wright on three consecutive projects. At the heart of each successful partnership is ‘a love of discovery’ and ‘discussion’, says Marianelli. ‘We meet very early in the process and talk about the story and what might be interesting to explore musically. It is an organic process: the score grows with the film, as we work in parallel. Both the music and the movie gradually find their place and shape.’

While concessions for dialogue, photography, editing – not to mention the director’s vision – might seem too controlled and structured an environment for unbounded musical creativity, Mansell is ‘liberated’ by the experience. ‘That confinement forces you to think in new ways, and making it work within that structure – while at the same time satisfying your own creative needs – is very rewarding.’ It’s a feeling shared by many composers working in the industry – that film’s collaborative aspects, rather than stifling the creative process, help to generate ideas. ‘The director wants you to open windows and gates he never considered for his film,’ says Desplat.

Music conceived by such dynamic, enriching means must surely be a good thing and its existence alongside music written for the concert hall can only enhance the variety and scope of the classical landscape. ‘There is a lot of beautifully written, extremely well-crafted, ear-catching music that has been written for films over the years,’ says John Wilson. ‘I think there is definitely a place for cinematic music, and its recognition is well deserved.’ G

This article originally appeared in the April 2011 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing to Gramophone, visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe