Luciano Pavarotti – requiem for a tenor

John Steane

Sunday, August 20, 2017

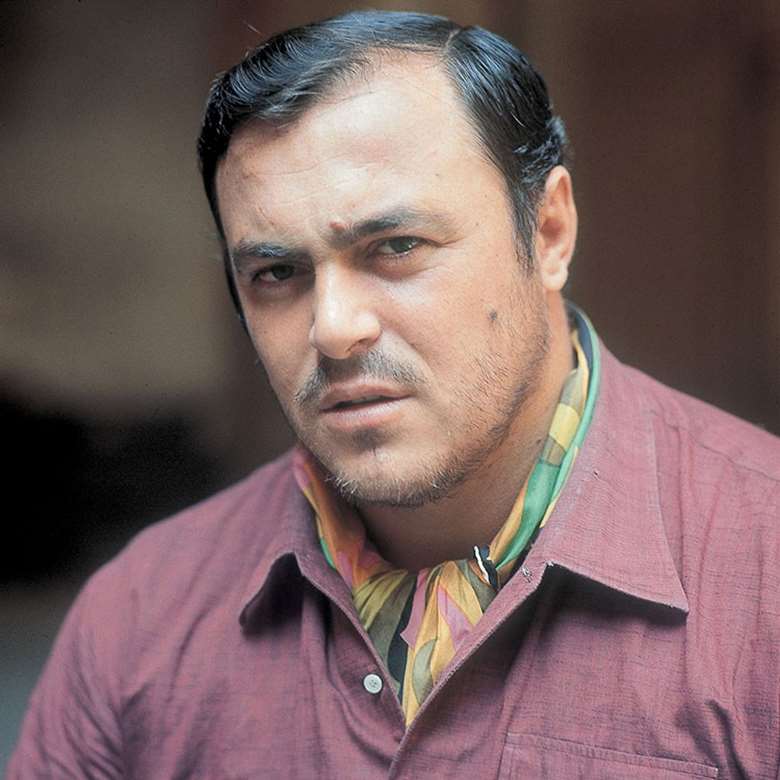

His voice was one of the most remarkable of the 20th century…John Steane pays tribute to Luciano Pavarotti, one of opera’s greatest ambassadors

Toll for the tenor man. Writing now on the morning of his funeral in Modena, it occurs to me that not since Caruso’s funeral at Naples in 1921 has the death of an opera singer so evidently touched the world at large. His passing bell will have sounded over the past few days in countless minds doubtless to the accompaniment of another sound, his own voice rising perhaps in the sad tune Puccini wrote avowedly to make the world weep. ‘E non ho amato mai tanto la vita’. And now, alas for Luciano. All that remains are the saddest words in the operatic vocabulary: ‘mai più’. Nevermore.

Except of course that it’s not all. His recordings are many; and, on the whole, compared with several of his own time and many more of the past, they do him pretty fair and comprehensive justice. Not much that he sang is not there in those readily available CDs, and they catch him as to the life.

But let’s not be in too great a hurry to break the commemorative silence. At such times it’s good to listen inwardly, search round a little and wait. The voice will come in its own good time though you can never tell what form it will take: what the medium, the music, will be. Just now it came to me in a song, with piano accompaniment, words before music so that I had to think a moment to place it. ‘I tuoi baci non cerco, a te non penso, sogno un altro ideal…’ Well, there’s a strange one. Not appropriate at all really. Tosti’s ‘Non t’amo più’. And Pavarotti’s voice is overlaid by another’s: I have first to wipe away the froth and over-boiling passion of (do we remember this name?) Aureliano Pertile. Pavarotti venerated him, a tenor of the inter-war years (‘When you are feeling dim and down in what you are working on, then you go to Pertile and the life will come back,’ he said). But the comparison which the memory of that song enforces shows how Pavarotti’s musical style has refined upon the older singer’s. In fact he has gone back beyond Pertile to a purer tradition of Italian singing in which passion was less disruptive and overt. His style is altogether more reflective, and by reducing the operatic con forza of its delivery he comes much nearer to the true nature of the song: a bitter-sweet lyrical confession of lost love, the easy swing of its melody as the refrain gets under way suggesting that the broken heart will soon enough be mended.

Phrases jostle and collide as the voice starts to lodge in the mind. The Italian popular songs of Caruso’s time come unbidden – ‘Mattinata’, ‘Core ingrato’, ‘O sole mio’. On the morning when the news of his death took precedence on the radio over politics and sport, they played snippets, principally of Puccini: ‘Che gelida manina’, ‘E lucevan le stelle’ and of course the eternal ‘vincerò’ from ‘Nessun dorma’. But he was a Verdi singer too, and if there was one composer he could claim as his own it was Donizetti. In Verdi perhaps we think first of the sword-and-chandelier rattling top Cs of Il trovatore, then more typically of Riccardo’s brave gaiety in Un ballo in maschera or of his unexpectedly tender ‘Celeste Aida’ with its piano last B flat.

Or perhaps it will be the Requiem that comes to mind. In that case another comparison may be evoked. Beniamino Gigli was so much the tenor of the Italy in which Pavarotti grew up, and the tenor part in the Requiem bore his image. With him the entry in the Kyrie would always bring a thrilling tingle of recognition, and the mystical ‘Hostias’ had the other-worldly purity of an alto choirboy. But Gigli would also scatter his aspirates liberally over the ‘Ingemisco’: ‘Qui-hi-hi Ma-ha-riam…’. Pavarotti would have none of that. Again, as with Pertile in the song by Tosti, the comparison with Gigli in Verdi shows Pavarotti as an exponent of refinement in the development of stylistic habits in Italian singing.

But that’s enough of this internal listening and reminiscing. The ear craves sound. The shelves almost groan under the weight. There are, for a start, all those collections of recycled arias that (as reviewers certainly) we probably cursed at the time but which now prove their usefulness as quarries. Here’s a solo from Guillaume Tell with its reminder of the solid underlay which makes the Cs and B flats doubly exciting in context. Then for Cs, here are the famous nine in La fille du régiment – and memories of our colleague Edward Greenfield, present at the recording session and reporting how, so far from nine being the limit, the piece was repeated over and again without a murmur of complaint from Pavarotti.

Or we could be systematic and begin at the beginning. If so we might search in vain for the original first recording of all. It was an obscure little 45rpm, now a collectors’ rarity, of which Philip Hope-Wallace wrote in the Gramophone of November 1964: ‘He is a pleasant and useful artist, still, I would say, in the making’. Pavarotti had that record withdrawn, but it by no means disgraces the singer and the Bohème aria alone might well have alerted someone in high places. As it was, and perhaps all to the good, most of us made Pavarotti’s acquaintance on record some three years later in his role opposite Joan Sutherland in Beatrice di Tenda. ‘Not exactly a delicate or imaginative artist,’ wrote Andrew Porter, ‘but he is not a brute.’ That was praise indeed, and he added that the voice was ‘firm, unstrained, even lustrous’. Some still find his best singing in the early records till about 1975. Certainly there is a freshness of voice and freedom of production which in later years such listeners found to appear somewhat constricted. The later years saw the extension of his repertoire into the heroic Verdi roles of Manrico, Radamès and eventually Otello. If we sample that again, we find it scrupulously sung and genuinely felt, but, as Hope-Wallace said of the inconspicuous first, ‘still in the making’.

For myself, the mind inevitably goes off on a more personal track, to the day when I met him: a July afternoon in Pesaro with a heavenly view out over the sea. We sat at a small table with cheese and wine (‘Ees good?’ he asked. ‘Is very good,’ I said. ‘Ees NOT good!’ And he called, Otello-voice in action, for a bottle of something better). We talked about tenors of the past. Unusually for an Italian, he expressed a deep admiration for Jussi Björling. Caruso he saw as the great original in the modern tenor business. Martinelli? He wrinkled his nose. ‘It’s an acquired taste,’ I conceded, and he said that he must try again. He had recently been recording I Lombardi, and the tricky subject of La forza del destino was raised. He shared the common superstition about that opera – a friend had died during a performance. He was keen for suggestions about repertoire. Half in earnest (and with explanations) I suggested what I called Il sogno di Gerontio, and then immediately realised that it wouldn’t get past the starting-post if ever he went so far as to look at a score. There he would see Gerontius’s first words and that would be enough: ‘Jesu, Maria – I am near to death, and Thou art calling me’.

Pavarotti died on September 6, 2007, but it was by then a long time since he had been part of the regular fabric of musical life. It was a natural and gradual process of withdrawal, and if the year 2000 suggests itself as the date with which the process began then that is primarily for purposes of convenience. Since (roughly) then he has been that anachronistic phenomenon, the ‘living legend’. And the legend was that of the genus ‘Italian tenor’: he embodied it.

The Italian tenor was a creation of the 19th century that came into its kingdom in the 20th. Or, to use a less lofty image: for that hundred years, the human zoo had its prize exhibit of the species to point to, which it did with a mixture of pride and amusement. Over the period there were essentially three specimens: in turn, Caruso, Gigli and Pavarotti. Caruso, prototype and archetype, amazed the world with the richness, power and passion of the voice which all could hear on the fabulous phonograph. It created a kind of awed wonder, which his death confirmed: the price exacted, people felt, for a superhuman gift. ‘Of course,’ the grown-ups assured me when I first became interested as a boy, ‘his singing killed him’. Gigli, coming after him, did not have to be taken so seriously. He was a natural, and Nature would not punish him for his abundant expenditure of such a gift. But he was a chubby little fellow, with nothing of the heroic about him. And he sang the songs of the ice-cream seller. Gigli inherited an awesome throne and made it democratic, singing to gallery queues and from hotel balconies. It came then to Pavarotti in a world where royalty had taken a tumble. His figure, his trademark handkerchief and his prodigious high notes commended him to the world at large. In the interval since Gigli’s time there had been no shortage of candidates but the world, grown accustomed to superstars, was perhaps unconsciously waiting for one larger than life. Nobody could have filled its expectations so well as he did.

But there is a world within this world, one which reckons to know and judge. The greater part of this comprises the ‘serious’ musician and the ‘general’ (but also ‘serious’) musical public. For many of these people over the hundred-year period in which we are now placing Pavarotti, the Italian tenor (as a species) has been a sideshow. The musical establishment prizes the symphony orchestra, the string quartet, the concert pianist, the choirs and the singers of what it calls art-song. The operas of Mozart and a select few among other composers have been admitted, but to Caruso (for instance) and what he represented many were indifferent and some hostile. Gigli they would ignore. Pavarotti they would good-humouredly acknowledge. But by then the times they were a-changing, and opera (even the despised bel canto school) was gaining ‘serious’ musical recognition. Of the century’s three Italian tenors, Pavarotti stood the best chance of ‘serious’ musical acceptance.

The other element within the world of knowers and judgers is what we may call the voice-people. They (and I write as one of them) are institutionally suspicious of popularity. Caruso has been a long time dead, and that is something in his favour as far as these people are concerned, but Gigli (who did for himself still more in their view by going into films) was never a connoisseur’s singer. Pavarotti too: the world seemed to think that he was what the word ‘tenor’ meant and the voice-people knew better.

And indeed Pavarotti is very far from being ‘the last word’ or the definitive exponent of the tenor’s art. If you take as a test-case some standard aria such as ‘Ah, si, ben mio’ (Il trovatore) or ‘Quando le sere’ (Luisa Miller) and organise a parade of leading tenors on record, Pavarotti’s version is unlikely to emerge as the best or as having some particular characteristic that places it among the most memorable or distinctive. One leading vocal expert, the German critic Jürgen Kesting, has gone so far (in his book Luciano Pavarotti: The Myth of the Tenor, 1991) as to argue that the Pavarotti phenomenon is essentially a creation of publicists. In this analysis, the press has colluded with the record industry to promote a peculiarly marketable figure whose true eminence has been magnified out of all proportion, even within his own specialised segment of the musical profession.

At best this can be accepted only as a part-truth. ‘Pavarotti Dies’ was writ large on that Thursday’s billboards, not just the front page of the papers themselves. ‘Fischer-Dieskau Dies’ is something I do not expect to see on those same billboards. If the musical considerations were uppermost, there would probably be general agreement that the melancholy distinction should belong to Fischer-Dieskau. It’s true: the billboards almost certainly reflect ‘Nessun dorma’ and the World Cup rather than anything which took place in an opera house.

But all this, this niggling resentment and insistence on cutting down to size, flies (as far as I am concerned) in the face of the experience of hearing him. I recall my own first time. It was at the Covent Garden La Sonnambula of 1965. In the interval, my friends wanted to talk about Sutherland and I remember trying to interpose with ‘But what about that tenor? Isn’t he something a bit special?’ And yes, yes, they said, he’s very good, and back they went to Sutherland. But he was more than very good. ‘A bit special’ was putting it mildly. On the other hand, how to substantiate the point? He was a graceful stylist (and at that time I would have had standards in mind set by records of Fernando De Lucia and Tito Schipa in the duets). But the prime quality had to do with the purity of the voice. A negative definition is always a second-best, but I have to put it this way: there was in his tone no admixture of breathiness or wear, no raw edge, no point at which a rough or rattly or tinny sound would obtrude. This is rare. It is rare enough to find it in a young voice, as Pavarotti’s was then (though he would have been 30), and much rarer, in fact utterly exceptional, to find that a singer retains this purity throughout a long career. But Pavarotti did just that.

I think the last time I heard him sing was the concert at Modena’s opera house to celebrate the 40th anniversary of his debut there. Gheorghiu and Alagna, Carreras, Scotto and Raimondi were among the guest artists. Pavarotti’s contributions were restricted modestly to a part in the Quartet from La bohème and duets from Tosca and Aida with Carol Vaness. I wrote at the time: ‘He characterised tenderly and humorously; his voice was pure and steady, gracefully modulated and still capable of a ringing climax’. And, note, ‘pure’.

This was no invention of publicists. He was by the standards of any age exceptional in the quality of his voice, the nature of his vocal resources and the technique and good judgement which enabled him to keep them in use and in such good condition for so long. One cannot help but think also of the man. Caruso, with his cartoons and practical jokes, Gigli with his chubby eagerness, both had something of the clown about them; something touchingly dignified too. Pavarotti comes to mind now as a man who in himself invited caricature – we think of him with a smile. But that is only a first thought. He was a man of thought and feeling, aware (as in his venture for the children of Mostar) of wider responsibilities. He was clear-minded, accomplished (for one thing, speaking fluently in a language not his own), and rather remarkably graceful. Essentially, it is all there in his art. I have just played his solo recording of Faust’s ‘Giunto sul passo estremo’ from Mefistofele (it somehow seemed appropriate). It was freshly moving to hear the voice, its tones so even in their vibrations and so justly proportioned, the high and low, the loud and soft. How good too to hear (slyly observed as a test) how those three descending notes on ‘Ah’ are sung legato. But, beyond all that, this is a felt, thoughtful account, responsive to every suggestion of music and of words. This was the artist, and the artist relates to the man. Today we honour both.