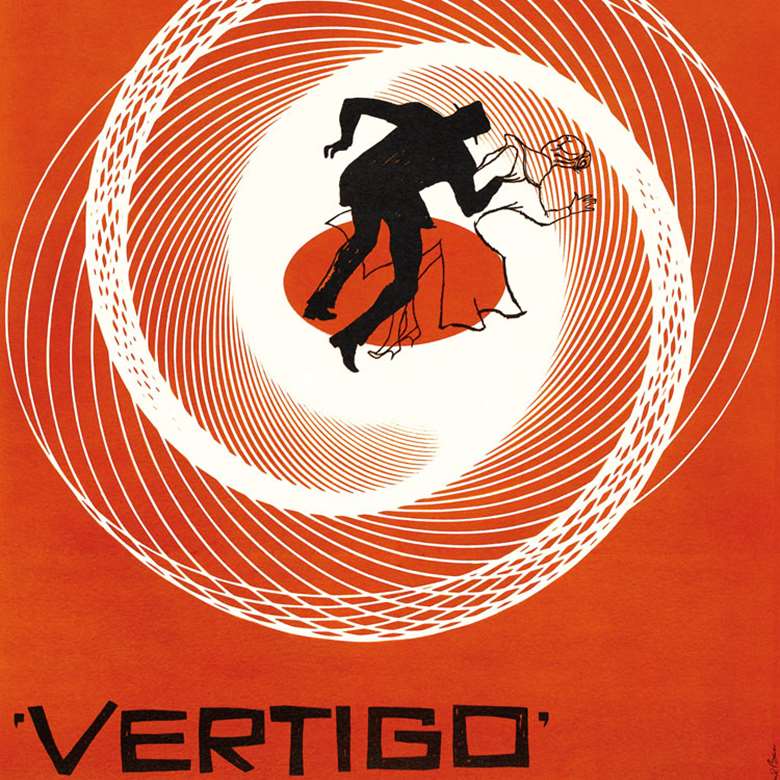

Debate: was Bernard Herrmann a great composer?

Gramophone

Monday, February 20, 2017

John Amis, Rumon Gamba and Adrian Edwards discuss the legacy of Hitchcock’s favourite musical collaborator

Adrian Edwards Bernard Herrmann said ‘I think that film music is an art and that films need music and music needs film’.

John Amis Well, I think it can be an art. I mean Prokofiev, Walton, sometimes Alwyn. Very often Herrmann can be an art. Certainly films need music as he said. If you run a film without the music it’s pretty awful.

AE Well, it’s very hard to think of some of Bernard Herrmann’s titles, particularly the Hitchcock ones, without music.

Rumon Gamba It only works as an art form in a lot of people’s eyes if it’s attached to the film. And I’m asked a lot of questions about how film music can survive in the concert hall away from film. And it’s been very interesting for me to deal with Herrmann’s music. Can it survive away from the film as Walton can? So, of course, in the context of a film it’s incredibly artful, but does it stand up on its own as an art form?

JA Well I don’t think that Benny (if I may call him that) ever thought of music as being something very special. He said it’s always part of the film, part of an art form. I don’t think he thought of it as an art form in itself though your quote seems to belie that.

AE So would you say that Vaughan Williams’s score for Scott of the Antarctic became a greater piece of music when it was transformed into a symphony?

JA Well, I don’t think it is a great piece. I mean I like it but I don’t think it’s a great piece, and the same with Benny’s music. I don’t think it’s great music, but it’s entertaining. I sometimes see a movie on the box and I think, hello, that must be Benny. I can’t always place it, it’s something to do with the harmony.

RG The scoring in particular. He was king of the ostinati.

JA And the scoring is fabulous. And it got more and more extravagant didn’t it? The piece that Hitchcock finally rebelled and said ‘no’ to, well I think the scoring started with nine trombones, 12 flutes, and 16 harps, or was it horns?

RG He’s done both!

JA I wonder if that score exists.

RG I think there are some snippets.

AE We’re talking about Torn Curtain.

JA Hitchcock’s last stand. He wanted tunes but Benny didn’t write tunes.

RG I suppose not in the traditional sense.

JA What Hitchcock wanted was something he could sell on a disc, as well as a film.

RG I think he wanted to take the art form further in a more modern way, both in the way he filmed it, and the way he wanted the music to sound.

The conversation moved on to juxtapose his film scores with his other music.

AE Writing film music is partly an art because you’re writing to a prescribed number of minutes, in segments, in sections, all the time. Yet when we recall what Herrmann considered to be the piece by which he would be remembered, the opera Wuthering Heights, that’s a sprawling work which really could do with a bit of the technique of film writing being allied to it.

JA I think there are a lot of film gestures and atmospheric gestures in it but I do think it’s the most boring piece. I didn’t want to condemn him without reconsidering it, so I listened this week to the last two acts and I do think it’s a bit like eating polystyrene and there’s such a lack of melody. Although there’s one good song in it, the rest is really rather feeble.

AE So Rumon, what do you think happened? The marvellous, dramatic music he wrote for film eluded him when it came to Brontë.

RG Of course he was working with a great writer, but he didn’t have the visual stimulus. That’s what he needed. He was involved in the process of making films, unlike a lot of the composers who would score it afterwards. So he was an active creative partner. Perhaps he didn’t have a creative partner for the opera. Suddenly he was let off the leash with no time limits, and I guess one thinks when you write an opera you have to produce something grand. He was quite romantic in that respect, in the way he approached music. He wanted to emulate the Romantic composers rather than bring everything into a tight shape.

AE Eugene Ormandy wanted to programme his symphony, but Herrmann turned him down because Ormandy suggested cuts. How far did his belligerent personality get in the way of his concert work being performed?

JA I think quite a bit. He really was a very irascible man, on a very short fuse. It was so embarrassing sometimes. He would shout at each of his wives and argue and it would usually end in cries of ‘How dare you?’

RG I suppose that character gave him integrity. He was so concerned never to do something he didn’t want to and write something he didn’t want to.

JA He could afford to do that.

AE His film music is on our screens so often, it’s on TV, it’s been revived in films by directors like Quentin Tarantino, that his other work really doesn’t get a look in.

RG It’s the strength of the films that make the music so known. Unfortunately, a lot of British film composers were writing for films that haven’t lasted the course. They look very old fashioned. When you’re comparing something like Citizen Kane to Hangover Square, both of which Herrmann scored, Hangover Square hasn’t been shown on television here for years, because it isn’t directed by Hitchcock or Orson Welles. It’s the strength of the director that often allows these films to be seen and the music to be familiar.

AE Is Hangover Square recognisably a Herrmann score?

RG Yes it is. He wrote a Concerto Macabre, as he calls it, for when the soloist in the film is playing his final concert and the place is burning around him. It’s a thoroughly good film about a musician who blacks out when he hears dissonant sounds. And when he blacks out he’s in a different consciousness and he murders people.

AE I suppose it’s one of the most touching aspects of Bernard’s life that at the end of it, he was rediscovered by a new generation of film directors and he went out on a career high.

JA After the humiliation of being turned down by Hitchcock it must have been a great solace to him, in fact I know it was, to have the admiration of these new wave directors like Martin Scorsese. I just love that Taxi Driver blues in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. It’s really haunting. And Benny could do that. He could do something with the harmonies and the instrumentation that could absolutely clutch at your heart.

RG And it’s interesting that, in a way, the melody doesn’t matter.

JA Well it’s good because he couldn’t write them!

RG Yet Hitchcock wasn’t interested after that. Herrmann did try to reconcile with him…

JA …but they never spoke to one another again.

AE Nevertheless, Herrmann’s music for Hitchcock’s films gives them another dimension, don’t you agree?

RG Absolutely I do. I presume also because he was involved at an early stage and perhaps the music could influence the shooting and vice versa.

JA I once asked him, are you ever asked by a director if this scene isn’t so good, can you save it? ‘All the time,’ he said. And it’s true music can paper over the cracks.

RG Absolutely, and he was a master of atmosphere. A lot of composers are, but the difference is that he didn’t have to do anything complex to achieve that. He used simple chords.

JA It suggests a different class from the average film. You are aware of that when you hear the sound. Mind you, he said that you shouldn’t be listening to the soundtrack, you should be enjoying the film or assessing or experiencing the film.

AE The special musical moments aren’t always in the obvious places in his films. I think Brian de Palma has cited Psycho as an example. When Janet Leigh is on the road, pursued by the police, the camera set-ups are few, ordinary and rather boring. It’s the music that makes it.

JA And when it does, it clinches. You’re not aware that somehow, emotionally and psychologically, you’re clinched.

RG That’s it, psychologically. That’s the thing that a lot of Herrmann fans will go on about. It’s the psychology of the music. It goes straight to the jugular.

JA Talking of Psycho, that noise in the shower scene – peep peep peep peep – where did he get that from? Do you know any precedent?

RG Well, who else would have the guts to score a film for strings only, in those days as well?

JA A brilliant idea.

RG Brilliant, but simple.

AE Do you foresee the day when his music outside the film scores might be given before a wider public and acknowledged as being on a par with what he wrote for the screen?

RG It’s unlikely. They’ll come out as curiosities because he’s got a big fan club round the world. And people would like to hear these pieces. But I don’t think they’ll be accepted into the repertoire, I’m sorry to say.

JA I agree.