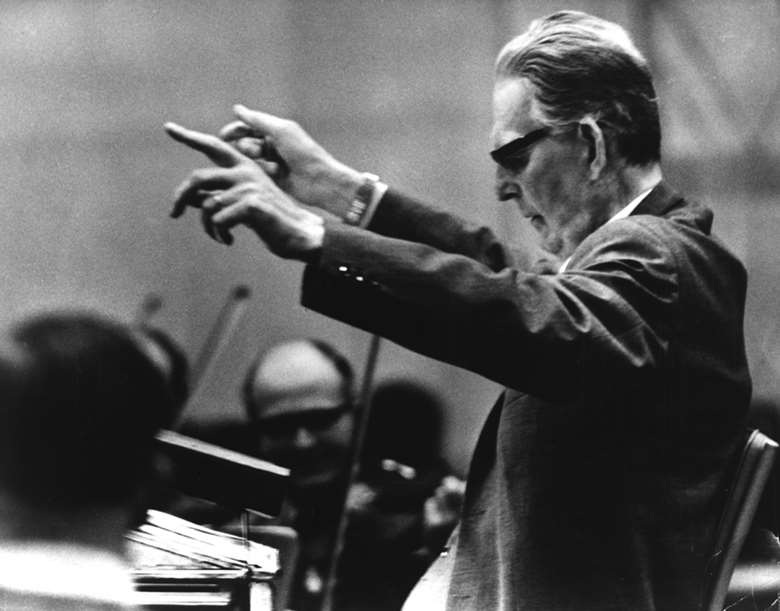

Icon: Otto Klemperer

Peter Quantrill

Wednesday, July 6, 2016

Peter Quantrill pays tribute to a conductor who owed his early career to Mahler and went on to become one of the most influential conductors of the 20th century

Making sense of Otto Klemperer the musician through his recorded legacy is more than usually like looking down the wrong end of a telescope. The image of the conductor as Moses, gaunt and unyielding, derives largely from the last decade of Klemperer’s long and chaotic life. His story could be said to begin and end with Mahler, the conductor as much as the composer. The wonky gait of Kapellmeister Mahler in Cologne provided Klemperer with his first memory. As a young tyro he assisted at an early performance of the Second Symphony and prevailed upon Mahler to write a card of recommendation ‘which opened all doors’. Klemperer kept it on his person ever afterwards and returned to the older man’s music both in his own compositions, written during the manic periods of the bipolar disorder that afflicted him all his life, and in performances, especially of the Second Symphony.

‘Steht alles in der Partitur [It’s all in the score]’, wrote Mahler and it should be in this light (coloured by the 19th-century Romantic culture in which artists took ownership of works) that Mahler’s retouchings of Beethoven should be understood, and indeed Klemperer’s use of them. Every generation claims its own special access to a new kind of textual fidelity in order to find its own accommodation with the unresolvable paradox of working with dead men’s material while belonging to the here and now, breathing new life into old testaments.

Back in 1924, Wolfgang Stresemann noted of a concert with the Berlin Philharmonic that ‘his approach stood in almost diametrical contrast to those of Furtwängler and Walter. It was less concerned with expression and feeling. At the core of his interpretations stood form, structure and a relentless determination…to provide an objective realisation of the score.’ A key phrase in this testimony is ‘concerned with’. Klemperer doesn’t underscore the pathos of the ninth symphonies of Dvořák and Mahler, not because such feeling is foreign to the work but precisely the opposite, because it inheres within each bar. The music does the expressing, not the conducting. On the face of it, this looks like an article of faith for most 20th-century musicians, including practitioners of the historically informed performance movement, but Klemperer was far more influential upon the conducting of Pierre Boulez. Klemperer’s legacy has yet to be ramified, but any examination of it must surely focus on the shape of the house and not the brickwork: ‘Better you play wrong notes, but in time,’ we can hear him (on Archiphon ARC-WU042) genially yelling in 1942 to a New York youth orchestra who appear to give him no other choice while rehearsing Brahms.

Decades later, as intendant of the BPO, Stresemann issued a return invitation to Klemperer, who had become the darling of Philharmonia audiences in London, but what he called the conductor's ‘non-espressivo’ approach clashed with the orchestra’s corporate identity now that it had been overtaken by Karajan (as you can hear on Testament). Times had changed, and yet Klemperer had not. Just as a Beethoven Fifth in New York in 1926 was greeted by a local critic as being ‘on a scale of sonorous tonal grandeur as yet not surpassed’ but also unpolished, these qualities were still evident in the marmoreal last symphony cycle in London in 1970, preserved by BBC television and available on YouTube.

In a sense, EMI’s recordings allow us to hear a ‘true’ Klemperer, one that didn’t always emerge in concert because of the vagaries of his mood and rehearsal availability. The sad lack of recorded testimony to Klemperer’s revolutionary work at the Kroll Opera House in Berlin (1927-31), beyond a few excerpts and orchestral pieces, only enhances the value and interest of the six complete operas left to us from his time in Budapest (1947-50). In their breathless intensity and yet breadth of understanding, Lohengrin and Così fan tutte especially show us the man who took Berlin by storm in the 1920s.

Secular rites took on talismanic powers throughout the career of this sceptical Jew-turned-Catholic-turned-Jew: not only Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony but also Mozart’s Masonic Funeral Music and Beethoven’s Ninth, and most of all Fidelio, live recordings of which (in Budapest and London) triumphantly embody what his biographer Peter Heyworth called Klemperer’s ‘almost Mahlerian clarity of texture’. If that appreciation sounds odd, it is because we are the ones out of time. ‘We should now atone for all that was done against Mahler,’ remarked Aladár Tóth, then director of the Budapest Opera, remembering how the young Mahler had been driven in 1891 from his directorship of the opera by political machinations. It was Tóth who secured Klemperer’s services and defended and protected him against criticism, personal scandal and penury. ‘After all, Klemperer is his greatest heir.’

This article originally appeared in the July 2013 issue of Gramophone magazine. To find out more about subscribing to Gramophone, please visit: magsubscriptions.com