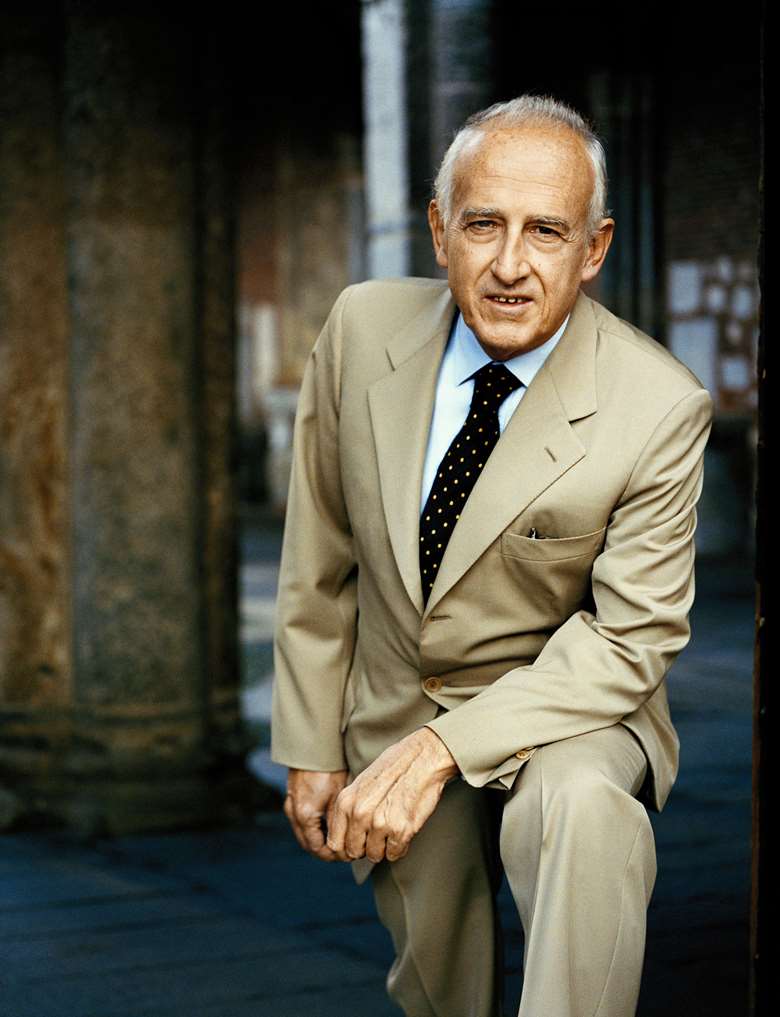

Maurizio Pollini – Interview (Gramophone, February 2002) by Bryce Morrison

James McCarthy

Thursday, March 29, 2012

Talking to Maurizio Pollini can make one apprehensive. He has a reputation for diffidence, shyness and an understandable reluctance to speak openly about his life and career. Like others before him he feels his truest biography lies in his playing; that verbalising his thoughts and feelings is a superfluous activity. Then there is that formidable, analytical mind to consider, something that has fuelled controversy over the years. For some he is, quite simply, ‘the world’s greatest pianist’ while for others he merely offers a ‘steel-fingered X-ray picture of the score’. Richter’s candid comments in Bruno Monsaingeon’s Sviatoslav Richter: Notebooks and Conversations (‘the style of playing is powerful and no doubt even “heroic”, it’s all perfectly correct and virtuosic, but lacking in any kind of charm, dressed up in the latest fashion as though on purpose.’ Later there are sniping references to ‘Chopin cast in metal’ and ‘Chopin with well-developed biceps’) strike a false note with Pollini’s admirers who turn instead to ‘an elegance, clarity, and lucidity that are specifically modern’ (New York Times magazine); and to ‘performance[s] of the most phenomenal precision and acute expressive poise, every note precisely weighted, coloured, above all felt’ (Gramophone).

Now, the picture has altered. Pollini is in a giving vein, genial and relaxed after his more than successful Royal Festival Hall recital of November 20. ‘I have a special love for London audiences. They are so attentive, as silent and rapt (I don’t think they were sleeping) in Stockhausen and Webern as in Brahms and Beethoven. I know such a mix can intimidate some people but I am determined to present the best music of our time, to keep the flame burning.

‘The situation is difficult for young artists,’ Pollini continues, who are not encouraged to explore and experience the age we live in, to realise that music of a different if often difficult language can be just as rewarding as great works of the past. Many of them only play contemporary music out of a sense of duty rather than love or comprehension and that saddens me greatly. They need to devote more time to the great post-Bartok and Stravinsky works and there are, after all, some relatively easy options, less demanding than, say, Boulez’s Second Sonata. It is true I am uncomfortable with what might loosely be called neoromanticism, but it is not true that I dislike Rachmaninov. In common with all young pianists I came under the spell of Horowitz playing the Third Concerto but I remain happy to listen to rather than perform such music.’

So how does he feel about turning 60 – time to reflect on the past? ‘I am a present-and-future person, only momentarily given to reflection or nostalgia. Of course, my success when I was 18 in the 1960 International Chopin Competition in Warsaw was a turning point and a red-letter occasion. Imagine being made a fuss of by Rubinstein who was on the jury and who was more than kind. This was a heady experience for a teenager.

Of course, there are dangers in such early exposure and acclaim. On the one hand you need to be heard, on the other you must evolve naturally, must not rush and lose your sense of awe and wonder. But I think it is very important to play great music when you are young, to make music such as Beethoven’s Op 111 Sonata or Brahms’s Second Concerto a mental and physical part of you at an early age. Otherwise you run the risk of insecurity later in life. Chopin’s 24 Etudes, which I performed publicly when I was 14, need to be studied as soon as possible if you are to avoid later stress, so that you are free to reach out and capture the poetry beneath the surface of such outwardly pragmatic or technical music. Ideally, things have to be not too late but not too soon and that is why I took a lengthy sabbatical soon after Warsaw in order to consolidate the qualities that would nourish and sustain me over the difficult years ahead.’

And how does he feel now that he sits on the other side of the jurors’ bench? ‘I am closely associated with a competition specialising in contemporary music, but judging can be a tricky business. It’s difficult to listen with absolute objectivity. What can you tell in, say, one hour’s performance? You start to wonder about their potential as well as their present achievement. You tell me about a Russian jury colleague who marvelled over a performance of a Prokofiev Sonata radically different from preconceived notions of the great Russian tradition of, say, Horowitz, Richter and Gilels. And that is both unusual and reassuring; part of an awareness of the miracle of music, its capacity to constantly renew itself.

‘My teachers were very helpful but I have to agree with Rubinstein that some of the best instruction comes from listening to one’s own recordings. I was also lucky enough to grow up in Milan where it was possible to hear and learn from all the greatest artists. I have such memories of Rubinstein’s Chopin and also of Wilhelm Kempff, a great poet of the piano. He had what I should call a Goethian view of Beethoven, a beauty and wisdom all his own. At the same time I would agree with Schnabel when he spoke about music that is always better than it can be performed.’

But back to the present. DG is celebrating his birthday with ‘The Maurizio Pollini Edition’ which includes Pollini old and new. ‘It contains some of my most recent recordings and Chopin’s First Concerto from 1960 [recorded in the wake of the Warsaw Competition], the happy time of my first visit to London. Naturally, I listen with interest, liking this, disliking that and sometimes feeling that things could be different if not necessarily better. My future plans include recordings of the First Book of Bach’s 48, possibly Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit and, of course I shall continue my journey through the Beethoven sonatas.

‘I’m not sure how to comment on a colleague’s description of me as a “moral” pianist, but it is true that I look for and try to uncover what seems to me the essence of a work, its truth. And I suppose in that sense I am a pianist of my time.’

Back to Maurizio Pollini / Back to Hall of Fame