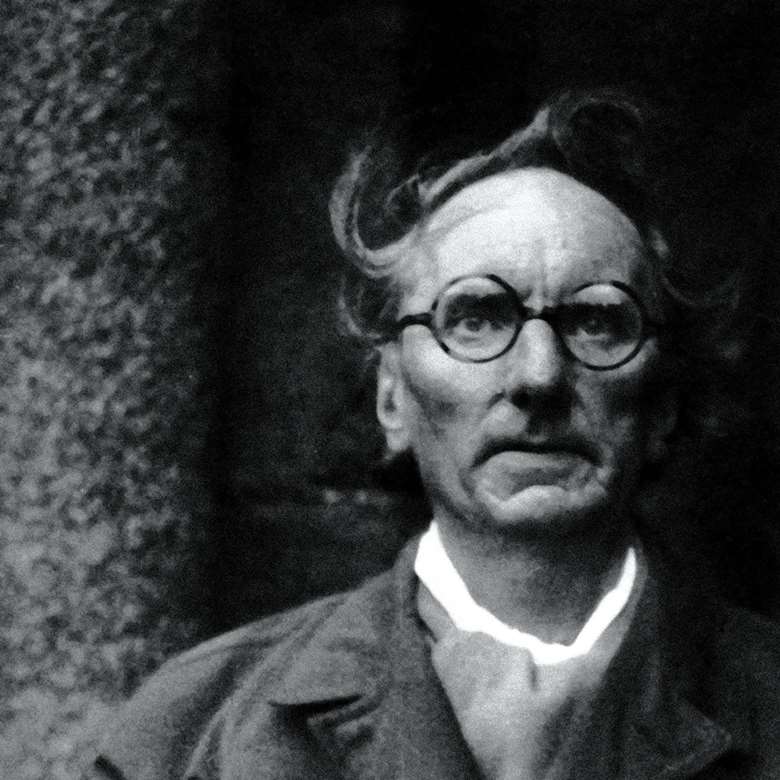

Introducing your next great musical discovery: Rued Langgaard

Andrew Mellor

Thursday, September 25, 2014

Andrew Mellor offers a guide to the Langgaard's 'singular reimagining of music’s parameters of time and space'

At this year's Gramophone Awards the Nightingale String Quartet won the Young Artist of the Year Award principally for their recordings of Langgaard's String Quartets for Dacapo, and this Saturday (September 27) sees the UK premiere of Langgaard's Fourth Symphony in London. Andrew Mellor introduces the Danish composer's very special sound world...

At a meeting of European composers in Stockholm in the late 1960s, the great Hungarian modernist György Ligeti announced to the assembled minds that he considered himself ‘a disciple of Langgaard’. It would have revealed a good deal about Ligeti’s musical world-view – his singular reimagining of music’s parameters of time and space. But instead it left the room rather baffled. Nobody had a clue who Langgaard was.

If one or two did know of him, they’d doubtless have tittered at Ligeti’s remark. Rued Langgaard had been a standing joke in Danish music; a loner, a freak and an outcast. Of his 16 symphonies, seven string quartets, numerous miscellaneous works and an apocalyptic opera, Antikrist, none were commissioned and half were never performed in his lifetime. While he trod this earth, Langgaard had no mentors, no pupils and few admirers. His troubled relationship with the Danish cultural establishment fluctuated between enthusiastic pleading and vitriolic anger – the latter often in musical form.

Ideologies strange and pressing forced Langgaard into serious creativity from the age of 11. He railed against the spiritual state of the world and the reversal (as he saw it) of musical progress. But his creations sprang from emotional prompts, too: his isolation, his religious fervour and what we can fairly assume was the torture of mental illness. Works of gregarious and liberated joy are the inevitable peaks against his troughs of depression and anger. Snobbery and circumstance might have trampled on Rued Langgaard, but they lent his music a strange, variegated urgency and power in the process.

Langgaard did experience major success – once. Aged 19 he had his astoundingly assured First Symphony inaugurated by the Berlin Philharmonic under Max Fiedler. It proved, in the words of the composer’s biographer Bendt Viinholt Nielsen, ‘the climax of his whole career’. War then tore through mainland Europe and by the time it was over Denmark had its musical figurehead – man of the people Carl Nielsen. Langgaard’s lofty visions of music as the father of both politics and religion felt awkward and aloof. Nielsen, for Langgaard, became the embodiment of the problem.

But it didn’t stop Langgaard writing. From a loosely post-Romantic basis, his voice shot off in an array of hyperinnovative directions just as frequently as it sought refuge in old certainties and disciplines. The First Symphony rides the crest of Straussian orchestral craft; the 15 that follow leap both forwards to minimalism and experimentalism and backwards to traditions past. While Nielsen’s Inextinguishable was drying on the page in 1916, Langgaard was hatching plans to instruct a solo pianist to knock on the woodwork of the instrument and strum its strings in Insektarium,his fantastical depiction of mystery critters. When the Inextinguishable was eventually recognised as the apex of Danish symphonic thought, Langgaard reacted with a homage – the anxious, energy-harbouring Sixth Symphony. When Nielsen was posthumously commemorated in a 1948 biography, Langgaard spawned the spoof cantata Carl Nielsen, our great composer, to be sung ‘with all possible force’ and ‘repeated for all eternity’.

If those gestures tell us anything about Langgaard, it’s that he viewed his art as a means of communication across the board – from expressing visions of the divine to playing out petty spats. Langgaard wasn’t a dabbler or an academic, he was an obsessive and a dynamo. Shunned and ultimately exiled far from Copenhagen, music was all he had. His finest works wed exceptional craft to palpable expressive need. They contain some of the most unusual musical textures of their age, yet rarely sound contrived. In the greatest litmus test of all, they leave an emotional residue that approaches the Mahlerian.

That might be a rather personal assessment, but in that sense it’s also irrefutable. Langgaard has been the biggest surprise-discovery of my musical life, exploring his oeuvre akin to stumbling upon a second Barber or Martinů. The music never fails to surprise: from the far-flung, spinning sonorities of his Music of the Spheres (not, for me, his masterpiece) to the tautness of his Fourth Symphony – its poise incomparable, Brahmsian twists in colour and mood seen as if through a kaleidoscope of late-20th-century irreverence.

On one level Langgaard has become an icon of injustice. His lack of success remains chilling, despite its self-perpetuation. Denmark’s diverse contemporary music scene might have learnt some lessons from that, but now we must judge his music on its own terms. And for all the big gestures at play therein, it’s a simple choral song to which I often return to validate my own discipleship. In Høstfuglen, Langgaard sets a text by Herman Wildenvey for four voices. It’s all here – the delicate melodic gift, the exquisite distribution of material, the distinct mood within a few bars, the visionary technical effects. But there’s something bigger underneath it all: Langgaard’s ability, with all those facets in play, to distil his ideas right down to music of the most lucid simplicity and touching sincerity. For a moment I think of Mozart. But I soon snap out of that, and think only of Langgaard.