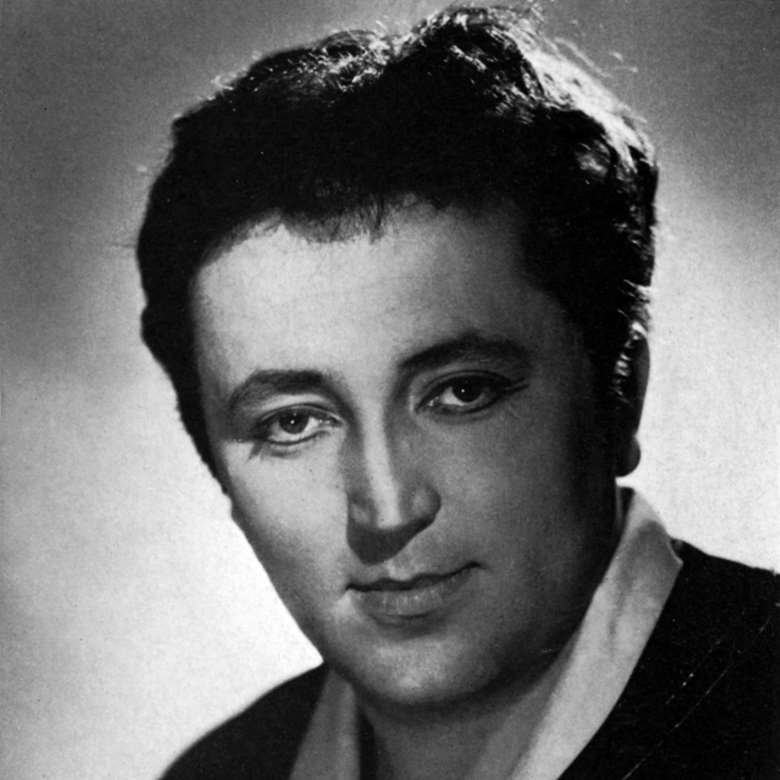

Fritz Wunderlich, a profile by Richard Wigmore (Gramophone, February 1999)

James McCarthy

Thursday, May 9, 2013

When Fritz Wunderlich died from a fall in September 1966, aged 35, he was mourned as the greatest German lyric tenor of his generation, and the only true successor of Richard Tauber and Peter Anders. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau spoke for many when he described Wunderlich as being, 'quite simply, in a class of his own.' His sensuous, ductile voice, so freely and naturally produced, had no trace of the grittiness commonly found in German tenors. This, combined with his liquid legato and his intense, innate musicality, made him a Mozart singer in several million. Yet his repertoire ranged wide. He was equally at home in Bach, Verdi and Richard Strauss. When he sang the title-role of Pfitzner's Palestrina in Vienna he was compared, not unfavourably, with Patzak – the ultimate Viennese accolade. And, virtually alone among tenors of his day, he moved uninhibitedly from serious to lighter repertoire, singing operetta and popular songs with relish, yet without kitsch or vulgarity. His stunning, all-or-nothing Granada, with high Cs to kill for, has long been a favourite on BBC Radio 2.

After a hard childhood (his father, a military bandmaster, was persecuted by the Nazis and committed suicide just after the boy's fifth birthday), Wunderlich won a place at the music college in Freiburg in 1950, studying both singing and French horn. (He was later to attribute his phenomenal breath control to his horn-playing days.) His first big successes both came in his last year at college, 1954: as Tamino in a student production of Die Zauberflöte, and as Jan Janicki in Millöcker's Der Bettelstudent at the Freiburg Opera House . He was immediately auditioned for the Stuttgart Opera; and despite repeatedly cracking on the high notes in Tamino's Portrait Aria (!), he got the job, and was on his way.

Wunderlich's complete opera recordings are frustratingly few, partly because, while he was under contract to Electrola (German EMI) from 1959 to 1964, several of his key roles were already ear-marked for Nicolai Gedda and Luigi Alva. An Electrola Bartered Bride (in German), conducted by Kempe, reveals his engaging sense of fun. Even more valuable is a live Munich Traviata – sung, exceptionally, in Italian – under Patane (Orfeo), with the young Teresa Stratas as Violetta: Wunderlich 's Alfredo, tender, romantic, impetuous and gloriously phrased, has been likened to Gigli's, a comparison that, for once, does not seem wide of the mark.

It was only after he moved to DG in 1964 that Wunderlich began to feature regularly in major opera sets. His Leukippos in Böhm's Daphne, recorded live in Vienna in 1964 (DG, 11/94), achieves the near-impossible in distilling fervent lyricism from Strauss's sadistically taxing lines. Such a role points, again, to what might have been. Wunderlich was being wooed by Karajan and Wieland Wagner to take on Froh and Walter von Stolzing. He resisted, saying, with tragic irony, that a tenor needed to nurture his voice carefully up to the age of 35. But if he had lived, he would surely have tackled these, along with such roles as Florestan and Max in Der Freischütz.

But to the end Wunderlich's core operatic repertoire remained Mozart: Don Ottavio, Ferrando, Belmonte and Tamino. His Belmonte, both with Jochum (DO) and in a live 1965 Salzburg recording with Mehta (Orfeo), and his Tamino in the famous Böhm recording are arguably his greatest achievements on disc: less graceful, perhaps, than Leopold Simoneau, his finest immediate predecessor in this repertory, but more ardent, more heroic (a thrilling ring to the tone, for instance, at the close of Tamino's Portrait Aria) and more varied in colouring.

Wunderlich sang Tamino – his Schicksalsrolle, or role of destiny – for the last time at the 1966 Edinburgh Festival. A few weeks later he died from injuries sustained in a fall at the hunting lodge of his friend Gottlob Frick, a premature loss to rival those of Dinu Lipatti and Kathleen Ferrier. The word that cropped up routinely in German obituaries was unersetzlich – irreplaceable. Several possible successors have been tipped. But, like the new Ian Botham in English cricket, the new Fritz Wunderlich has remained stubbornly elusive.

Click here to subscribe to the Gramophone Archive, featuring every page of every issue of Gramophone since April 1923