Chausson’s Concert in D: a guide to the best recordings

Charlotte Gardner

Friday, January 24, 2025

No other work in the repertoire is quite like Chausson’s Concert for violin, piano and string quartet. Charlotte Gardner delves into a rich recording history dating back almost a century

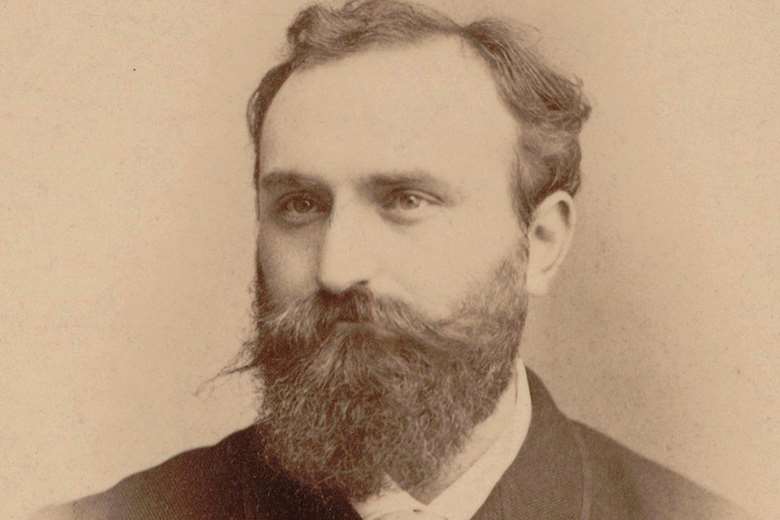

Can there be a more curious, category-defying beast within the chamber repertory than the Concert for piano, violin and string quartet, completed in 1891 by Ernest Chausson and dedicated to his friend Eugène Ysaÿe? Not a concerto, despite sometimes being mistranslated as such – both because a concerto requires an orchestra and because its inner scoring is too finely tailored to chamber conversation to be secretly nursing larger-scale aspirations. But also not a sextet, given that the strings don’t play as a single unit. So in fact genuinely a ‘concert’, as per the ‘harmonious ensemble’ translation of the word, operating as a sort of chamber-weight double concerto over which a pair of soloists engage with a string quartet ‘orchestra’ – albeit not an equally weighted double concerto, given that the piano’s panache-filled blizzards of notes are largely in accompaniment to the violin, much like another work dedicated to Ysaÿe that Chausson would play with him: the Violin Sonata by their mutual friend and Chausson’s beloved composition teacher, César Franck.

Essentially, this original work serves as a tantalising reminder of what the musical world lost when Chausson died in a cycling accident seven years later, aged just 44. Certainly it’s not hard to understand the instant success of its 1892 premiere in Brussels, Ysaÿe as soloist alongside pianist Auguste Pierret (stepping in at short notice after the originally billed pianist declared his part too difficult); nor why Ysaÿe himself loved and continued to play it for the remainder of his career.

It also appears to encapsulate Chausson himself. Born into a wealthy, highly artistically engaged family, Chausson trained first as a lawyer, then entered the Paris Conservatoire during his late 20s – in Massenet’s class, but soon switching to Franck – after visits to Munich and Bayreuth saw him swept off his feet by the music of Wagner. Stylistically, all three composers are audible across the Concert’s expressive, lyrical writing’s feast of striking harmonic and emotional twists and turns: Wagner in its luxurious textures, chromaticism and fevered drama; Massenet in its melodicism; Franck in its cyclical form and air of antique mysticism.

Emotionally, meanwhile, it bears a striking resemblance to the portrait penned of Chausson in the weeks following his death by the Paris critic and writer Camille Mauclair, one of the many leading artistic figures who frequented the Chausson family salon: ‘A grave spirit, his good cheer was often mere consideration for other people, and his peaceful manner concealed a soul deeply pained by the sufferings of humanity. He was a Christian, a mystic, with the most exalted understanding of life, forever mindful of the debt which his happiness imposed.’

Structurally, the Concert opens with an impassioned Animé – Calme – Décidé movement built on the ‘determined’ three-note motif heard at the opening of its slow introduction. An exquisite 6/8 Sicilienne follows, crescendoing from delicate intimacy to ecstatic rapture, its poised, Pas vite (‘not fast’) whimsical melodiousness an uncanny fit for Mauclair’s descriptions of the designs created for Chausson’s own living room, ‘in which graceful young girls mingled with the tracery of delicate trees in poignant poetry’ – the work of Henry Lerolle, his wife’s brother-in-law. Next comes a dark, chromatically snaking Grave, its sighing theme based on that of the Sicilienne, which builds from hushed beginnings to an anguished storm of a force and density far beyond the remit of a chamber work. The charged D minor Très animé finale then climaxes on a dramatic restatement of the very opening three-note motif, before closing on a triumphant D major shout.

Challenges and questions

Balance is perhaps the Concert’s greatest issue. The violin and piano soloists need to sound like principals. Chausson’s intricate textures also need to be heard, and while his inner part-writing has been much maligned (including in these pages!) for being dense and ‘overwritten’, it’s notable that when musicians genuinely honour his copious dynamic and articulation markings, the balance and lucidity issues fall away – almost as if he knew what he was doing after all.

Each movement is topped with a clear metronome marking, but it’s more up for grabs as to how far to take Chausson’s cornucopia of mid-movement calando/incalzando directions. He clearly wants time to hang suspended at points, but apply the brakes too much and you lose the architecture.

Finally, while most recordings opt for a permanent string quartet over ad hoc constellations, that’s not the only route to ensemble harmony. Indeed, the premiere itself was a halfway house, Ysaÿe performing with his Ysaÿe Quartet, which thus needed its resultant violinist gap filled by his student Louis Biermasz.

Between Friends

Appropriately, the Concert’s 1931 first recording features a pianist who once attended the Chausson family salon – Alfred Cortot, duetting tightly with his regular partner Jacques Thibaud and a fierily committed, apparently ad hoc quartet of violinists Louis Isnard and Vladimir Voulfman, viola player Georges Blanpain and cellist Maurice Eisenberg. Theirs is an intense, ardent reading, its crisp rhythmic momentum aided by their subtle, tautly managed ebb-and-flow approach to the tempo shifts. Thibaud, with a glorious array of dramatically potent portamentos, is out in front; the quartet is sufficiently prominently captured for proper enveloping warmth at the key climaxes; and while it would be nice to hear more of Cortot’s smartly defined, characterful accompanying figuration, he’s up in the mix when it counts, his own top moments including a sudden, almost jazzy rubato nonchalance when the finale demands un peu plus lent (2'02"). It’s a little scrappy in places, but in the face of such fervent musicianship, who cares?

Onwards, and Jascha Heifetz and Jesús María Sanromá are nicely just out in front of the mahogany-dark Musical Art Quartet in 1941. While these pulsing readings strike on paper for their short running times, it’s only the Sicilienne – lilting at such a lick that it’s danceable as a Viennese waltz – that feels a tad fast. It’s more that momentum is subtly, satisfyingly retained over calmer episodes; and less satisfyingly that their finale features a car crash of a nine-stave cut at 6'41" (really, brace yourselves). Still, there’s plenty to love about Heifetz applying his white-hot intensity to Chausson’s 50 shades of passion, Sanromá’s ability to whip up a storm, their combined instincts over exactly where they can flex the metre, and the quartet right with them marrying power and precision.

Hearing Double

The viola player with the Musical Art Quartet was Louis Kaufman, and in 1951 he returned to the Concert wearing his violinist soloist hat, partnered with Artur Balsam and Quatuor Pascal. Engineering-wise, Kaufman is the winner, with Balsam’s piano sadly cotton-wooled. That said, few Grave climaxes have ever been delivered with such clarity, force and intensity, Kaufman’s violin burning luminously over the top (6'52").

Then in 1955 it was the Pascal’s turn to get a second pop at the Chausson cherry, with Yehudi Menuhin and Louis Kentner in a contrast-rich reading with an immediate (albeit not always suave) recording that does justice to their faithfulness to Chausson’s markings – relaxing more into his calando moments but without losing the architecture – and the resultant lucidity. Concerto-esque Menuhin has the odd messy moment, but no matter when it’s all so luxuriously and lovingly lyrical, gorgeously peppered with his singer-like slides. Listen to 5'47" onwards in the Grave for some supremely tautly expressive handling of tempo.

Sitting between those two are Zino Francescatti, Robert Casadesus and the Guilet Quartet, and in this bright capturing it’s the crisp-contoured string performances that are the winners. It’s a shame not to hear more of Casadesus’s light-and-shade virtuosity on his warmly songful instrument. Yet febrile-vibrato’d, string-biting, slightly nasal-toned Francescatti is master of the thrilling downwards portamento whoosh, and a sweetly husky dream at the close of the first two movements. This team pull right back in some of the calmer episodes, but the overall modus operandi is excited forward momentum (their airily delineated Sicilienne is another swift-ish one), including a crackingly energetic and nimbly passionate finale.

Sixties Opposites

While Lev Oborin explodes in as if for a Tchaikovsky piano concerto in his 1960 live account with David Oistrakh and the Borodin Quartet, he thereafter sounds as though he’s playing from behind a wall. There’s some impassioned playing from everyone here, despite some moments of imperfect ensemble. At times it drags, and at full volume it can sound heavy-handed (there are some very strange accents in the Sicilienne at 3'42"), but these musicians do melancholy and black despair achingly well, and the strings’ warm tonal quality is very fine.

Hard to pick any holes, though, with Christian Ferras, Pierre Barbizet and Quatuor Parrenin in 1968. This is exhilarating playing, captured in as high definition as the musicians’ clean-contoured, lucid-textured realisation of all Chausson’s dynamics and articulation. Red-bloodedly lyrical Ferras and low-on-pedal, jewel-toned Barbizet are perfectly spotlit, the fierily excited quartet tucked in snugly just behind. Relationships are correspondingly close. Barbizet grabs the music by its horns, sparkling with a panoply of nuance to his phrasing and shading, and exuding virtuosity. It’s strange that Ferras – light on portamentos but making them count – ignores some first-movement octaves (3'20"), but he otherwise plays the multicoloured virtuoso. Architecture is unwaveringly taut, and climaxes exhilaratingly supercharged. Fabulous.

Swings and Roundabouts

A generous room acoustic and full-blooded sweeping silkiness are the immediate impressions with former Vienna Philharmonic concertmaster Ricardo Odnoposoff in 1971 with Eduard Mrazek and the Austrian String Quartet. Piano is not Odnoposoff’s forte across this performance. Forte is, which can become exhausting. Yet the way each of his notes melts into the next is sublime, and he’s also a true chamber musician, happy to merge into the quartet texture when the score suggests. Mrazek meanwhile has a beautifully full, mellow, golden tone and a lovely freedom where freedom is appropriate.

There’s a lot of passion from Lorin Maazel in 1980, swapping his baton for his violin alongside his wife Israela Margalit and the Cleveland Orchestra String Quartet, but with balance, faithfulness to the score and finesse of technique and articulation, a bit of a mixed feast. The Sicilienne opening is rhythmically all over the place. Margalit’s rubato isn’t always sensitive to the ensemble effect. So notwithstanding the sheer showmanship of their finale, they leave the Eighties field wild open for Itzhak Perlman and Jorge Bolet with their perfectly weighted, eloquently lyrical, sensitively expressive and faithful-to-the-score recording with the Juilliard Quartet. Wrapped in a superbly tightly responsive team dynamic, this offers a momentum-filled first movement in which they relax but don’t sink into its pulled-back moments; a Sicilienne that’s perhaps a little swift, but also like musical dappled sun in its Gallic lightness, lucidity and lilt, growing to a rapturous climax; a beautifully coloured, deftly shaped Grave lament featuring a pulse-racingly fast-rising storm; then an assertive, gracefully springing finale.

The same year brings the ad hoc constellation of violinist Régis Pasquier and pianist Jean‑Claude Pennetier collaborating with Roland Daugareil, Geneviève Simonot, Bruno Pasquier and Roland Pidoux. It’s an invigoratingly more intense, weightily powerful take than Perlman et al, but they don’t come quite together as a unit. Tempo- and metre-wise, the Sicilienne goes uncomfortably in the direction of a slow movement and there’s rubato stickiness in the Grave.

Another beautifully rendered 1980s reading, from Augustin Dumay, Jean‑Philippe Collard and Quatuor Muir, appears to be no longer in distribution, beyond its Sicilienne on streaming platforms – a dream of warmly sepia-toned, sympathetically balanced, lucid-textured poetry that hits Chausson’s Pas vite direction parfaitement. Erato, bring it back!

Pianists on Top

Joshua Bell sounds soaringly, sweetly assertive on his take with Jean‑Yves Thibaudet and the Takács Quartet but slightly second fiddle in the balance to a more fuzzily captured Thibaudet, which is strange, but comes with the novelty factor of landing (attractively) piano details in our ears that we’re unused to hearing. The Takács is also quite far back, which is a shame when it’s so virtuosically all-in, top moments including, in the finale, its high-spirited rising chase with Bell at 6'35".

Pascal Rogé is equally kingpin pianist in 1994 with Pierre Amoyal and the Quatuor Ysaÿe – or at least Amoyal can sound quite thin and sharp against the piano’s slightly fluffier-edged, orchestral-width boom. There are some lovely moments, not least Amoyal’s touching nano-hesitations between his final Sicilienne rising semiquaver pairs. But while tempos and architecture are mostly satisfying (time-standing-still moments do occasionally get stuck), and there’s emotion, it feels like a slightly soupy clash of timbres.

Philippe Graffin’s violin is out to seduce in 1997 with Pascal Devoyon and the Chilingirian Quartet, launching into his first statement with rakish, bridge-rattling, portamento’d huskiness before morphing towards smoother debonair sweetness. The ensuing radiant reading doesn’t always have Graffin quite high enough in the balance and the Grave is a tad fast, but it does serve up a particularly beguiling blend of magically delicately voiced, woody-timbred Debussian freedom and lightness (listen from 4'00" in the finale), and proud Wagnerian ecstasy, Devoyon highly eloquent, and every note of the Chilingirian’s inner voices audible.

Stephen Shipps, Eric Larsen and the Wihan Quartet are good on rapture and warmth but there are issues with balance (notably Larsen’s piano sounding a bit behind and lost in the resonant space), messily meted rubato and some clunky technique. Vladimir Spivakov and Hélène Mercier with the Soloists of Moscow Virtuosi – Arkadi Fouter, Alexei Lundine, Igor Souliga and Mikhail Milman – are more polished, even if not always flowingly phrased. Truly quiet dynamics are rare on this weightily Romantic reading, and their pronounced relaxations of tempo and rubato touches mean things can drag.

A more satisfying warm, wide and luxurious take arrives in 2007 from silkily powerful former La Monnaie Opera Orchestra concertmaster Jerrold Rubenstein with Dalia Ouziel and a deferential Sharon Quartet in a generous room acoustic. Climaxes are big, heady and assertive. Rubenstein’s first-movement close is sublimely tender, as is the way the quartet meltingly stroke their accompanying chords to Ouziel in a languorous Sicilienne (0'51"). It’s a lyrical Grave lament, and while it’s a relatively stately, legato finale rather than a sharply articulated canter, it’s not without intensity.

Keep the lyrical poetry but with lighter-weight, energetically buoyant airiness and crisp definition, and you’ve got Soovin Kim, Jeremy Denk and the Jupiter Quartet in a forwards-pushing reading whose wide tempo variations are handled with organic-feeling flexibility and flow, every note audible. It’s an almost-swift, elegantly sunnily radiant Sicilienne, fluidly flowing even with all the air between its notes, Denk’s piano figures suggesting playfully rolling waves. Then a dry-textured, clean-contoured Grave – sober, tender but not despairing – and a nimbly, puckishly zipping-along finale with yet more deftly managed ebb and flow. Some will prefer more weight at climaxes but these don’t lack intensity or heart.

At the opposite end of the interpretation spectrum, the same year brings Dmitry Sitkovetsky’s string-orchestra ‘Concerto’ transcription, Sitkovetsky as violin soloist with Bella Davidovich and the Moscow Chamber Orchestra. Sitkovetsky has judiciously retained one-to-a-part where the writing begs, and it’s a poetic, darkly burnished and polished orchestral sound. Yet inner voices have become a background soup, it’s a narrow dynamic and dramatic range, and the outer movements feel as weighty as their long running times suggest (listen to the heavy work made of the first-movement excitement from 12'55").

It’s proudly expansive, orchestra-like expressivity from violin and pianist brothers Alain and David Lefèvre with Quatuor Alcan, over a nicely balanced take in a natural-sounding, not-too-close-miked acoustic. Interesting individual touches including the highlighting of the cello and viola’s rising and falling figures at the outset of the Sicilienne. Tempos, though, switch between satisfying flow and slowings that almost stop, and they apply the brakes in some strange places in the finale, such as right where Chausson asks for a return to his très animé tempo (8'00").

Jennifer Pike, Tom Poster and the Doric Quartet’s brightly captured 2012 reading also opts for a time-standing-still approach to the softer mid-movement interludes, but theirs is tautly handled, lightly worn flexibility, counterbalanced with exciting rhythmic forward thrust, the whole wrapped up in smartly met dynamics and all manner of tones and timbres. Their gentle Sicilienne is a beautiful palette-cleanser, filled with sensitive dialogue. The Grave packs a punch from whisper to tumult to the tense final climbdown as Poster slowly circles over the quartet’s luminous wide, reedy organ pedal; then an exhilaratingly, exuberantly charging finale couched in flexibly flowing, superglued rhythmic panache.

Lusty enveloping warmth, passion, soaring power and teamwork are what we get from Rachel Kolly d’Alba and Christian Chamorel with Spektral Quartet Chicago. Also a striking combination of tones, Kolly d’Alba’s husky-to-gravelly, highly vibrato’d ardent power (little upwards scoops into notes reminiscent of old-world playing) foiled by Chamorel’s brighter clarity and a darkly meaty quartet sound. Tempo shifts are marked but organic, retaining the architecture. Lower-volume dynamics sometimes get lost in the enthusiasm and Kolly d’Alba arguably blows her powder early in the run-up to the Grave’s true climax, but the Sicilienne balances delicacy and ardour perfectly.

The Concert hasn’t been much touched by period players, but the gut strings and 1885 Érard of the well-oiled team of Isabelle Faust and Alexander Melikov with the Salagon Quartet is a peach. Surprisingly orchestral-feeling, markings met to the letter, this lithely poetic, architecturally taut reading is more in the subtle Thibaud-Cortot school of tempo relationships, Faust offering a timbral and tonal palette from dark chocolate velvet to floating silver thread, as the quartet’s lack of vibrato yields multiple variations on glassy, lucid luminosity. While rhythms are smart and contours crisp, it’s not a bitey reading, but its charms are glorious; savour in the first movement the way the combined strings stroke then melt into their cumulative chord at 10'44". Savour too how, earlier at 9'00", the room’s bloom acts as a seventh instrument, Faust gliding through what sounds like perfumed piano clouds (8'55").

With Daniel Rowland and Natacha Kudritskaya we’re back to hand-picked friends over a permanent quartet – Francesco Sica, Asia Jiménez Antón de Vez, Joel Waterman, Maja Bogdanovic´ – and for all its panache-filled, concerto-esque feel, their fruitily Romantic reading (again making the room the seventh ingredient) has headily vibrato’d Rowland balanced so as to suggest a strings partnership of near-equals – further accentuated as the quartet’s various solos begin to pop characterfully out. Rowland arguably dips down a bit low at points, and it’s not always neat. But its passion and its sense of contrasting but complimentary personalities coming joyously together to converse are delicious.

In 2019 Daniel Hope followed in Sitkovetsky’s footsteps, playing as violin soloist alongside Lise de la Salle in his own new string-orchestra arrangement performed by the Zurich Chamber Orchestra. Overall running times make it more within Chausson’s ball park than Sitkovetsky’s, excepting an exceptionally long-drawn Grave. Yet while you couldn’t hope for more elegantly gliding playing, and despite some first-movement fire from Hope, it’s largely the same soft, serene grace from end to end, with chamber intimacy and inner colours gone. Add some luxuriously expansive moments that arguably over-stretch things and momentum can sag. The finale feels much longer than it is.

No such momentum issues with Quatuor Ébène violinist Gabriel Le Magadure, Frank Braley and the young Quatuor Agate. Faithful to the score’s tempo, dynamics and articulation, this finesse-filled, drama-rich account represents a high-definition feast of colour and timbre, its waxing and waning happening with taut organicism. Le Magadure delivers rich, proud, clean-lined nobility to Braley’s virtuosity, sensitivity and lyricism, while the quartet ardently accompany, comment and embrace. Weighting between parts feels spot on. It’s a rapturously warm, wide, sweetly radiant Sicilienne climax, a gripping Grave and a finale brimming with buoyancy and bite.

Running times-wise, you couldn’t put a candle between theirs and those of Daishin Kashimoto, Éric Le Sage and the Schumann Quartet, handling the sectional writing similarly, and equally sensitively attuned to each other and to the score’s detail. It’s perhaps a slightly lighter tone colour; Kashimoto’s portamento perhaps more violinistic, Le Magadure’s more singer-like; the Schumann perhaps suaver than the Agate, their ear-pricking individualities including spacious legato handling of the first movement ppp quaver triplets (10'30"), and highlighting the D flat in the penultimate Grave pedal; followed by a flowing, urgent finale.

Then, like buses, along come French chamber collective I Giardini with another strong 2024 offering featuring Pierre Fouchenneret as solo violinist, the recording just far back enough to make balance more about placement than weight. Warmly full and poetic, these readings balance ardent, spacious dreaminess with vibrant momentum, their romantically legato approach to the finale lending a lovely whimsical dreaminess at points.

In the context of the final two recordings appearing even as I put the finishing touches to this Collection (the Le Magadure set was a 2024 release, despite its 2022 recording date), and of the Concert popping up increasingly often on concert programmes, one wonders how many further offerings might appear over the course of 2025. Clearly it’s having a moment; perhaps this is also why the standard of recordings is increasingly high – and note that all but one of my final choices are comparatively recent releases. Know too that the decision-making was unusually difficult. All the choices could reasonably have taken the top spot, so I’d urge you to listen to all four before making your own decision.

TOP CHOICE

Le Magadure, Braley; Quatuor Agate

Appassionato, Le Label

Song, flight and bite, delivering proud, sensuous largesse, passion and thrill without going bull-in-the-china-shop or losing lucidity or rhythmic crispness. It’s a perfect blend of chamber work and concerto, and you believe every note.

THE ALTERNATIVE

Pike, Poster; Doric Qt

Chandos

Frankly, it’s almost impossible to call between this joyously close-knit team and that of Le Magadure. Slightly lighter-toned overall, they take their calando drops down further, with quieter, dreamier results, and their finale is a cracker.

CLASSIC CHOICE

Perlman, Bolet; Juilliard Qt

RCA

Narrowly pipping Ferras and chums to the post on account of its more polished capturing, this recording set a standard for faithfulness to the score, architecture, chamber dynamic and heart-filled playing that still today is more met and differed with than exceeded.

GUT INSTINCT

Faust, Melnikov; Salagon Qt

Harmonia Mundi

There’s no doubt that the combination of gut strings and Melnikov’s gorgeous Érard have a beauty all of their own, but really it’s the nuanced poetry of the playing, with a much richer-toned string sound than you’d imagine, that makes the magic.