Meeting Stravinsky, by Tony Palmer

Tony Palmer

Friday, March 19, 2021

The filmmaker recalls how tea at The Savoy led to making a Stravinsky centenary tribute

Two phone calls which quite changed my life. The first, in September 1965, not long after I had left university and joined the BBC. When the phone rang in my tiny office on the fifth floor of the East Tower at White City (now a ‘luxury apartment’), I knew the voice, that of an agent friend Robert Paterson, but the message was absurd. ‘Mr Stravinsky would like to meet you. Can you come to tea at The Savoy Hotel tomorrow afternoon?’ ‘Very funny,’ I said, and put the receiver down. Seconds later the phone rang again. ‘No, this is serious,’ said Paterson. ‘Pull the other one,’ I replied. ‘Stravinsky can’t possibly have heard of me.’ But then, I thought, how could I turn down an invitation to tea with one of the greatest composers of the 20th century?

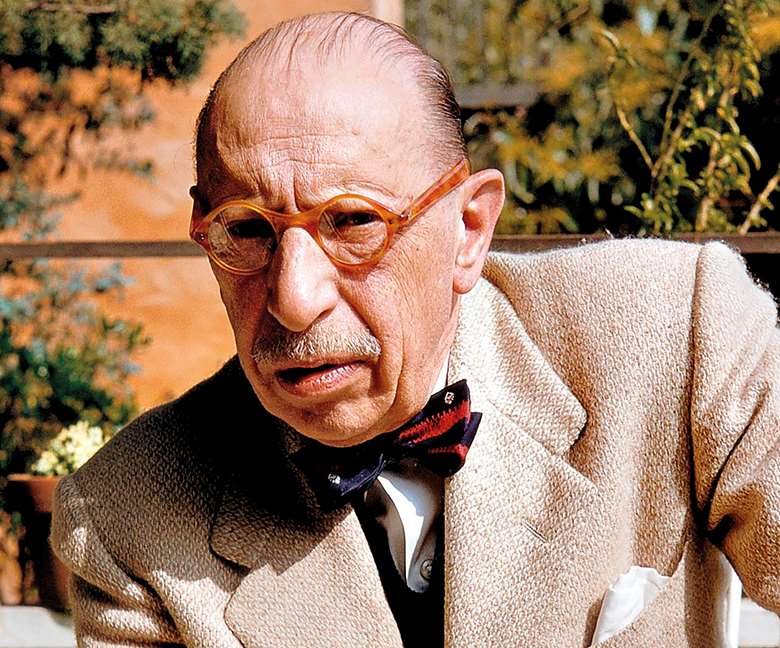

And so, the following afternoon wearing my best and my knees shaking like hell with nerves, I was ushered into the suite occupied by Igor Stravinsky. He was not there. Paterson whispered to me that he was next door having a blood test/transfusion or some such, but would be here shortly. Eventually, in came this five feet two inches of electricity. He bowed. I bowed, but given that I am six feet tall, bowing low enough to show proper respect became a distinct comedy of manners, especially as the great man, ever the courteous gentleman, insisted on calling me ‘Sir’. Luckily, I never called him ‘Igor’ because, as I later discovered, had I done so I would have been incinerated on the spot.

He sat down. I sat down. Eventually, prompted by his amanuensis Robert Craft, he asked, in a language that can only be described as peculiar (he never mastered English): ‘Is it true that you know The Beatles?’ Already tongue-tied in his presence, all I could mutter was ‘Yes’ followed by ‘Sir’. Craft now intervened. ‘Do you think it’s possible to arrange a meeting with John Lennon? The Maestro would really appreciate this.’

Robert Paterson, who was representing Stravinsky during his visit to the UK (his last, sadly), told me that it had been his idea. No more than a casual aside, but one which the Maestro had seized upon as something that might be fun. Apparently such bon-bons were the spice of his life. I told the Maestro that I would do my best, and later that day made contact with Lennon, already a friend of a few years, who was, to put it mildly, much intrigued. Whether that meeting ever took place I do not know, but it certainly opened the door between me and the great man. Not only was I invited backstage at the concert he gave two days later in the Royal Festival Hall but, more importantly, I was invited by Craft to visit them when next in New York.

This I did, and later had the honour of attending his funeral in Venice, and later still accepting the invitation – actually it was more of a challenge – issued by Madam Vera Stravinsky and Robert Craft to make the semi-official 100th birthday film to celebrate the Maestro and all who had sailed in the great ship Stravinsky. We were incredibly lucky: we managed to reach Stravinsky’s three surviving children, as well as the last two dancers alive who had actually performed in the notorious 1913 premiere of The Rite of Spring, George Balanchine, Serge Lifar, Diaghilev’s secretary, Nijinsky’s daughter, Benny Goodman, Nicolas Nabokov, Rimsky-Korsakov’s granddaughter, Nadia Boulanger, Georges Auric, the dancers Danilova and Tamara Geva, and of course Mrs Stravinsky herself. Most of these first-hand witnesses were dead within a very few years. We had got there just in time.

I say ‘challenge’ because my introduction to this journey was hardly encouraging. I was flown to New York by Craft and told that first I must discuss matters with Stravinsky’s lawyer, the formidable Arnold Weissberger. I duly arrived at his office and upon entering was told to stand against the wall while he took a photo of me. ‘Necessary’, he said, ‘because otherwise I would never remember who the hell you are,’ so my name was duly inscribed on the polaroid. ‘Now then,’ he went on. ‘You realise this film is impossible.’ Ah, I remember thinking. Good of you to tell me up front. ‘There are two camps. The first, the three surviving children. The second, Robert Craft and the widow. The children will refuse point blank to appear in any film with Robert Craft, whom they loathe. Craft, on the other hand, will refuse point blank to appear in any film with the children or their offspring. So we thought …’ (and here there was a long pause) – ‘Who do we know who is so stupid as to undertake this, and our thoughts immediately lighted upon you.’ Admittedly he did then laugh. I did not.

Eventually, the film was made and included both camps and both seemed satisfied. Craft became a lifelong friend, and Théodore, the elder son and a painter, was so pleased that he gave me one of his original paintings of the premiere of L’Histoire du Soldat. He only made one objection to the entire two-hours-and-45-minutes film. I included a remark by Craft that in his Russian days Stravinsky had been a usurer – he had loaned money. ‘Only to other members of his family,’ said Théodore, a fact he found highly amusing.

So what did I discover about Stravinsky the man? Nicolas Nabokov told me that, above all else, Stravinsky was a hedonist. ‘He loved all the pleasures of life,’ he said. ‘He loved to eat; he loved good wines, pretty girls.’ ‘He hated familiarity,’ one of his pupils, Alexei Haieff, confided. ‘If someone called him Igor, that would be the end. He would hate that man. He would remember his rudeness for years: “That awful upstart,” he would say. “How dare he call me Igor?” He loved wine and whisky, and always carried a bottle of Chivas Regal in his luggage. In fact, he liked his booze in any form and would often get slightly “exhilarated”. And he smoked!’ ‘He was like a dandy, but a caricature of a dandy,’ Nijinsky’s daughter told me. ‘He liked squares either in a chequered jacket or in chequered pants with a plain jacket that didn’t match at all. But he also liked to give the impression of a school teacher at school with kids that were not behaving themselves. Very stern looking.’

He also had an extraordinary sense of irony. Everything for him was really rather funny, including his own health. ‘He was an appalling hypochondriac,’ Craft told me. ‘True, he was often ill, and his health had often suffered as a result of set-backs in his creative life. After the riots during the first performance in Paris of The Rite of Spring, for instance, he had caught typhus, almost as a reaction, and been very gravely ill. But he had colds all the time, for example. He had tuberculosis, and had spent months in a sanatorium. He suffered from bleeding ulcers. He had crippling headaches. He had everything. He was kept alive in the end by constant blood transfusions. But he kept all his X-rays and studied them. Charts, medical diaries, statistics about his health, these fascinated him. Once, I remember, he took some radioactive capsules for an X-ray. “Now I am surely lighting up like a lightning bug,” he said.’

‘My father was extremely faithful,’ his second daughter Milène told me. ‘He may not have gone to church very often, but he always had his icons around his bed, and before he went away on a trip he would always give us his blessing.’ ‘My parents took religion literally,’ Soulima his second son added, ‘which none of us four children really appreciated. I suppose it would have been alright had we been monks in a monastery. But praying together at home, in front of a few small icons, never seemed quite right.’ ‘Music praises God,’ Stravinsky told me as if it were self-evident. ‘Music is as well or better able to praise him than the actual church building itself and all its decoration. I believe in the person of The Lord,’ he said, stabbing his finger at me, ‘and in the person of The Devil.’

I remember when we were in a restaurant in New York on that first visit after London and, as was customary, the waiter was pouring water into everyone’s glass. Stravinsky put his hand over his glass and said: ‘Water is for de … feeet.’ I did not have the temerity to ask him what he meant. Was this a reference to some great Russian battle, maybe Waterloo? Years later, when I was making the film, I asked Madam Vera if she recalled that remark, and what the Maestro had meant. ‘Ah, silly boy,’ she said to me. ‘Water is for the feet, clearly a reference to Christ washing his disciples’ feet.’

‘Stravinsky was concerned in everything he did’, Nicolas Nabokov said, ‘with ritual and with belief, Christian belief. One cannot speak of him as a religious composer, however. But one can say that very few composers of our century have dealt with religious subjects as did Stravinsky.’ The dedication of the great Symphony of Psalms, for instance, is ‘to the glory of God’, which happened to be inscribed over the door of the church in the square of Morges in Switzerland, where Stravinsky and his family were living in exile at that time in Maison Bornand. And it is surely no accident that the first piece of music which Stravinsky admitted he had written was a setting of The Lord’s Prayer in Latin, and the piece he was working on when he died was a setting of The Lord’s Prayer in Russian.

He had seen Tchaikovsky conduct. ‘I saw a man with white hair and large shoulders,’ he told me. ‘Tchaikovsky’s death two weeks later affected me deeply, but seeing Tchaikovsky that night in the Mariinsky Theatre has remained fixed on the retina of my memory all my life.’ And yet he outlived The Beatles whom he had expressed the wish to meet, so in every sense he bestrode the 20th century with a purpose and conviction of titanic proportions.

As for that second phone call … Making the film in 1980-81 had not been easy. At that time, to make any film in the Soviet Union required a ‘co-production’ agreement with Gosteleradio, and permission for anything related to a Russian musician, alive or dead, ultimately passed through the office of the General Secretary of the Composer’s Union in Moscow, Tikhon Khrennikov. And thus, over another tea, vodka and sweetmeats, a meeting took place between myself and Khrennikov. For over 30 years, this bureaucrat (and sometime composer) had dominated Russian musical life. It was he who had sat by Zhdanov’s side as Shostakovich had been publicly denounced and the manuscript of his Ninth Symphony torn up in front of him at a special congress in 1948. It was he who had advised the Politburo that Prokofiev’s music was decadent and had thus made the composer’s life a misery. And it was he who had ensured that Stravinsky’s music was rarely performed throughout the Soviet Union.

We sat together at a long table, with only our interpreters. He, inevitably, sat at the head. I cannot now believe that he didn’t realise I knew who he was and what he had been responsible for. Yet he sat there beneath three portraits, which he proudly indicated to me. To the left Stravinsky; to the right Prokofiev; and above him, Shostakovich. As it turned out, however, it was Khrennikov who made possible most of my requests: ballet at The Bolshoi, access to Stravinsky’s Russian cousins (with one of whom I later fell in love), and most memorably a visit with Robert Craft to the Sorotchintsy Fair in Ukraine which Stravinsky had been to many times as a boy and which was as much an influence on what became Petrushka as the Shrovetide Fairs in St Petersburg. In fact, after we had filmed an extract from Petrushka with dancers from The Bolshoi, the ballerina came to me with a bunch of red roses and a very big kiss, thanking me, over and over. I told her the privilege was mine. No, no, she replied. They had had to learn the part of the ballet I needed especially for me (they knew the music, of course) ‘because it was not in their repertoire!’ I was shocked. They were exhilarated.

The only request that Khrennikov turned down was a visit to Stravinsky’s only home he had owned with his first wife and cousin, Ekaterina, at Ustilug in what is now Western Ukraine. He was adamant. Permission would not be granted. Twenty years after this came the second phone call. Did I have Robert Craft’s address? ‘Possibly,’ I said, ‘but before I write to Craft I need to know the nature of the enquiry.’ My correspondent, it transpired, represented the region of Vlodymyr-Volyn in which was situated Stravinsky’s old house at Ustilug. The house stood in the land and vast estate once owned by Ekaterina’s family, the Nossenkos. It had fallen into disrepair but had now been faithfully restored by the regional government and they wanted Craft to come and cut the ribbon at the opening ceremony.

I duly wrote to Craft and received a rather succinct and instant reply. ‘If you think I’m going to that God-forsaken country ever again, think again!’ In fact, Craft had enormously enjoyed his visit with me back in 1981 and written about it extensively in his published Dairies, especially noting that one night when we were lost en route to Poltava we were kept alive by biscuits specially baked for such an emergency by Vera Stravinsky herself. But Craft had a point. To get to Ustilug today involves a flight via Warsaw to Lvov, followed by a four-hour journey by bumpy road, mostly bereft of clear signposts, to somewhere accurately described by Craft as being in the middle of nowhere. Except that it was on the border of both Poland and Belarus, and in 1981, as I now understood, would have been bristling with missiles pointing straight at London, hence Khrennikov’s refusal to let me anywhere near a military zone.

So, no Craft to cut the ribbon. Who else? There was Milène, the Maestro’s second daughter, was still alive and living in Los Angeles, but aged 94 she was too frail to travel those bumpy roads. Eventually Craft suggested that I should go, if only for a recce so that I could report back on what had been done in Stravinsky’s name. What I found astonished me. On very limited resources – Western Ukraine is not exactly flush with money for projects about someone most of them had no knowledge of whatsoever – the house had been beautifully restored, and filled with objects and furniture which although clearly not the originals had the right smell and feel. The Museum has since been open to the public, and despite being in a truly remote area, attracts a steady stream of pilgrims. Given that Stravinsky’s only other house which he owned in his entire life at 1260 North Wetherly Drive in Hollywood just off Sunset Strip has now been extensively rebuilt, the house in Ustilug is unique. And, what is more, together with the nearby town of Lutsk, the area now stages an annual Stravinsky Festival, the only such worldwide. And I have been privileged to be invited at their expense every year.

So you see: two phone calls which changed my life. How lucky I have been, especially to have spent some time with one the greatest creative artists I am ever likely to encounter. Thinking about what to call my film, I settled on: ‘Once, at a border …’ Stravinsky had told me, ‘Once, I don’t know where it was, at one of the borders, I presented my passport. “What is your occupation?” asked the Customs Officer. “It’s written,” I replied. “It says composer of music,” he said. “No, no,” I replied. “Not a composer of music. I am an inventor of music. Invention is not forced; nobody forced me to invent. I could easily make commonplace music, which I know exists. It exists much more than good music. But commonplace music does not need to be invented.’

‘The activity of composing is everything for me,’ Stravinsky told me fiercely. ‘It is for that that I live. I like to compose music, much more than the music itself. I am at ease in the difficulties of composing, even the difficulties. But I can wait. I can wait as an insect can wait. I am somebody who is waiting, all my life.’

Later, he remarked: ‘I speak Russian. That you hear in my music. I am Russian.’ It was as if there was nothing more to say about himself or his art. Throughout its many vicissitudes and apparent changes of direction, this Russianness burned through everything he did. It doesn’t explain everything, perhaps, but it was the bedrock upon which all else was founded.

Tony Palmer’s Stravinsky 50th anniversary box-set, comprising the original documentary on DVD, two CDs (28 tracks) of music recorded for the film and a 28-page brochure featuring 100 photos, many of them never seen before, is on sale from April 6; to order your copy, visit Tony Palmer's website

Gramophone has collaborated with Tony Palmer to offer a fantastic competition for our readers. First Prize is the anniversary box-set, while 10 runners-up receive a copy of double CD. Simply enter by clicking here