Icons – Stephen Kovacevich

Gramophone

Monday, March 21, 2016

Geraint Lewis pays tribute to a true ‘pianist’s pianist’ and a complete musician – one who is as much at home on the podium as he is at the keyboard

When Stephen Kovacevich now walks on to the platform, he cuts an enigmatic, white-haired and diminutive figure who smiles shyly before turning to the keyboard. He doesn’t look remotely in his 75th year and his playing belies any impression of such age. When he closed this 2015’s BBC Wigmore series with Berg’s Sonata, Op 1, it was noted that he made his Wigmore debut with this work as long ago as 1961, when he was 20. But that wasn’t merely a Wigmore debut as much as his European concert debut, full stop – and it immediately catapulted him to international acclaim at the very start of his career. Over the extraordinary course of Kovacevich’s journey our perceptions of Berg’s early Sonata may well have mellowed, but this is a pianist who does not ‘go gentle’ into a mellow old age – his wisdom and experience have naturally deepened and accordingly he remains uncompromisingly committed to finding the depth and profundity in any music he plays.

The course of that journey saw him starting out as plain Stephen Bishop from California, who’d come to London aged 18 for lessons with the legendary and universally loved Myra Hess. There was a brief flurry of controversy in the 1970s when he announced suddenly that he would become Stephen Bishop-Kovacevich for a time, with the ultimate intention of dropping the Bishop altogether. This was in acknowledgement of his father’s Croatian heritage and his own deeply felt identification with the Central European tradition that lay at the heart of his musical experience. And the transition to Kovacevich was accomplished so seamlessly that the Bishop just melted away naturally – surely in part because this ‘pianist’s pianist’ remained true to his inherent strength of probing the music with integrity without any need of extraneous distractions or celebrity flim-flam.

It would perhaps be apposite to say of Kovacevich – as Sibelius did of his Fourth Symphony – that there was ‘absolutely nothing of the circus’ about him. This work happens to be one of his favourite scores and he has frequently conducted it with many major orchestras. Yes – Kovacevich, very much as the ‘complete musician’, started conducting in the early 1980s, and not merely in terms of directing concertos from the keyboard, though he did that superlatively too. It is a great shame that this aspect of his career was not exploited as fully by record companies and promoters as happened with contemporaries such as Barenboim and Ashkenazy. But I recall a concert with the London Mozart Players when Kovacevich conducted the finest live performance I’ve ever heard of Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony (with all repeats) as well as the most exciting of Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto, in which soloist and orchestra were miraculously as one.

One suspects that Kovacevich is perfectly philosophical about the varied paths taken by his career in an era when image often matters much more than insight. He has a wry turn of self-deprecating humour as when (again in his recent Wigmore broadcast) he stopped after a bit of bother in the finale of Schubert’s late, great A major Sonata saying: ‘I think I’ve just taken the wrong turning – going to Glasgow instead of Edinburgh!’ and then played the movement again, impeccably.

Schubert is one of those select composers with whom he shares a rare quality of understanding, amounting at times to communion. He has spoken vividly of the way in which the slow movement of that same A major Sonata suddenly collapses into a nervous breakdown and in concert in Cardiff this May he re‑enacted this experience – but as if encountering it for the first time. The fragility in the music emerged with that air of improvisation which the score itself can only convey in part. At another concert in an ancient church in North Wales nearly two decades ago I recall a moment in the slow movement of the B flat Sonata when that net of intimate communication between composer, performer and audience (Benjamin Britten’s ‘holy triangle’) became momentarily tangible and time magically stood still, until a cough broke the spell. On mentioning this to him afterwards he smiled: ‘Yes, I felt that moment too – you can’t will it, but when it happens…wow!”

In partnerships with Sir Colin Davis and Wolfgang Sawallisch in particular, Kovacevich has left a legacy of concerto recordings – Mozart (K467 and 503, far too few!), Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms (twice), Grieg and Bartók – and a second Beethoven cycle self-directed with the Australian Chamber Orchestra – which come as close to an ideal as is humanly possible. His Beethoven Diabelli Variations (both early and late) and the complete sonatas, as well as special examples of Bach, Chopin and Schubert, enshrine the self-effacing authority of a master who comes top of the pile for so many listeners who put the music first and the messenger second.

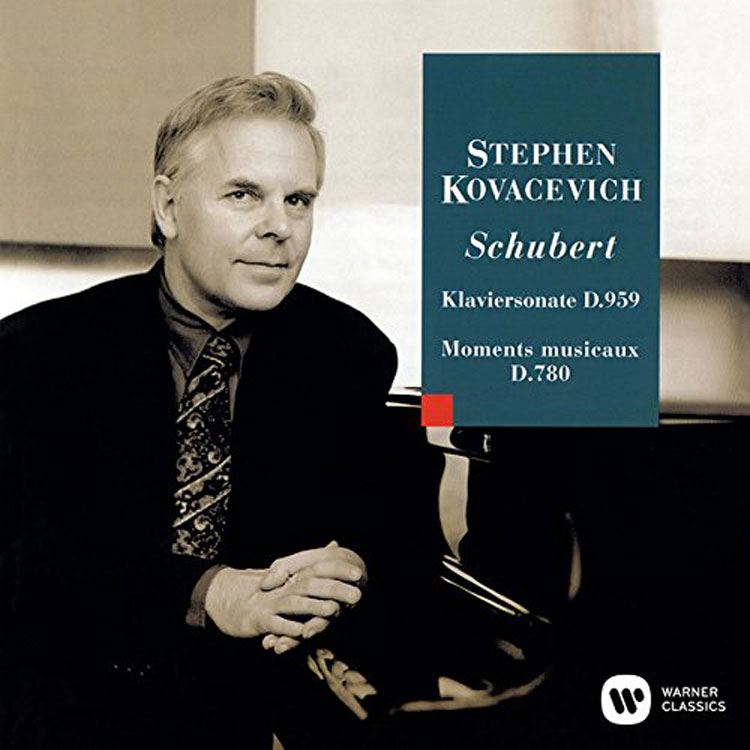

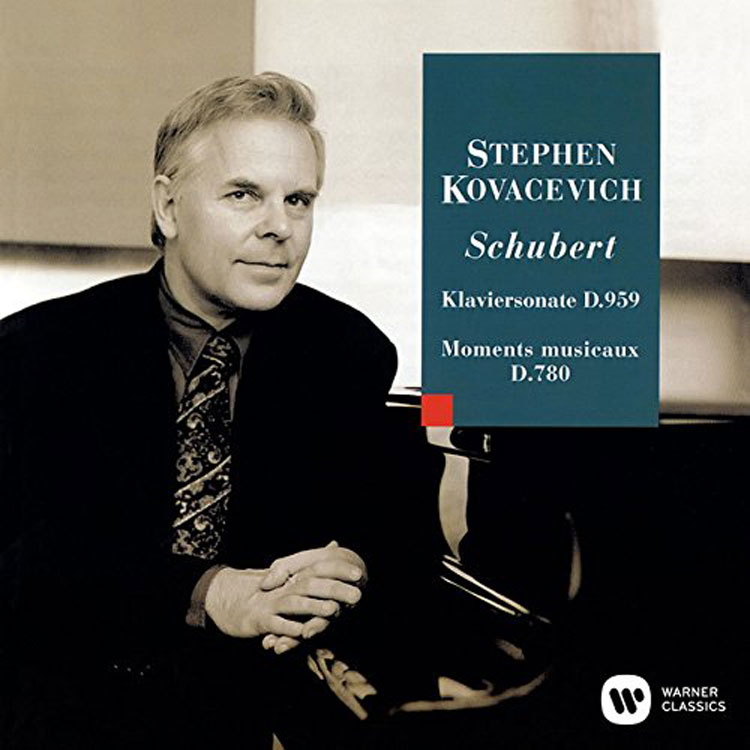

Key recording

Schubert Piano Sonata No 20, D959. Moments musicaux, D780

(EMI/Warner Classics)

Defining moments

1951 – Early promise

Makes concerto debut in his native San Francisco, aged 11, playing the Ravel G major and the Schumann

1961 – Landmark debut recital

European concert debut at London’s Wigmore Hall

1970s – Bishop becomes Kovacevich

Announces intention to change his surname from Bishop to Kovacevich

1978 – At the piano with Argerich

Duet recording with personal and professional partner Martha Argerich

1984 – Takes up the baton

Conducting debut with the Houston Symphony

1993 – A triumphant return to Brahms

EMI recording of the Brahms’s First Piano Concerto with the LPO and Sawallisch wins a Gramophone Award

2015 – Birthday celebration

Returns to the Wigmore Hall to mark his 75th birthday