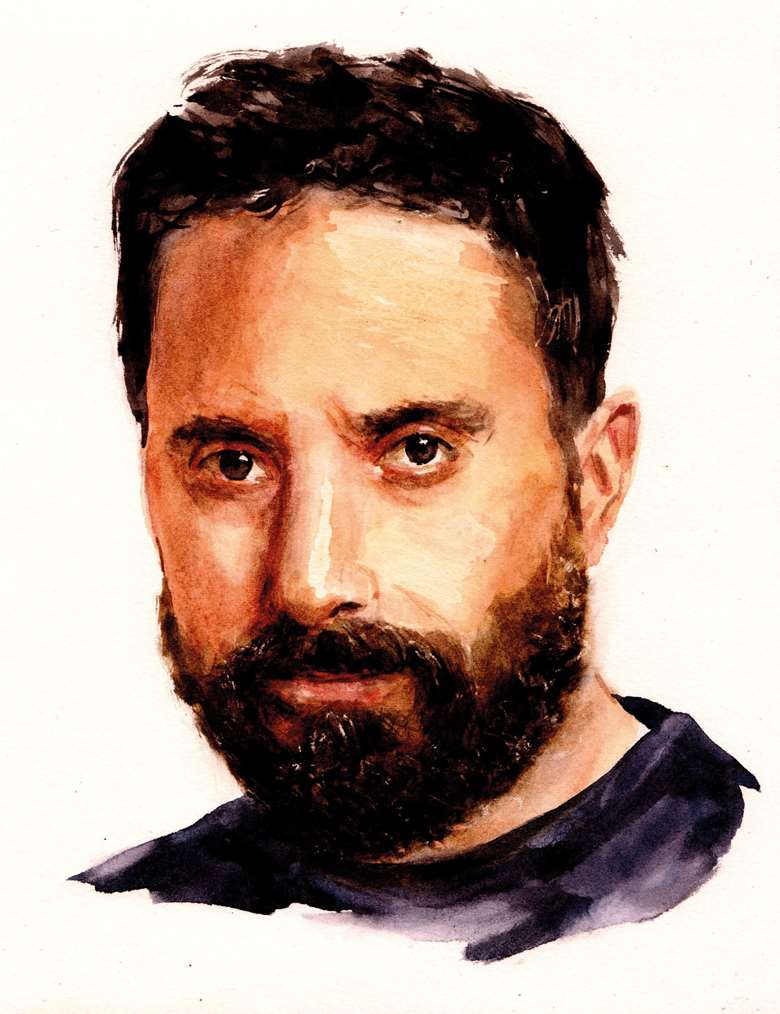

Pablo Larraín interview: ‘Maria Callas somehow became the sum of the tragedies that she played on stage’

Friday, January 3, 2025

The director of ‘Maria’ on the recordings of Callas, and on what makes a great film score

Growing up, I was very lucky – my parents would usually get season tickets for the opera house, so I would go to see ballet, concerts and of course opera. But I got into classical through listening to recordings, again thanks to my parents – they would listen to Mahler and Beethoven. We also had a great Chilean pianist called Claudio Arrau who dedicated his life to Beethoven sonatas.

But what happened to me is that as I grew up, of course, rock and pop music got into my life – like everybody in the ’80s – and I was always trying to understand: how did we get there, what was the musical transition from the Baroque and Romantic composers to David Bowie, what was the journey, cultural-wise? And when I became a filmmaker, I turned to classical music and found the people that had some form of instrumentation that I thought could be compared to what we understand as pop or rock music – people like Stravinsky, Bartók, even Wagner.

Most of what contemporary film score music is comes from the opera composers who had to compose dramatic music. There’s a lot of music in Maria which we just re-recorded and took the voices out, using the music only. We just use the music that sustains and contains the voices – and that’s very much what a film score is. What I think is so interesting, and I say this having the luck to work with people like Mica Levi or Jonny Greenwood, is that what these incredible genius composers can do is really elevate the music for film to the right place. This is what you can take from opera and symphonic music: you have one idea, which is the picture and whatever’s going on with the characters and story; then you have another idea which is the music. If the music is saying the same thing as the picture, then the ideas are small and repetitive. But if both ideas are different, then once put together, there’s a third idea that comes out, one that can take the film into a place that is unpredictable for everyone; for me, for the people making it, for the audience – and that is the most gracious and beautiful way, when film music can take you to a different place.

I didn’t want to make a movie about Maria Callas and not use certain pieces of music that were so emblematic to her – if you want to open her legacy to more people, you need to put certain pieces that are important in. Maria Callas somehow became the sum of the tragedies that she played on stage. She played so many tragic characters who died at the very end of the opera, and I think they became some kind of ghosts in her life. And we wanted to play with that, to show that.

Opera is a live kind of performance, where there are no microphones – or they are very far away, above the stage or very close to the orchestra. Small microphones that would not interfere with the live experience. And those were the recordings that Maria Callas really cared about – performances that people had recorded from their seats. The recordings made in a studio, with a microphone a few feet away – that is not the sound of opera. It could sound better, of course, it’s more beautiful for other people – but it has such a different texture. Maria Callas did not listen to her own voice until very late in her life, when she wanted to know how her voice sounded in her prime. The distinction between what’s live and what’s recorded in a studio is something that truly, truly affected her.

Some of the critics – because she was highly criticised while she was alive, let’s not forget about that – were saying, in this opera, or this act or aria, she didn’t hit this or that note. But it was even more moving because of that. They were tough with her about every single little mistake that she would make, but paradoxically that was exactly what made her more unique and beautiful.

‘Maria’ is available on Netflix, and is in UK cinemas from Jan 10