Beethoven's ‘Waldstein’ Sonata: a guide to the greatest recordings

Patrick Rucker

Friday, February 15, 2019

Beethoven’s Op 53 represented a revolution in his piano style, says Patrick Rucker, as he sifts through almost a century of recordings

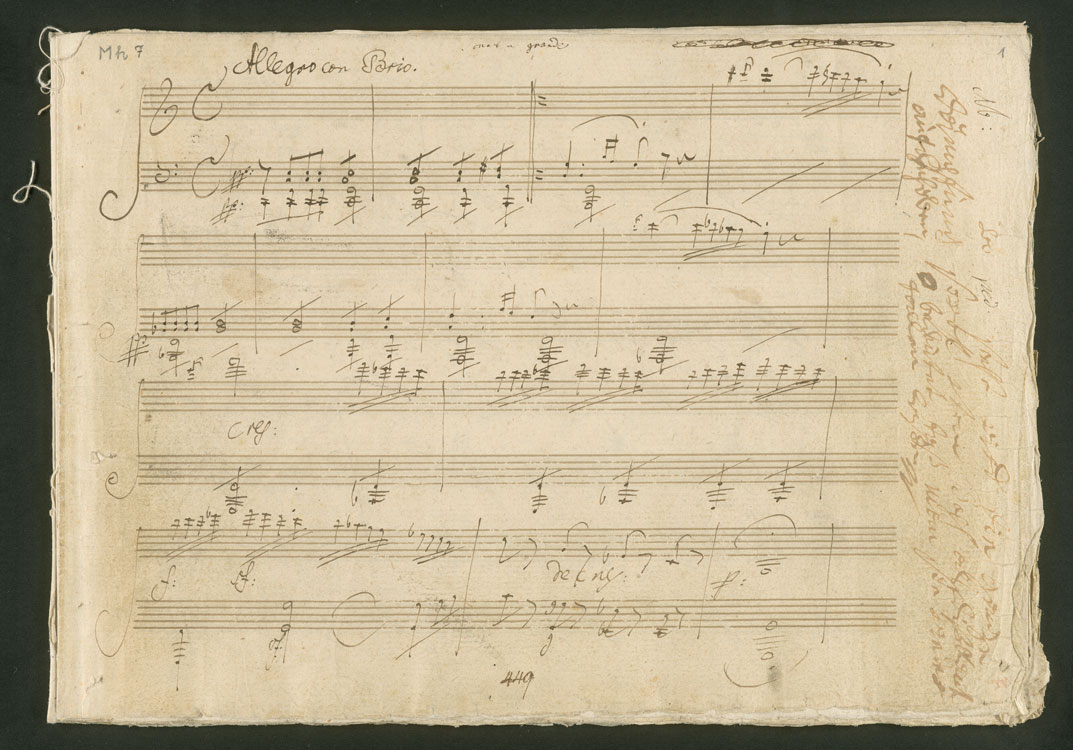

Beethoven took greater care of his sketchbooks than he did of his finished manuscripts. One of those fabled laboratories of creative imagination is called Landsberg 6, named for a collector who purchased the carefully bound volume after the composer’s death. Beethoven used it from late 1802 through early 1804, covering its 192 pages with several hundred sketches and drafts, including early ideas for both the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, as well as for the Triple Concerto and Fidelio. But the most extensive sketches are those for two large-scale works, each of which would be a pivotal landmark in its genre: the Eroica Symphony and the Waldstein Sonata.

The Sonata in C major, Op 53, was published in Vienna in May 1805 with a dedication to Beethoven’s early friend and patron Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel, Count von Waldstein (1762-1823). Born in Vienna, Waldstein lived in Bonn from early 1788, where he was made a knight of the Teutonic Order and became a privy councillor to the Archbishop-Elector. One contemporary report mentions that the young composer ‘often received financial support’ from Waldstein, ‘bestowed with such consideration for his easily wounded feelings that Beethoven usually assumed they were small gratuities from the Elector’. It was the Count who, in November 1792, wrote in Beethoven’s album the oft-quoted prediction: ‘With the help of unceasing diligence you will receive the spirit of Mozart from the hands of Haydn.’ Although the two men had long been out of contact, Beethoven’s dedication of Op 53 was the richest possible fulfilment of his friend’s prophecy.

The most obvious feature distinguishing the Waldstein from the 20 sonatas Beethoven had already published is its extraordinary technical challenge, well beyond the ken of any amateur pianist of the day. A review in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung concludes: ‘The first and last movements belong among the most brilliant and original pieces for which we are grateful to this master, but they are also full of strange whims and very difficult to perform.’ Unlike any other sonata, all three movements of Op 53 begin pianissimo. An extraordinary sense of propulsion is established at the outset of the opening Allegro con brio, also without parallel in Beethoven. Moreover, as Charles Rosen pointed out, many harmonic, figurative and textural procedures that had formerly been reserved for concertos are introduced into the framework of a sonata for the first time, lending the Waldstein its special drama and brilliance. The sonata’s expanded keyboard compass, along with its unconventional pedal indications, was clearly inspired by the fine Érard piano that the Paris maker sent Beethoven in 1803.

Beethoven himself never played his sonatas publicly, though it seems his pupils Carl Czerny, Dorothea von Ertmann and Ferdinand Ries did. Ignaz Moscheles too was an important early Beethoven exponent but it was the later generation of Franz Liszt and Clara Schumann who fixed the sonatas at the core of every pianist’s repertoire. Two pupils of Czerny who would become prolific teachers themselves, Liszt and Theodor Leschetizky, established the pianistic bloodlines leading back to Beethoven that, as demonstrated in this discography, are still traceable today.

As befits an innovative and visionary artwork that has been the object of widespread, admiring attention during the 214 years of its existence, some 175‑odd recorded performances crowd the current catalogue. A mere 20 have been considered here, unfortunately excluding many distinguished Beethovenians – Edwin Fischer, Rubinstein, Kempff, Arrau, Annie Fischer, Kovacevich, Pollini, Goode and Schiff among them. My choices were motivated by the diversity of approach the Waldstein has inspired, the chance to advocate for lesser-known recordings and, of course, personal preference.

Echoes of the 19th century

Of the last generation of Liszt pupils, the Scots pianist Frederic Lamond was internationally acclaimed as a pre‑eminent Beethoven player. One of his favourite recital programmes began with the Hammerklavier, followed by Opp 110 and 111 and the Waldstein, and concluded with the Appassionata. Ward Marston’s superb transfers of the 1922‑23 Waldstein Lamond made for HMV give a good idea of what a formidable Beethoven interpreter he must have been. Lamond’s playing has an inerrant sense of momentum and a high degree of accuracy, and is filled with vivid contrasts. Interestingly, Lamond doesn’t observe the slight caesuras between texturally contrasting sections that most players do today, as for instance in preparing the chorale-like second theme of the first movement. There is also a tendency, typical of the period, to short-change rests. What does emerge is a structural grasp that lends the sonata a compelling expressive arc, without stinting on detail. The sprightly, brilliant and beautifully paced Prestissimo coda of the last movement is a sheer delight. Above all, Lamond’s enveloping love of the music seems to permeate every bar.

More than any other pianist, Artur Schnabel is virtually synonymous with Beethoven. He first played the series of 32 sonatas at the Berlin Volksbühne in 1927, repeating the cycle in Berlin again, London and New York. Despite his ambivalence towards the studio, Schnabel’s complete Beethoven sonata cycle for HMV, set down between 1932 and 1935, was the first to be recorded. The continued prestige of Schnabel’s recordings, however, is not due solely to precedent but to their enduring musical qualities. In many ways, his Waldstein is typical of his way with the middle-period sonatas: extremely rapid outer movements, sometimes hectically rushed, and an extraordinarily slow middle movement that collectively result in a cohesive and intellectually compelling performance of singular power. Another Schnabel trademark, figuration played with great expressivity, is also prominent throughout.

On April 18, 1969, four months prior to his death at 85, Wilhelm Backhaus was recorded in a recital at the Berlin Philharmonie consisting of four Beethoven sonatas: Opp 28, 31 No 3, 53 and 109. One of the strongest techniques in modern piano-playing was still relatively intact. Even more remarkable is that Backhaus’s musical sensibility, essentially formed before the turn of the 20th century, sounded so freshly robust. Here, after all, was a pianist who studied with d’Albert and had been discovered by Nikisch. Naturally, Backhaus’s Waldstein contains discernible hints of his advanced age and musical vintage. More than a few octaves are split, for example, chords in both hands are slightly arpeggiated on occasion and the Prestissimo coda is slowed down to accommodate octave glissandos played from the wrist. Nevertheless, Backhaus’s straightforward, heroic concept, imaginative exploitation of instrumental sonority and proliferation of finely executed details mark his Waldstein as fully representative of the 19th-century ‘grand manner’.

Walter Gieseking, on the other hand, came of age during the 20th century, and his Waldstein, recorded in 1951, exhibits some aspects recognisable as 19th-century holdovers and others as more modern. The Allegro con brio, played without repeat, is one of the more relaxed of the recordings examined here. There is little of the flawless legato and intellectual rigour of Schnabel or the robustness of Backhaus. The Adagio molto of the middle movement is sped up to an andante comodo, mitigating its contrast with the outer movements. Ultimately, Gieseking’s fastidious Waldstein sounds more dutiful than inspired. In his defence, Harold Schonberg observed that listening to Gieseking after the Second World War was almost like hearing a different pianist.

Emerging voices after the Great War and beyond

Within eight days in 1903, two pianists who became noted Beethoven exponents were born in the Habsburg Empire: Rudolf Serkin (born March 28 in Eger, now Cheb, Czech Republic) and Lili Kraus (April 3 in Budapest). In concert, Rudolf Serkin projected a disarmingly human persona. One felt in the presence of a formidable musician, deeply reflective, always modest and self-effacing, who shared with his listeners both the loftiness of his goal and, however unwittingly, the herculean effort its achievement cost him. Something of this self-imposed pressure, as well as his innate personal sweetness, carries over into Serkin’s 1952 recording (he re‑recorded the Waldstein in 1975 and in a still unreleased 1987 session). Serkin’s extrovert reading, with its pervasive non-legato in the opening Allegro, some heavy lifting in the Rondo and overall steely sound renders this a monument to Beethoven in handsome, rusticated stone.

During the 1920s Lili Kraus often made her debut with various European orchestras playing Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto. However, it was her widely admired recordings of the violin sonatas with Szymon Goldberg the following decade that secured her reputation as a Beethoven interpreter. In her 1953 Waldstein, the opening repeated quavers create an uncanny sound, evoking lower strings using the smallest bow strokes, as though a continuously sounding triad were pulsating. Throughout the movement, the dynamic elements of the sonata-allegro dialectic are vividly characterised. The Introduzione describes a new landscape, self-contained and rhetorically poised. When profound introspection yields at last to open vistas, the music embarks on a lofty trajectory that lasts until the Prestissimo coda, which erupts in a celebration so ebullient that its earthy roots cannot be denied.

However complicated the artistic legacy of Emil Gilels may have become in light of post-Soviet historiography, the high standards of his pianism remain inviolable. Most pianists would prefer tackling the Waldstein after warming up to the hall and audience but Gilels was so comfortable with the piece that he didn’t hesitate to programme it first in his recitals. His 1972 recording for DG was intended as part of a complete set of Beethoven sonatas left unfinished at his death. Gilels’s preference for the Apollonian over the Dionysian produces an opening movement with an unhurried Allegro minus the con brio. The Adagio remains imperturbable throughout, resulting in a Rondo that, despite all its sonorous beauty and indisputable decorum, is slightly anticlimactic. If one is left wanting a greater degree of personal involvement, Gilels’s finely calibrated technical polish can still inspire awe, even in our age of technically flawless pianism.

Listeners with no first-hand experience of the iconoclastic, fiercely contrarian pianist Friedrich Gulda who, from the 1950s, actively pursued interests in jazz and composition alongside his career as a classical pianist, may be surprised to hear in his Waldstein scant evidence of the improvisational freedom or personal utterance his extra-classical interests might suggest. Temperamentally, Gulda’s interpretations tended towards the objective. If less strait-laced than his Bach performances, this taut and stringent Waldstein from 1957 seems little concerned with variety of touch or colour. Gulda’s liberation from what he came to consider the hidebound rigidity of his classical training was yet to come.

As befits a career in which Beethoven has occupied prime real estate, the Waldstein of Alfred Brendel commands great authority. Had Brendel not written perceptively about many aspects of Op 53, it would be obvious from his performance alone that his final conception emerged only after all possible interpretative implications were scrutinised and weighed. Brendel’s Waldstein contains extraordinary richness in both colour and detail that yearns towards Romanticism, yet remains within Classical realms in its objectivity and proportion. His ability to vividly convey Beethoven’s mighty architecture, to disambiguate points of departure and arrival, is one of Brendel’s many strengths. His seriousness of purpose is echoed in the Philips engineers’ wonderfully lifelike sound in this 1993 recording, allowing us to hear not only the piano but the room as well.

When Daniel Barenboim first played the 32 Beethoven sonatas in Tel Aviv in 1960, he was the youngest pianist in recent memory to play the entire cycle publicly. Certainly few recording artists may claim a closer first-hand relationship with Beethoven, since Barenboim’s experience as both conductor and pianist includes the symphonies, concertante works and choral and chamber music, in addition to solo piano works. The Waldstein considered here was filmed live during eight concerts at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden, Berlin, in June and July 2005. First released as an EMI DVD set, it has subsequently been released as CDs on Decca. In clarity and precision, with every element scrupulously ordered, Barenboim’s Waldstein is probably sui generis. His perfectly gauged, pure sound is a marvel and could serve as a metaphor for Barenboim’s intellectually honest playing. Yet the flipside of this Olympian conception is a certain sense of removal from emotional immediacy. The performance of this particular sonata seems curiously free of spiritual struggle, without which an urgent sense of resolution remains remote.

The later 20th and early 21st centuries

It is more than three decades since Jenő Jandó recorded Op 53 as part of his complete series for Naxos, turning in a performance that has proudly withstood the test of time. When Jandó’s Beethoven is mentioned among recommendations for complete sets, as it almost invariably is, the discussion always seems prefaced by ‘for the budget-conscious’. Certainly this Waldstein needs no such qualification. In a vibrant and sparklingly clear Allegro con brio, phrases are given plenty of room to breathe, even as Jandó maintains a propulsion that brooks no impediment. This is no engine firing on all cylinders but an implacable forward surge, fuelled by boundless exuberance. But there’s more here than visceral excitement. Once the development really gets cooking, conscientious artists will sometimes over-characterise the thematic hide-and-seek, creating an inadvertently comic effect. Jandó takes another path. He creates a steady build almost from the beginning of the development, incrementally increasing in tension and mass until we feel perched at the summit of a towering mountain range. Then, with a sudden turn of the wheel, we’re back in the open terrain of the recapitulation, in a display of exhilarating mastery that seems a force of nature.

When the definitive cultural history of music-making after the Second World War is written, surely the so-called Historically Informed Performance movement will loom large. For pianists, its influence has spread beyond practitioners of early instruments and enriched mainstream pianism. According to Ann P Basart’s discography The Sound of the Fortepiano, Jörg Demus made the first recording of the Waldstein on a historical instrument in 1970, using an 1802 Broadwood. It was over a decade before the next recordings appeared, by Paul Badura-Skoda, Malcolm Binns and Anthony Newman, all in 1981.

The first of the two ‘original instrument’ recordings in this discography, however, is the 2007 recording of Ronald Brautigam. His Waldstein uses a Paul McNulty replica of a Conrad Graf instrument from about 1819 and is part of a series of Beethoven’s complete piano music on BIS. Listening to Brautigam, we hear the special qualities of clarity and definition, the pure colour palette, the differentiation of registers and the altered proportions inherent in early 19th-century pianos. But we also hear ardent, witty, perceptive music-making of breathtaking virtuosity and charm.

Louis Lortie, on the other hand, seems intent on mining every last expressive nuance the modern piano is capable of in his 1991 Waldstein. The shapely phrasing and flowing contours make this a sensually beautiful reading. Not surprisingly for a pianist who excels in many varied repertories, Lortie seems fully present in every bar. The same might be said of Andreas Haefliger, each annual instalment of whose ‘Perspectives’ series, begun in 2004, is built around a Beethoven sonata or two. He plays a heartfelt and stylish Waldstein that is rhetorically apt and rich with imagery. Surely few pianists are more dedicated to Beethoven than Haefliger, and his programming is a strong argument for recording the sonatas over an extended period rather than during the two- or three-year total immersion that many pianists have required to record all 32. François‑Frédéric Guy set himself the extraordinary challenge of recording his sonata cycle live in 2010 in Ricardo Bofill’s exquisite, repurposed room of the Arsenal in Metz. The outer movements of his Op 53 are not overly fast but appropriately energetic. The Adagio molto, on the other hand, is very slow indeed and provides not only contrast but the platform from which the Rondo takes wing, with plenty of reserves left over for the Prestissimo coda.

The Waldstein of Steven Osborne is at once original in concept and the attainment of a classical ideal. In an Allegro con brio fairly bursting with energy and rhythmical élan, the overriding impression is one of profound lyricism. Beautifully shaped phrases are set in textures of sumptuous variety. Osborne has an amply equipped arsenal of attack-and-release strategies throughout his range but his infinitely calibrated dynamics are most remarkable at the soft end of the spectrum. The intricate drama of the development unfolds with an urgency that keeps you on the edge of your seat, uncertain of the outcome. Any shift from this heightened level of excitement might seem abrupt but the Adagio immediately establishes the aura of hallowed realms, imbued with oracular mystery. From there, an atmosphere of ethereal calm attends the first glimpse of the Elysian Fields at the beginning of the Allegretto moderato. The remaining peaks and valleys are navigated without misstep and always with an eye towards grandeur.

Steeped as he is in the idioms of Beethoven and Schubert, Paul Lewis plays an Op 53 that can afford to part company with the mainstream. Eschewing extroversion, the opening Allegro seems almost quietly confiding. In fact, an aura of intimacy envelopes the entire sonata, appealingly and quite persuasively, thanks to the earnestness and strength of Lewis’s musical personality.

Listening to Jonathan Biss’s 2013 Waldstein, one intuits a musical sensibility whose prime motivating purpose is the understanding and imaginative re‑creation of Beethoven. This sensibility is fortified by deeply cultured musicianship, enriched with an aural imagination satisfied only with the fullest exploitation of the piano’s expressive sonorities. In combination, these attributes result in a grippingly persuasive Waldstein. The Allegro con brio proceeds as if an epidemic of energetic joy were run rampant. The voice speaking at the outset of the Adagio is so self-effacingly reverent that when it rises in eloquent song, it comes as a surprise. Certainly flight informs the finale, but so do the roar of cataracts, the progress of mighty rivers, great winds and abundant sunshine. At the Prestissimo coda, it’s as though every bell in Vienna has begun to ring at precisely the same moment. This is a Waldstein that fulfils Cicero’s rhetorical imperative to inform, persuade and delight, though Biss provides a triple measure of the latter.

Extraordinary poise and polish characterise the 2015 Waldstein of Boris Giltburg. The same freshness of vision encountered in his superb Rachmaninov recordings is evident, as though the interpretation had been painstakingly built from the ground up, free of preconceptions or received wisdom. Transparent textures have the clarity of a mountain spring and Beethoven’s architecture is cast in a brilliant light. (More’s the pity he omits the repeat of the first-movement exposition.) There are moments, however, when Giltburg’s penchant for clarity puts him at odds with the washes of sound Beethoven clearly indicates with his lavish pedal markings. The Rondo seems somehow restrained, as if Giltburg were bridling his natural instincts. But it’s in this same Rondo that his extraordinary left hand, seemingly with a mind and will all of its own, is showcased.

The last of our Waldsteins is also, hands down, the most orchestral in sound. That is due in part to the excellent fingers and aural imagination of Olga Pashchenko but also to her instrument: a Viennese by Conrad Graf from 1824, held at the Beethovenhaus in Bonn, which dates from one of the more extravagant periods of piano manufacture and has, among other features, five pedals. The qualities of this piano, which can sound so exotic to us, were in fact typical of the instruments Beethoven knew and loved.

Conclusion

There are four recordings I value above the others, which means they’re the ones I listen to most frequently, always with pleasure. They have certain things in common. Each artist seems to me fully present in every note and has internalised Beethoven’s message, as each understood it, to the extent of making it completely his or her own. Recreating this unique masterpiece via the medium of recording, all seem to have done so with great conviction and from a full and open heart.

The earliest is that of Lili Kraus, whose conception strikes a balance between extroversion and inward eloquence, bringing to mind some of the finer aspects of European sensibilities before the Great War. I treasure Jeno˝ Jandó’s performance for its bracing emotional health and unaffected candour. Very few pianists before the public today equal Steven Osborne’s sovereign mastery of so many diverse repertories; Osborne’s Beethoven speaks with earnestness and moral authority, and his Waldstein Sonata, in terms of clarity, proportion and sheer beauty, exemplifies a lofty classical ideal. But if some cruel circumstance left me with the choice of only one recording of the Waldstein for the rest of my days, I would take the one by Jonathan Biss, for its wit and youthful optimism, its breadth and the humanity that informs its portrayal of Beethoven’s masterpiece.

The Historical Choice

Lili Kraus

Without exceeding classical restraint and proportion, Lili Kraus, in her 1953 recording of Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata, achieves a rhetorical eloquence that is simultaneously exalted, richly imaginative and deeply personal.

The Budget Choice

Jenő Jandó

From beginning to end, Jenő Jandó exudes a robust health and directness of utterance that guarantees this Waldstein – now over 30 years old and part of Jandó’s complete sonata cycle for Naxos – a place among the most satisfying.

The Spiritual Choice

Steven Osborne

Over the course of 27 riveting minutes, Steven Osborne creates a trenchant musical narrative spanning three disparate movements, suggesting a compelling spiritual journey of transformative power.

The Ultimate Choice

Jonathan Biss

Jonathan Biss launched his highly regarded Beethoven sonata survey in 2012 and it continues with annual releases. There is something elemental in the way Biss evokes the titanic Beethoven but he does so with the most exquisite, unforced, multi-dimensional sound, rendering it profoundly human.

Selected Discography

Recording Date / Artists / Record company (review date)

1923 Frederic Lamond / Marston 52701-2 (4/25R)

1934 Artur Schnabel / EMI/Warner Classics 265064-2 (10/36R, 8/09); 9029 59750-5 (12/15)

1951 Walter Gieseking / EMI/Warner Classics 567585-2 (10/53R)

1952 Rudolf Serkin / Music & Arts CD1141

1953 Lili Kraus / Erato (31 discs) 2564 62422-3 (1/15)

1957 Friedrich Gulda / Decca 443 012-2DF2

1969 Wilhelm BackhausAudite AUDITE23 420

1972 Emil Gilels / DG 419 162-2GH (11/72R, 8/86)

1987 Jenő Jandó / Naxos 8 550054

1991 Louis Lortie / Chandos CHAN9024 (4/92)

1993 Alfred Brendel / Philips 438 472-2PH (11/93)

2005 Daniel Barenboim / EMI 368996-9; Decca 478 3549DX10

2006 Paul Lewis / Harmonia Mundi HMX290 1902/11 (12/06R)

2007 Ronald Brautigam / BIS BIS-SACD1573

2008 Steven Osborne / Hyperion CDA67662 (6/10)

2008 Andreas Haefliger / Avie AVIE2173 (7/10)

2010 François-Frédéric Guy / Zig-Zag Territoires ZZT304 (A/12)

2013 Jonathan Biss / Onyx ONYX4115 (3/14)

2015 Boris Giltburg / Naxos 8 573400 (10/15)

2016 Olga Pashchenko / Alpha ALPHA365 (10/17)

This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about sucribing, please visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe