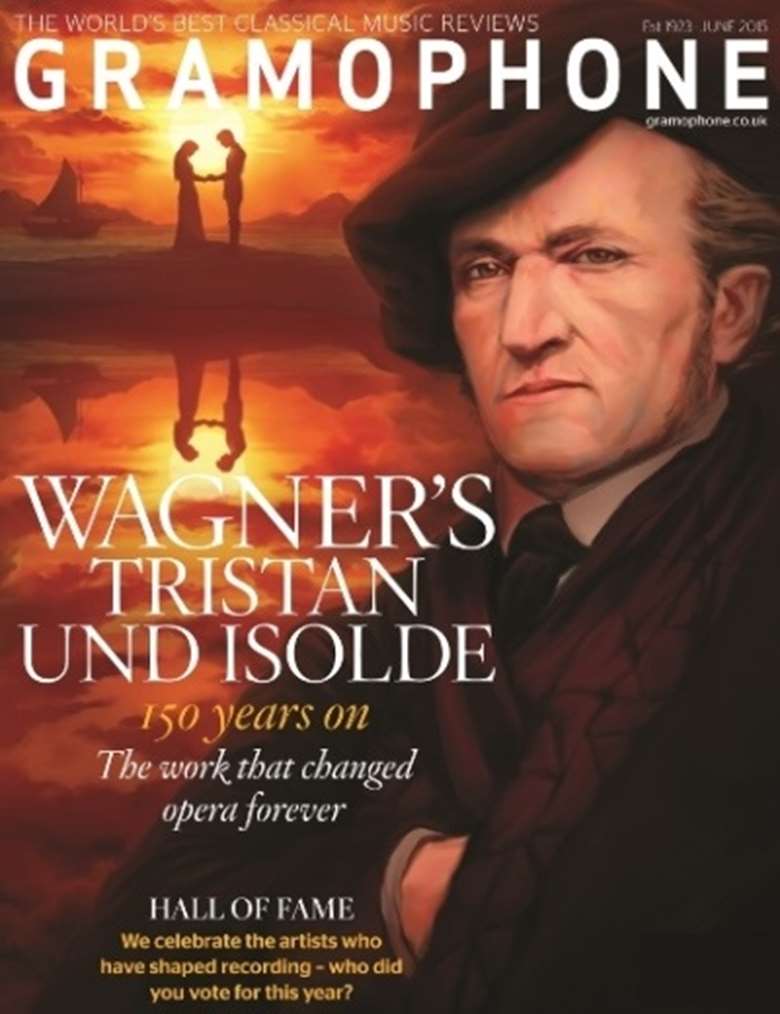

Wagner's Tristan und Isolde

Gramophone

Wednesday, January 21, 2015

A survey of recordings of Wagner's opera, which weaves a powerful spell over performers and audiences alike, by Alan Byth (Gramophone, October 1998)

Those yearning phrases that ignite the Prelude, once heard never forgotten, opened a new era in opera. I first encountered them, and the whole work, at Flagstad's farewell to the role of Isolde at Covent Garden in 1951, after which she moved her audience to tears with her few, simple words bidding her audience adieu. Soon afterwards the great HMV recording with Flagstad conducted by Furtwängler appeared, the first totally complete set of the work. The old red-and-gold sleeves and their magical contents were constant companions in the ensuing years. Then in 1969 I heard Nilsson and Windgassen at Bayreuth, in the unforgettable Wieland Wagner staging, three years after Böhm had recorded it. I came out into the balmy night reeling from the experience, an amazingly concentrated traversal of the work, as it still sounds. In 1975, also at Bayreuth, I was back to hear Carlos Kleiber's incandescent reading, another unmissable, very different performance committed to disc later in the studio.

These conductors, also Goodall and Barenboim, whom I later encountered in the opera house, reveal on disc different facets of a piece that will never have one, definitive reading. All draw you ineluctably into its strangely compelling, almost hypnotic world from which there is no release until those final, cleansing chords that follow the Liebestod. It is indeed impossible not be caught up in each and every exposition of the love-death theme so astoundingly proposed by Wagner, largely because the executants seem as spellbound by the work as the listener.

Lately archives have opened: authorized and unauthorized sets have been issued, extending appreciably our discography of Tristan. We can now hear Flagstad's Covent Garden debut in the role under Reiner in 1936 on VAT; the odd conflation of Beecham and Reiner 1936-7 on EMI; both having Melchior as Tristan, a 1940 Met broadcast with the same principals under Leinsdorf, a 1943. Berlin broadcast with Paula Buchner and Max Lorenz that I reviewed last month; the 1950 Munich revival under Knappertsbusch; and the 1952 Bayreuth performance, Wieland's first staging of the work, with Karajan, Martha Mödl and Ramon Vinay, a reading that has a deserved reputation among Wagner addicts. It is a formidable field.

Furtwängler

Wilhelm Furtwängler's remains the Ur-Tristan set, the one by which all others are still measured - and rightly so. To this day no more succinct summing-up of its virtues has been written than that in the old Record Guide (Collins: 1955) contemporaneous with its first appearance: the authors wrote that, under Furtwängler, the work "overwhelms the attentive listener anew with its tragic intensity, its musical logic, its pathos and its sheer sensuous beauty". Listening to it yet again for this survey, I can only underline that description, even if the digital remastering for CD has lost some of the warmth of the original. Inspired by their conductor, the Philharmonia, in their heyday, play the score as if their life depended on it. The results, both in detail and as a whole, are tremendous, seconding FurtwSngler's very free yet always flowing interpretation. As extracts from various stage performances issued since have shown, Furtwängler could be even more volatile and visceral in the theatre, but under Walter's Legge's watchful ear and eye, much of the operahouse excitement is caught in the studio.

Flagstad, no longer as youthful in voice as in the live, 1936 reading (see below under "Historic performances"), remains an Isolde of vocal refulgence who sings everything with warmth, musical understanding expressed in shapely phrasing and commanding power. As has been said she represents all womanhood rather than merely one, erotically minded heroine. She isn't as electrifying in her declamation as some in Act 1, but few if any sing Act 2 so lovingly. When first reviewing the 1936 set I mistakenly claimed that she was there almost as discerning as in 1952. Not so: this later performance is more thoroughly thought through, more keenly conceived. Twenty years' stage experience of the part wrought a change.

Suthaus is one of the most convincing of all Tristans, a portrayal illumined from within by a profound understanding of the role's needs and executed by one of the most expressive Heldentenors ever recorded. With Furtwängler in inspired support the Act 3 deliriums are shattering yet never taken beyond the bounds of musicality. The Vision, "Wie sie selig", thereafter is heartstopping in its intensity. Greindl shapes and enunciates Marke's Lament with almost as much insight and verbal imagination as any of his predecessors or successors. Fischer-Dieskau does as much for Kurwenal, but his voice is altogether too light for that grizzled warrior. Thebom is a nondescript though vocally pleasing enough Brangäne. No, greatness here lies in Isolde, Tristan, Furtangler and the orchestra. Listen to the opening scene of Act 2 as the noble conductor unfolds layer upon layer of pent-up emotion, and Isolde's Lament over her lover's body, also her Liebestod in Act 3, and you're unlikely to want to be without this classic.

Solti and Karajan

Nearly ten years later, in 1960, came Sir Georg Solti, so far his only attempt on the work on disc. I can do no better than quote David Hamilton's graphic description of this Decca version (Metropolitan Guide to Recorded Opera; Thames and Hudson: 1993), when he describes it as "alternating between punchy hot spots and static torpor", tallying with my more mundane description of the set, in June 1990, as veering between "being becalmed and frenzied". The voice of Nilsson in its absolute prime is a thing to wonder at, but by Bayreuth 1966 under Böhm the interpretation had grown immeasurably. I am willing to break a lance for the underrated Fritz Uhl, who gives an unfailingly musical account of Tristan's music, wanting only the ultimate in dramatic conviction. Tom Krause's virile, youthful Kurwenal is the best of a so-so supporting cast. John Culshaw's production brings the orchestra too far forward in relation to the the singers. Not one for the library.

Karajan's official (ie EMI) recording of 1971-2 is also inessential. It has always been controversial; indeed, so eminent a voice as John Steane has been known audibly to eat his words on a BBC Radio 3 survey of the opera, changing from praise to excoriation of the set. It has always seemed to me ponderous, calculated and studio-bound, a stodgy sound made worse by constant fiddling (by Karajan?) with the recording level: it is no match for his 1952 Bayreuth reading (see below, "Live from Bayreuth"). Dernesch, a lovely and moving Isolde when she sang the part a year or two earlier with Scottish Opera, has lost her freshness and ease of tone although she still pours it out evenly and unstintingly. Such is her concentration on that purpose that attention to the text often goes by the way. Vickers's ultra-anguished, overwhelming Tristan, sung in forceful but occasionally rasping tones, has always been an acquired taste, a searing portrayal that some consider the set's raison d'être. His frightening traversal of Tristan's Act 3 hallucinations, not for weak souls, is undoubtedly a gramophone classic, like it or not, of kind unlikely ever to be repeated.

Ludwig, as Brangane, sings generously but, like her mistress, with too little attention to verbal definition. Berry is a strong, honest Kurwenal, Ridderbusch a sympathetic but slightly cool Marke, sung with consistently smooth and beautiful legato, but the performance doesn't work as an entity.

Goodall

Sir Reginald Goodall's version is most notable, well, for Goodall himself, for his ability to allow us a convincing overview of the whole opera, based on an understanding of its melos and its structure. Both he and his personally instructed singers give us a gratifying stream of true legato based on the long phrase. They also favour old-style portamento, thereby forming a link with the wartime and early postwar performances. But there are downsides even to Goodall's contribution in an occasional tendency to lethargy where energy, or heady eroticism, might be preferable.

Neither the playing nor much of the singing is quite in a world class. Linda Esther Gray's unflinching, truly sung Isolde makes her early retirement seem all the sadder. Hers is a fully fledged assumption, benefiting from stage performances, often with the most impressive insights - try "Er sah mir in die Augen" (Act 1) - but her distortion of vowels is a distinct drawback, sometimes lending her tone a gluey sound. Neither Anne Wilkens's Brangäne nor Phillip Joll's Kurwenal is at all distinguished. Only Gwynne Howell, a warm, sensitive Marke, and John Mitchinson, as Tristan, have good German. Indeed, Mitchinson, often patronized in reviews of this set, now appears its chief asset, vocally speaking. His voice is adequate to all demands placed on it, he shows a true understanding of Wagner phraseology, above all, words mean something to him, and he conveys that to us. He isn't the most exciting Tristan on disc, but is certainly one of the most cogent.

Kleiber and Bernstein

The other version, with a British Isolde, Margaret Price, recorded coincidentally at about the same time as the Goodall, is a quite different proposition, indeed something of an antipole to Goodall's set. It enshrines Carlos Kieiher's incandsecent, quick-moving yet never superficial interpretation. This is a rare occasion when the frisson of a live reading has been caught to the full in the studio. "Spiritual fervour" and "burning fever" were descriptions of Kleiber's performances in the theatre during the 1970s that exactly equate to what we hear on disc. Extreme contrasts of speed and dynamics are part and parcel of this seemingly spontaneous account, yet they are intelligently integrated into the total picture. Similarly, it is perhaps the most intimate, the most poetic reading of all: when the lovers have drunk their potion, they come together not simply in an impassioned outburst, they also sound incredulous at their luck in finding each other. When Price's Isolde awaits her lover in the garden at the beginning of Act 2, she utters the phrase "Nicht ihres Zaubers Macht" with quite extraordinarily poetic wonder. Indeed, throughout, Price, Fassbaender and to a lesser extent Kollo, sing their roles with a Lieder-like attention to detail, perhaps possible only in the studio, as in Tristan's appeal to Isolde at the end of Act 2 and her reply. In any case it is wholly breathtaking - listen to Fassbaender's "Ich höre die Home Schali" at the start of the Act, and you'll hear what I mean. Yet theirs is an answering contrast and intensity in the climax of the love duet and in Tristan's second delirium that matches anything in the grander interpretations of, say, Furtwängler or Knappertsbusch. Everything is executed in dedicated fashion by the Staatskapelle Dresden, a great orchestra in great form - with violins split left and right, and winds prominent, among the most translucent on any version.

Price, as I have already implied, is an Isolde of innate musicality combined with pure, secure tone, the most subtle feeling for phrase and characterization the irony, frustration, the vulnerability too, of Act I finely expressed (listen to the accent on the single phrase "Den Helden"). Only the ultimate in heroic strength is wanting, and on disc one hardly misses it. Matching her in commitment, and in lyrical and verbal refinement, Kollo's Tristan joins his Isolde in a ravishing account of the love duet. The deliriums are searingly enacted, though, as with his Isolde, this Tristan doesn't have the classic voice nor the breadth of tone for the part.

Nor would you call Fassbaender's voice Wagnerian in the truest sense, yet she puts so much into the role, exhibits so much intelligence, that again absence of sheer decibels goes virtually unnoticed. Moll certainly is a Wagner bass. He brings his sterling voice and vast experience to bear on Marke's monologue, and is most affecting in the way in which he provides a palette of tonal colour and a range of dynamics to convey the king's pangs of betrayal.

Affecting too is the then 70-yearold Dermota as the Shepherd in Act 3. Fischer- Dieskau's Kurwenal, sadly declined in the 30 years that had elapsed since he previously recorded the role, blusters in ungainly fashion when under pressure but still has many proud, many touching moments in Act 3. Not everything is right in the balance between voices and orchestra (the latter sometimes too loud), but that doesn't detract from the great number of assets of this remarkable rendering.

Leonard Bernstein's 1981 Philips version, made at live concert performances of each act spaced out over several months with patching sessions, is predictably a thing of wide contrasts, often pushed to excess, and of visceral excitements. No other conductor risks so many extremes of tempo, few such a range of dynamics. When first listening one is carried away, as so often in a Bernstein reading, by the burning conviction of it all. When the head starts to temper the heart's reaction the exaggerations tend to pall. Perhaps this is a version to hear twice but not one for the library, but then one remembers all sorts of places where Bernstein, as a composer himself, 'reveals more of Wagner's creative process than any other, particularly where orchestral figures tell us what a character is really thinking or feeling. All in all this performance, in its spontaneity, is at the other extreme to Karajan's stiff discipline.

Few, if any Isoldes achieve the sheer piercing quality of Hildegard Behrens's emotional response to both words and music, or her sense of womanly vulnerability (listen to "Nun leb wohl Brangäne" in Act 1), but you have to be able to tolerate frequent unsteadiness and some ungainliness (in the lower register). She and the somewhat uncommunicative Tristan of Peter Hofmann, whose tone consistently lacks a true core, are often sorely pressed by Bernstein's slow speeds. While Minton as Brangäne, Weikl as Kurwenal and Sotin as Marke are all more than adequate, none has any special insights to bring to their roles. The recording gives too much prominence to the orchestra at the voices' (especially Behrens's) expense, and the changeovers on the newish four-CD transfers come at unfortunate places.

It was some 14 years until another version appeared, that conducted by Daniel Barenboim, which I discussed here last month. From the point of view of the conducting, this set, recorded in the full panoply of digital sound, is commensurate with the best of its predecessors, at least those made in the studio, Barenboim catching the surge and sweep of the work, attentive to its interior and exterior aspects and achieving superb playing from the Berlin Philharmonic.

Now I have had a chance to renew my acquaintance with all its rivals I find myself with even greater reservations about the new version's lovers. For all her understanding and musicality, Meier doesn't command the breadth of tone or depth of interior feeling of an ideal Isolde, and the sensitive Jerusalem often seems a trifle uninvolved as compared with his rivals. Lipovsek's undersung Brangäne is a liability, Salminen's searing Marke a notable asset. Struckmann's Kurwenal is more than adequate. This is a well-prepared, consistent version for anyone wanting a performance in the most up-to-date sound.

Live from Bayreuth

When we turn to live recordings, we enter another world, one in which the performances have, on the whole, a greater consistency of thought and execution. That applies in spades to the famous Bayreuth set of 1966 already referred to. Karl Böhm's swift, incandescent, very theatrical interpretation isn't to everyone's liking. Yet, for all the fast speeds, the charge of superficiality is misplaced. Böhm's direct, cogently thought through reading, in which tempo relationships, inner figures (as one might expect from a Mozart and Strauss specialist), and instrumental detail are all carefully exposed and related to each other, offers rich rewards. Expressive intensity is here married ideally to a transparency of texture. Above all, listen to the interplay between voice and orchestra, most notably in Isolde's Act 1 narration and Tristan's Act 3 deliriums. There are moments at the end of Act 1 and in the heat of the love duet when Böhm gets so carried away that his singers have almost to gabble, but they are a small price to pay for such immediacy of feeling.

As Isolde, Nilsson outsings all her rivals, Flagstad apart. The gleaming tone, the fearless attack (high As, Bs and even Cs come easily to this Isolde), the unflagging stamina of the performance are things to marvel at, but the interpretation is also astonishing, the anger, scorn and irony of Act 1, the sensuality of Act 2, the transfiguration of the Liebestod (begun with a lovely, soft-grained line) all unerringly achieved. Warmer Isoldes there may be; few are so proud and impassioned.

Windgassen's Tristan isn't vocally in his partner's class and starts in distinctly dry fashion, but the tenor understands the role like few others. His reply to Marke at the end of Act 2 is heartrending and he brings an inner conviction to Act 3, sung in plangent tones, that means so much more than extrovert gestures. Indeed, Act 3 is the suitable climax to the reading with the orchestra excelling itself, strings, wind and bass alike, all finely balanced by Böhm, and Nilsson in the context of a live performance -surpassing herself in emotion during Isolde's lament over Tristan's dead body.

Ludwig's Brangäne, so much more affecting here than for Karajan, is a perfect foil to Nilsson's Isolde, concerned, eloquent, using the text and line to portray all her variety of feelings. Talvela is a more youthful, virile Marke than some, which makes his collapse near the end of his long monologue the more moving. The enormous voice manages to project a profound melancholy. Waechter, forthright, big-boned, is among the best of Kurwenals, Schreier a prince among Sailors, Wohlfahrt a touching Shepherd. One notices again and again how Wieland Wagner (the producer) and Böhm between them get the German-speaking cast to enunciate throughout with meaning and clarity.

The recording, so much more natural than most of the studio versions, catches the special sound of the Bayreuth acoustics with a true balance between stage and pit. The performance is contained on three mid-price CDs, which adds further to this set's manifold attractions.

The other Bayreuth Tristan has never been issued officially (it has most recently been available on Arkadia CDs), but enjoys a high reputation, rightly so, among cognoscenti of the opera. The marmoreal Karajan of 1972 is replaced 20 years earlier by his pulsating, energetic, passionate alter ego, a youthful reading that benefits enormously from being caught live, the few dominoes soon forgotten in the truthfulness of the occasion - what a close to Act 1, what a love duet! The mezzo-ish Martha Mödl and baritonal Ramon Vinay, a richer voiced Tristan than Windgassen, were two of the most intelligent singing actors of their or any generation, and give intellectually and dramatically penetrating interpretations of the title-roles. Although both are vocally, and Vinay musically, fallible, they often reveal more of their characters' inner thoughts than any of their rivals. I recall Mödl in 1955 at the Royal Festival Hall in London with the Stuttgart Opera being a quite riveting Isolde: so she is here. Hotter's Kurwenal is overwhelming in his Act 3 compassion. Weber is one of the most heartfelt (so much colour in the tone and words) if not the most accurate of Markes. Ira Malaniuk, ordinary in Act 1, comes forth beautifully in Brangane's Watch in Act 2. Hermann Uhde as Melot – class casting - is striking in his malevolence, Gerhard Unger is a youthful Sailor, Gerhard Stolze a pointed Shepherd. The recording, in goodish mono, is worthy of this profound experience, something that simply could not be repeated with such conviction in a studio.

Historic performances

Hans Knappertsbusch at Munich in 1950 is even more engrossing - at least as far as he and his Isolde are concerned. The great conductor's impulsive reading, one concerned with narrative values and a total overview of the opera, is paradoxically at once a grand, metaphysical reading yet one that can offer the utmost refinement of detail. It is spontaneous, sometimes dangerously so, in the way tempos and markings are read, yet so convincing are the results that the spirit triumphs over the letter, nowhere more so than in Isolde's Narration. Surpassing even Mödl, Helena Braun here manages a kind of conversational, almost Sprechgesang style, making every word tell as would a Lieder singer. That makes her the most inward and very often the most eloquent of all Isoldes (apart perhaps from Buchner, see below) - listen to "Zu schweigen hat ich gelernt" in the Narration, at once ironic, sad, bittersweet, or, at the start of Act 2, to "Nicht ihres Zaubers Macht", or to all of her Act 3 Lament, so intense, impassioned at a slow speed, tearing at one's emotions. Throughout, vibrato and portamento, such useful means of expression, are used to overwhelming effect. That consoles us for a voice that can go out of focus under pressure, so that climaxes are not this Isolde's happiest moments.

Treptow, as Tristan, is disciplined and plaintive, building the role to its Act 3 hallucinations - his Vision is perhaps the most tenderly sung of all - and he boasts a true Heldentenor timbre. Moments when he loses concentration are forgiven for the eloquence of the whole. Klose, such a rounded Brangäne in 1943 (see below), has become blowzy, too much the tragedy queen. Schoeffler is a good, reliable Kurwenal, Frantz a below par Marke. The recording is variable, occasionally distorting, wanting warmth, but the performance grips from start to finish and cannot be ignored by anyone needing to know about the essence of the work. It is an indispensable document of operatic history.

Fourteen years earlier you have to imagine yourself at Covent Garden for Flagstad's debut there, as Isolde, Fritz Reiner conducting, Melchior as Tristan - yet another historical document of considerable importance, now available in amazingly lifelike mono sound. Already in 1936 Flagstad's Isolde was a thing of unequalled beauty, sung with all the vocal verities being obeyed. As I have said, her interpretation is not as considered as it became in 1952 under Furtwängler, but the tone here is in fresher, less matronly state. Although you won't find the psychological insights of Nilsson, Braun or Mödl, nor always the verbal detail, much is achieved with unaffected sensitivity, such as the references to the word "und" in the middle of the love scene. Flagstad's voice is caught with incredible fidelity, more so than in 1952, just as if we were hearing her in the stalls of the theatre. Indeed, the whole love duet is sung by her and Melchior with a bel canto beauty found nowhere else. So is the heartbreaking exchange at the end of the Act.

Melchior's task is made easier by the heinous cuts then current, affecting chiefly his role in both Acts 2 and 3. He sings throughout with feeling but not with the depth or concentration of certain tenors of more modest means. Kalter, a shade passé vocally, is none the less a moving Brangäne. I cannot share the enthusiasm of some for the dry-voiced Kurwenal of Janssen. List brings a sad melancholy to Marke's Lament, but his tone isn't wholly secure. The playing hasn't the refulgence or always the confidence found in many later performances, but Reiner provides the needed discipline, and offers a considered, well-paced reading.

Most of these remarks apply to the EM! mélange of the same performance with one conducted by Beecham from a year later on EM!, although Beecham is the more exciting conductor in Act 2 and Melchior seems in marginally better form. He is still further committed, indeed in pristine state, for the Met broadcast under Erich Leinsdorf dating from 1940; so is Flagstad, and the great Thorborg is there as Brangane - but the poor sound will exclude this from the reckoning of all but the most devoted historically minded Wagnerians. No, if you want a version of this vintage preserving two classic performances -Flagstad sang 182 Isoides, Melchior an incredible 223 Tristans (evidence of their long life, speaking vocally) - the 1936 VAI is the one to have.

My final historic issue, recorded in a Berlin studio in 1943, is the one I reviewed in Gramophone last month. There you will read my paean to Paula Buchner's all-in Isolde, one of the most wide-ranging in interpretative terms on disc, every word and note provided with meaning. She is magnificently partnered by Margarete Kiose, probably the best reading of the role of Brangäne tout court, far superior to her own in 1950 on Orfeo and showing just why I find Lipoviek so madequate. This partnership, allied to Robert Heger's urgent beat, makes theirs an Act ito treasure. Lorenz's 4 variable Tristan, at once exciting, verbally vivid and maddeningly erratic, is predictably best suited to the Act 3 hallucinations. Ludwig Hofmann puts his all into Marke's plaint. Prohaska as Kurwenal is past his best, but full of authority. The sound is variable.

In conclusion

So you can now discern the wealth and breadth of interpretations available on disc - and that's leaving aside the brutally truncated, Bayreuth set of the 1920s, extracts featuring such an Isolde as Frida Leider (who still seems to combine all the attributes found separately in other Isoldes), and the not inconsiderable Helen Traubel - and the many fascinating bits and pieces on the Koch Schwann discs from the Vienna State Opera archives.

There are five performances I would grab from my CD shelves should the flood come and I still had my Discman with me. They are, in my order of preference, Böhm, Furtwangler, Knappertsbusch, Karajan/Bayreuth and Kleiber. With those you have a fair spectrum of interpretations and some superlative singing. But the earth may move for you when listening to Bernstein's eccentric, thought provoking, highly personal account, or Goodall's slow-moving, allenveloping interpretation, or to Barenboim's carefully crafted reading. And you may not want to be without the historic revelation of Flagstad and Melchior in 1936. How lucky to be able to choose from such an amazingly wide spectrum in a work that, to paraphrase Dr Johnson, one can never tire of hearing unless one is tired of opera, or indeed of life itself.