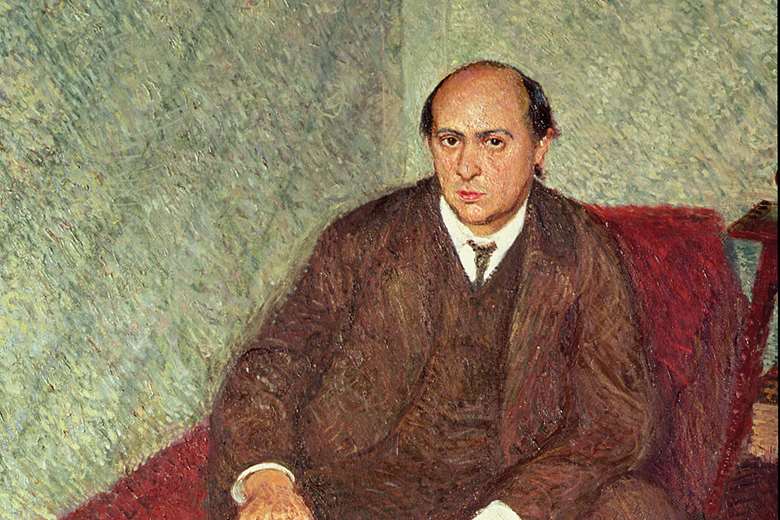

Schoenberg’s Second String Quartet: a guide to the best recordings

Richard Whitehouse

Friday, November 1, 2024

Schoenberg’s influential String Quartet No 2 both acknowledged and broke away from tradition. Richard Whitehouse surveys its recorded history

The 150th anniversary year of Schoenberg’s birth has reopened well-rehearsed arguments on the nature and consequences of his legacy, while bringing renewed attention to those seminal works that define much about Western music over the course of the 20th century. If not the most radical, the Second String Quartet remains among the most influential, not least through its becoming an exemplar for how subjective experience can be transmuted into music whose expressive power is accentuated by its formal focus – resulting in a perfectly realised artwork.

Background

Schoenberg began this piece in March 1907, almost a decade after a String Quartet in D duly announced his arrival as a composer demonstrably in the ‘Viennese tradition’. What followed was his determined effort to fuse the motivic discipline of that lineage from Haydn to Brahms with the harmonic potency of Liszt and Wagner. Hence the harnessing of an abstract medium directly to a poetic source in his string sextet Verklärte Nacht (1899); its symphonic evolution pursued in his symphonic poem Pelleas und Melisande (1902‑03) then his First String Quartet (1904‑05); and the integration of the customary four movements into a continuous entity compressed to barely half this length in his First Chamber Symphony (1906). Eighty-four years after Schubert blazed a trail in his Wanderer Fantasy, Schoenberg decisively realised its single-movement potential.

Much has been made of the attendant marital crisis as the Second Quartet was being written, as though this itself determined the musical outcome. In fact, the piece had been extensively sketched prior to this – its mood of agitated resignation carried over from a Second Chamber Symphony that Schoenberg worked on and (temporarily) abandoned in the preceding months. It was surely uncertainty over how the work should evolve that saw his apparent return to ‘first principles’ in the summer of 1908 with those four separate movements of his Second Quartet.

Overview

Formally, this piece alludes to without being beholden to formal precedent. Marked Mässig (moderate), the opening movement centres on F sharp minor for its terse sonata design of an impulsiveness undercut by enervation. The second movement (Sehr rasch – very fast), centres on D minor in a ternary design whose sardonic outer sections frame an explosive trio; allusion to the popular ballad ‘O du lieber Augustin’ conveys a weary dismay. The latter two movements set texts by Stefan George in his anthology Der siebente Ring (‘The Seventh Ring’). The slow ‘Litanei’ (‘Litany’, marked Langsam) references E flat minor for four variations of a cumulative intensity offset by a laconic introduction and distilled into an anguished coda. The finale, ‘Entrückung’ (‘Rapture’, Sehr langsam – very slow), revokes self-laceration for self-denial, moving fantasia-like from its keyless prelude to a postlude that attains the nirvana of F sharp major to which the whole work has covertly been heading. Ending on a tierce de Picardie, Schoenberg does not break the bounds of Classical tonality so much as relativise some three centuries of Western music.

Premiered at the Bösendorfersaal in Vienna on December 21, 1908, by the Rosé Quartet with soprano Marie Gutheil-Schoder, the Second Quartet met with consternation spilling over into antagonism, but its significance was recognised at the outset – not least its combining of voice and strings, giving rise to a lineage of quartets from Milhaud’s Third (1916) to Ferneyhough’s Fourth (1989‑90). Schoenberg’s concept of a work with clearly demarcated formal divisions that between them effect an ultimate catharsis was finally achieved in his String Trio (1946).

The earliest recordings

It was through film composer and Schoenberg admirer Alfred Newman that the first recording of these quartets came about, played by the Kolisch Quartet in Schoenberg’s presence and to his satisfaction. Here the Second’s initial movement has a visceral charge that is carried over to a capricious scherzo, its mordancy contrasting with the sheer anguish of ‘Litanei’ then the benedictory repose of ‘Entrückung’. Clemence Gifford, a haunting if never alienated presence, articulates emotion in the latter movements with unfailing insight. A yardstick in every sense.

Ironically the Kolish set found commercial release in 1950, only just ahead of the Juilliard Quartet’s first recording, issued in the UK a decade hence. Fastidiously played if a little too circumspect as an overall reading, it is at its best in the latter two movements where the expressive poise of Uta Graf eloquently counters any excessive objectivity. Clearly the need to realise this music with absolute precision was the guiding factor at this stage in the Juilliard’s traversal, abetted by sound whose unsparing focus but flattened-out dynamics offsets any hint of spontaneity.

From the ’60s to the ’80s

No such issue affects the Ramor Quartet’s reading, vividly recorded such that Schoenberg’s disquieting vision is projected with unremitting impact – intonational quirks and all – with Maria Theresia Escribano uninhibitedly responsive to those widely contrasted later movements. At the opposite pole of the emotional spectrum, the New Vienna Quartet emphasises its Austro-German lineage, bringing taciturnity then a deadpan humour to the earlier movements, with Evelyn Lear never less than alluring if missing the ultimate plangency in the George settings.

Many listeners will have first encountered this music via the LaSalle Quartet, whose Second Quartet was for long the benchmark in terms of lucidity and unforced pursuit of an emotional equilibrium over all four movements. With hindsight it now feels just a little pale in response, tracking the work’s emotional follow-through at a (conscious?) remove, with Margaret Price adding a pellucid if distanced vocal. Those acquiring it should seek out the original LP set or first CD reissue for the extensive bio-documentary study edited by Ursula von Rauchhaupt.

In contrast, few will have heard the 1972 performance by the Mari Iwamoto Quartet before its belated emergence on YouTube, but this is one to savour – languorous then acerbic in the earlier movements, with Yonako Nagano (who made a fine version of Schoenberg’s Hanging Gardens cycle) fearless to the point of recklessness in what follows. Rarely can the music’s essence have been conveyed this acutely, so making its ‘official’ reissue the more necessary.

The Juilliard Quartet’s second traversal finds this ensemble probing the music’s depths more consistently. Here, too, the first movement’s discontinuity, the multilayered irony of the scherzo (its ‘Augustin’ allusion sounding grimly fatalistic) then the febrile anguish of ‘Litanei’ become part of a cumulative trajectory, with Benita Valente’s almost declaimed vocal in ‘Entrückung’ enhancing the aura of other-worldly transcendence. Its timely reissue, in sound that is a vast improvement on the constricted LPs, reaffirms this among the finest interpretations yet made.

It might not enjoy a comparable reputation in this music, but the Sequoia Quartet was an able and questing ensemble. Its discography includes a 1979 Schoenberg Second Quartet (Nonesuch LP, 4/82), whose understatement does not lack character, with a warmly confiding vocal by Bethany Beardslee. In a period with few recordings of this music – save one by the Borodin Quartet and Lyudmilla Belobragina that never made it to the West (Melodiya, 1978), and another from the Gewandhaus Quartet with Sibylle Suske that enjoyed limited distribution (Berlin Classics, 1985) – the Sequoia Quartet’s recording does not deserve to be forgotten.

From the ’90s to 2010

A steady stream of releases began with that from the Arditti Quartet, its modernist inclinations evident in a restless first movement then an astringent scherzo with little hint of irony. Slightly more yielding expressively, the later movements feature Dawn Upshaw as an assured vocalist whose supplicatory eloquence feels more than a little self-conscious. Greater expressive unity informs the Arditti’s 2014 live account with an agile contribution by Franziska Hirzel (BMN Audiophil), but the somewhat restive background ambience and brittle sound quality do this few favours.

The Brindisi Quartet give an able account, intonationally secure if interpretatively no more than the sum of its parts, abetted by Christiane Oelze’s understatement in the later movements, which rather fails to convey the visceral nature of Schoenberg’s writing to the extent needed. By contrast, the Britten Quartet pitch straight in, the opening movements’ blend of impetus and angularity setting a persuasive course the remainder does not quite fulfil – not least with Amanda Roocroft balanced slightly too forwardly so that key instrumental detail is obscured.

No such reservation affects the Pražák Quartet, whose eliding effortlessly between eras and aesthetics is potently demonstrated in this work. Interpretatively it is the bracingly impetuous scherzo then vivid take on ‘Litanei’ that come off best, the first movement a little short-winded emotionally and Christine Whittlesey’s poise in ‘Entrückung’ at variance with this ensemble’s lithe detachment. The outcome is a reading which, by reining in the extent of the crisis to be overcome, leaves not enough to be transcended emotionally in its all-too-aloof closing stages.

Few championed the Second Viennese School as consistently as the Schoenberg Quartet yet, while Susan Narucki is an intelligent vocalist, emotional intensity is erratic. That they render this combative music with overmuch empathy is not necessarily a fault in the right direction. Her second recording finds Oelze drawing considerably more expressive remit from the latter movements, abetted by a keen response from the Leipzig Quartet, making for a reading in the Austro-German lineage whose playing innovation off against tradition is the more arresting.

Was its being released on a label known mainly (at least in the UK) for historical reissues that caused the Schoenberg cycle from the Aron Quartet to be almost wholly overlooked? Amends are overdue if so, as this is a notable achievement and not least for a Second Quartet in which security of playing aligns to an interpretation that, while it might afford few overt revelations, conveys the sheer fervency of its composer’s inspiration with an emotional acuity matched by relatively few others – not least with Anna Maria Pammer eloquently attuned in her response.

The recording by the Manfred Quartet is notable for its gradual accumulation from circumspect initial movements via an ominous ‘Litanei’ to a luminous ‘Entrückung’. A suitably hieratic vocal by Marieke Koster, plus apposite early quartets by Webern and Berg, make it worth returning to. Conversely, that by the Fred Sherry Quartet is in a Schoenberg miscellany whose diversity is almost its undoing. Its Second Quartet is best in the simmering unease then brittle humour of the opening movements, with Jennifer Welch-Babidge secure if generalised in what follows.

Both the Petersen Quartet and Christine Schäfer are among the most perceptive Schoenberg interpreters of recent decades, and their Second Quartet is mostly impressive – trenchant and agile in the instrumental movements, with an underlying vulnerability that comes to the fore in what follows. Schäfer’s contribution brings an almost confiding intimacy in the finale, so making its couplings of Webern’s jejune Langsamer Satz and the Largo desolato finale from Berg’s Lyric Suite, here with its questionable vocal lamination, the more unsatisfactory.

At least the Diotima Quartet rendered the Berg complete, alongside all of Webern’s 1911‑13 miniatures, when they recorded the Schoenberg. Lighter in tone or expression than many, with Sandrine Piau an agile and almost skittish vocalist in the latter movements, they relocate the music away from a nascent expressionism to the more objectified modernism of a later era, from which vantage this account is best heard recoupled within an integral cycle of Second Viennese School quartet music, where the ensemble’s interpretative aims become clearer.

The most recent recordings

Rightly praised in these pages for having tackled Schoenberg’s four numbered quartets near the outset of their career, the Asasello Quartet give one of the more expansive recorded accounts of the Second. There is nothing tentative about the first movement’s simmering unease or the scherzo’s eruptive irony, Eva Resch duly providing an ideal foil with her understated yet finely drawn vocal and projecting George’s sentiments with enviable clarity. That this ensemble may one day penetrate even further into this music need not pre‑empt their achievement herein.

Coupled with Brahms’s Second Quartet, the Kuss Quartet offer a lucid reading that undersells the music’s emotional power. Nor is the alluring Mojca Erdmann fully in sympathy, ‘Litanei’ eschewing the ultimate anguish as surely as ‘Entrückung’ misses its eventual transcendence. Given Schoenberg’s recourse to precedent, the Amaryllis Quartet’s framing his Second with Mozart’s Hunt and Dissonance Quartets might seem plausible. Yet this fails as an overall concept, with Katharina Persicke’s pure tones not quite sustaining an effortful ‘Entrückung’.

Contrast this with the version from the Gringolts Quartet, part of a cycle the more impressive for drawing the four quartets into a logical and cumulative unity. Listen to how the yearning unease of the Second’s opening movement is brusquely offset by the scherzo’s sarcasm then intensified by the anguish of ‘Litanei’, Malin Hartelius as attuned to its supplication as to the self-absorption of ‘Entrückung’. She and this ensemble complement each other ideally in a reading that takes no risks yet brooks no compromise in its conveying of a singular musical vison.

Few will have encountered the Kairos Quartet (Edition Zeitklang, 2016) in an account that stresses the music’s febrile intensity as wholly as its radical implications but, with Angelika Luz commanding in voice and a trajectory that places the Schoenberg finale after Sabine Panzer’s unnerving Mientras, this provides a fascinating listen. More so, indeed, than that by the Richter Ensemble, which is on occasion tentative or even effortful, with Mireille Lebel an able if anonymous vocalist and a coupling replicating that by the Manfred Quartet, albeit with lesser conviction.

More absorbing is the Arod Quartet’s ‘The Mathilde Album’, Webern’s Langsamer Satz and Zemlinsky’s Second Quartet framing the Schoenberg. Impulsively spontaneous, this latter convinces save for too discursive a finale, Elsa Dreisig the sensitive if over-circumspect vocalist. Equally well coupled is that from the Heath Quartet, the Webern and Berg’s Op 3 preceding a Schoenberg most perceptive in an incisively agile scherzo, and an ‘Entrückung’ whose distanced intensity accords with Carolyn Sampson’s thoughtful rendition of the text.

The most recent recording is one of the most imaginatively coupled – the Emerson Quartet’s ‘Infinite Voyage’ journeying through settings by Hindemith and Chausson, separated by Berg’s Op 3 then concluded by Schoenberg’s Second Quartet in a reading whose relative swiftness exudes a concentration and energy that finds both its culmination and transcendence in a finale where Barbara Hannigan’s high-flown eloquence is at its most stentorian. In what proved their last commercial release, the Emerson could not have achieved a more impressive signing‑off.

Arrangements

While never intended as autonomous songs, ‘Litanei’ and ‘Entrückung’ are viable with piano and were arranged so in 1912 by Berg. Part of a fascinating anthology of Schoenberg transcriptions, Claudia Barainsky and Urs Liska accord them ample justice in this guise (Capriccio).

A version with string orchestra arranged by Schoenberg in 1919 met with little attention until after its revision a decade on. Performed by Dimitri Mitropoulos on a riveting 1945 broadcast with Astrid Varnay and the NBC Symphony, or Michael Gielen in a tense 1975 reading with Slavka Taskova and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, it went unrecorded until Peter Gülke’s edgy 1985 traversal with Eva Czapó and the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie. Yuli Turovsky from 1992 with Nadia Pelle and I Musici de Montréal is incisive while limited in scale. Jean-Jacques Kantorow in 1994 with Christina Högman and the Tapiola Sinfonietta secures lucid textures if little emotional force. Esa-Pekka Salonen in 1996 gets lively playing from the Stockholm Chamber Orchestra but lacklustre singing by Faye Robinson. Jac van Steen in 2005 with Musikkollegium Winterthur and Claudia Barainsky has an expressive poise and intensity to make it the preferred option.

Conclusion

The proliferation in recordings over the past three decades of Schoenberg quartets in general, and the Second in particular, has opened out the field considerably as regards couplings and interpretation. Allegiance to cycles from earlier eras such as the Kolisch or (second) Juilliard remains undimmed, while those conceptual releases from the Arod and Emerson merit a place at or near the top of any shortlist. Any outright recommendation is likely to be subjective but, at this vantage, such a choice would be the Gringolts Quartet. As the most recent cycle of the four ‘official’ quartets, it confirms the validity of experiencing these works as an emerging or cumulative totality; if it is not the most inclusive such sequence of the 20th century, then it is among the most significant for what this represents in terms of intellectual and spiritual endeavour.

Almost 120 years on from the crisis provoking or at least informing its creation, Schoenberg’s Second Quartet is not merely a totemic statement but music whose challenges are rewarding and indeed enjoyable – not least when an ensemble as formidable technically and sensitive interpretatively as the Gringolts is on hand to convey its disquieting yet enthralling essence.

The Ultimate Choice

Hartelius; Gringolts Qt BIS (BIS2267)

Part of the most recent Schoenberg cycle, the performance by the Gringolts Quartet unfolds the Second Quartet with a seamless cohesion and unforced intensity closest to the interpretative ideal – palpably so in a finale where Malin Hartelius eloquently articulates its rapt transcendence.

Read the original Gramophone review

The Conceptual Choice

Hannigan; Emerson Qt Alpha (ALPHA1000)

Assuredly a high for the Emerson Quartet’s leave-taking, ‘Infinite Voyage’ ends in a Second Quartet whose technical finesse allied to emotional acuity makes for an account of manifest insight, where a visceral contribution from Barbara Hannigan is an inevitable enhancement.

Read the original Gramophone review

The Classic Choice

Valente; Juilliard Qt Sony Classical 19658 82720-2

It may have taken decades for the Juilliard Quartet’s second traversal to be reissued in full, but the wait proved well worthwhile in respect of a Second whose disjunct emotional contrasts are harnessed towards a serene conclusion where Benita Valente is as alluring as she is confiding.

The Historic Choice

Gifford; Kolisch Qt Music & Arts CD1056

Schoenberg openly acknowledged the debt he owed to Rudolf Kolisch’s ensemble in bringing these quartets to life, and this earliest recording remains among the most expressively intense, not least in the latter movements, where Clemence Gifford is a suitably other-worldly presence.

Selected Discography

Recording Date / Artists Record company (review date)

1936 Clemence Gifford / Kolisch Qt Archiphon ARC103/4 (1/94); Music & Arts CD1056 (9/03)

1952 Uta Graf / Juilliard Qt Sony Classical 19658 82720-2 (3/60)

1962 Maria Theresia Escribano / Ramor Qt Tuxedo TUXCD1037 (7/62)

1967 Evelyn Lear / New Vienna Qt Philips 464 046-2PM2 (3/82, 2/00)

1969 Margaret Price / LaSalle Qt DG 414 994-2GCM4 (4/88); 479 1976GB6

1972 Yonako Nagano / Mari Iwamoto Qt youtube.com

1975 Benita Valente / Juilliard Qt Sony Classical 19658 82720-2 (1/78, 8/96)

1993 Dawn Upshaw / Arditti Qt Naïve MO782024 (1/95)

1994 Christiane Oelze / Brindisi Qt Metronome METCD1007 (6/96)

1994 Amanda Roocroft / Britten Qt EMI 555289-2 (7/95)

1994 Christine Whittlesey / Pražák Qt Praga Digitals PRD250056

1996 Susan Narucki / Schoenberg Qt Chandos CHAN9939 (A/01)

1999 Christiane Oelze / Leipzig Qt Dabringhaus und Grimm MDG307 0935-2

2003 Anna Maria Pammer / Aron Qt Preiser PR90572

2004 Marieke Koster / Manfred Qt Zig-Zag Territoires ZZT041201

2004 Jennifer Welch-Babidge / Fred Sherry Qt Naxos 8 557521 (2/06)

2007 Christine Schäfer / Petersen Qt Phoenix Edition 133PHOENIX

2010 Marie-Nicole Lemieux / Diotima Qt Naïve V5240 (8/11); V5380 (6/16)

2014 Eva Resch / Asasello Qt Genuin GEN16429 (9/16)

2015 Mojca Erdmann / Kuss Qt Onyx ONYX4166 (1/17)

2015 Katharina Persicke / Amaryllis Qt Genuin GEN16438

2016 Malin Hartelius / Gringolts Qt BIS BIS2267 (10/17)

2018 Elsa Dreisig / Arod Qt Erato 9029 54255-2 (11/19)

2018 Mireille Lebel / Richter Ens Passacaille PAS1093

2021 Carolyn Sampson / Heath Qt Signum SIGCD712 (8/22)

2022 Barbara Hannigan / Emerson Qt Alpha ALPHA1000 (10/23)

String Orchestral Arrangement

1945 Astrid Varnay; NBC SO / Dimitri Mitropoulos Music & Arts CD1214 (11/08)

1975 Slavka Taskova; Frankfurt RSO / Michael Gielen SWR Music SWR19063CD (10/19)

1985 Eva Czapó; Junge Deutsche Philh / Peter Gülke EMI 747923-2 (6/87)

1992 Nadia Pelle; I Musici de Montréal / Yuli Turovsky Chandos CHAN9116

1994 Christina Högman; Tapiola Sinfonietta / Jean-Jacques Kantorow BIS BIS-CD703 (10/95)

1996 Faye Robinson; Stockholm CO / Esa-Pekka Salonen Sony Classical SK62725

2005 Claudia Barainsky; Musikkollegium Winterthur / Jac van Steen Dabringhaus und Grimm MDG901 1425-2

This article originally appeared in the November 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue – subscribe today