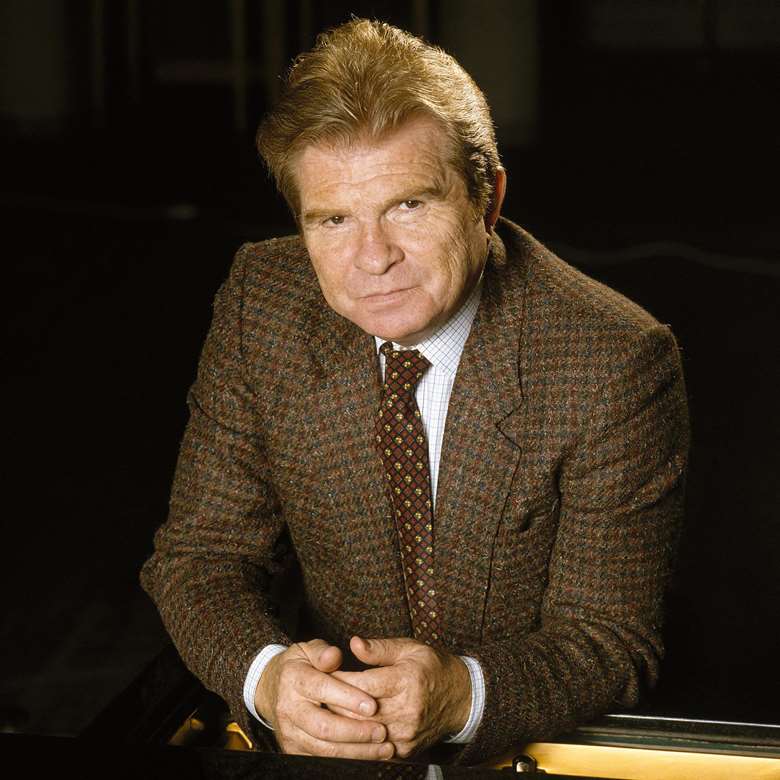

Emil Gilels, profile by Robert Layton (Gramophone, December 1985)

James McCarthy

Thursday, May 9, 2013

Among the great pianists of our day, Emil Gilels stands out as a giant among giants. In terms of virtuosity he was second to none, yet his leonine power was tempered by a delicacy and poetry that few matched and none has surpassed.

He was born in Odessa on October 19, 1916, and the news of his death in Moscow only a few days short of his 69th birthday brought much sorrow. He made his debut in 1929 and four years later carried off first prize at the Moscow All Union Contest with a sensational account of the Liszt/Busoni Figaro-Fantaisie. But he wisely remained in Odessa until coming to Moscow to study with Neuhaus. He was beginning to establish himself outside the Soviet Union, winning the Ysaÿe prize in 1938 and was engaged to play at the 1939 New York World Fair, when war intervened. For most people in the West, he remained a legend until the 1950s brought him to Europe.

What marked Gilels off from other pianists was not just his aristocratic polish (Richter has that too), or his commanding virtuosity, which in his case was a vehicle for deep musical insights, but his very special and totally individual tonal world, a characteristic of all great pianists, and a spirituality that shone through his greatest performances. I first heard Gilels play in Stockholm in the mid-1950s in the Third Rachmaninov Concerto. What I remember from that occasion, was not so much the virtuosity, though that was not in short supply, but rather the poetry and tenderness that were so much his own. As so often with Gilels, one was taken aback at the way in which he shaped a phrase or coloured his tone and the way he succeeded in conveying the impression that the piano had no hammers.

His appearances in England were all too rare, and nearly always memorable musical events. He had a quiet sense of humour which emerged when he was billed in one provincial English town quite recently as Emil Giles – and as if this were not enough, a photo of Fischer-Dieskau represented him. His response, when shown the handbill, was 'I no sing Winterreise!', though whether he really was amused is another matter! In the few conversations I was privileged to have with him he viewed with concern and some pessimism the state of music and of the world.

Although one thinks of him as a great interpreter of Beethoven and Brahms, his repertoire was wide-ranging and extended from Albéniz, Bartók, Debussy to Smetana and Saint-Saëns. His gramophone legacy is extensive, and collectors will not readily forget his Liszt Sonata and his Tchaikovsky B flat minor Concerto with Reiner, his magical record of the Grieg Lyric Pieces on DG (10/85) and the glorious Brahms concertos he did with Jochum (DG, 7/84), the dazzling account of Petrushka he gave at the 1973 Prague Spring Festival briefly available on Supraphon and, of course, his magisterial Beethoven sonatas – and in particular his Op 101, which to my mind remains unequalled (DG, 11/72). Those who heard his unforgettable performance of the Hammerklavier at London's Royal Festival Hall in February 1984 will recall that even when Gilels was storming its greatest heights, no fortissimo sounded percussive, strained or ugly.

I hope HMV will secure some of his Melodiya records from the 1950s such as the Franck Symphonic Variations and the Medtner G minor Sonata in spite of the poor recording. Medtner's Sonata reminincenza, whose wistful melancholy he captures so well is included in the invaluable HMV box , 'The Art Of Emil Gilelsl (4/84). EM! should follow this up with the Beethoven concertos he recorded in the 1950s, which have a greater humanity than the later set he made with Szell.

One of the characteristics of greatness in a composer is that he creates his own individual sound world, and the same yardstick applies to great interpreters, be they conductors, violinists or pianists. No pianist had a more distinctive or individual sound world than Emil Gilels. He had something of the wisdom of a Solomon, the tonal beauty of an Arrau, the intellect of a Schnabel and the spirituality of a Lipatti, and his death silences a unique voice in music.

Click here to subscribe to the Gramophone Archive, featuring every page of every issue of Gramophone since April 1923