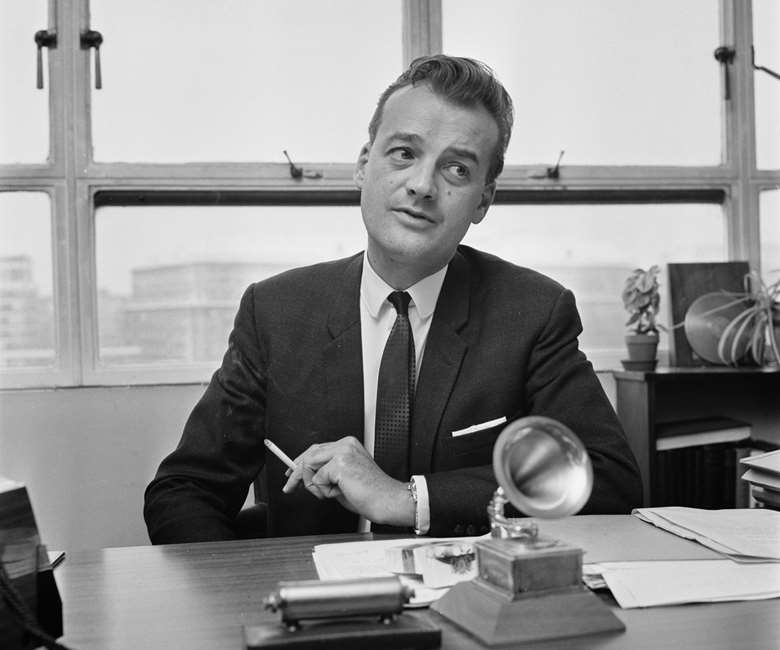

John Culshaw at 100: Record Maker

James Jolly

Friday, June 14, 2024

As Decca marks the centenary of one its most visionary producers, James Jolly hears from John Culshaw’s friends, colleagues and admirers in celebration of one of the classical record industry’s greats

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter