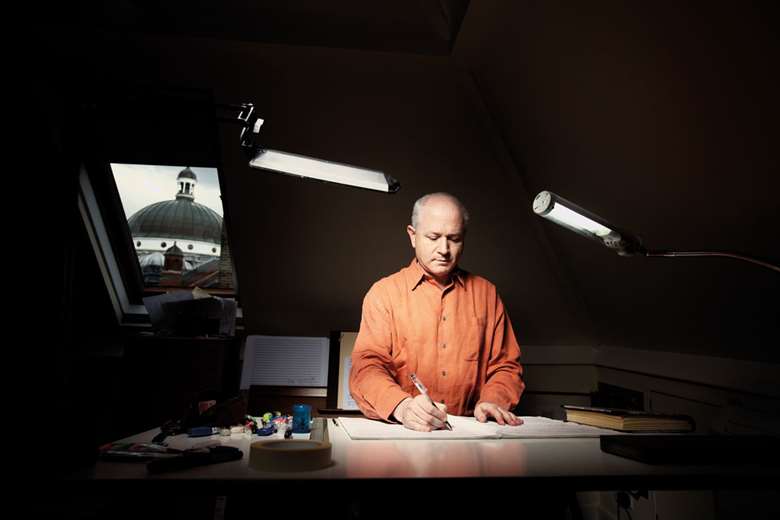

Contemporary composer: Sir George Benjamin

Gramophone

Friday, September 1, 2017

Geraint Lewis explores the acutely imagined sound worlds of the winner of the 2017 Gramophone Contemporary Award

That astonishing scene towards the end of George Benjamin’s Written on Skin – when Agnès is forced by her husband to eat the cooked heart of her murdered young lover – must surely count as one of the most spine-chilling moments in the history of opera. The brilliantly etched text by Martin Crimp allows us, as stunned spectators, to sense the unspeakable horror about to happen while simultaneously realising that Agnès herself is momentarily ignorant of what she’s eating. Benjamin’s equally forensic music fits every word like a glove and succeeds in bridging the sudden dawning of Agnès’s absolute hell, as it turns into a gleam of inner redemptive power, with seamless eloquence: ‘No – no – nothing – Nothing you can do – Nothing I ever eat / nothing I drink / will ever take the taste of that Boy’s heart / out of this body.’

Since its premiere at the 2012 Aix-en-Provence Festival, Written on Skin has enjoyed a triumphant progress around the world, and in January this year returned to the Royal Opera House for a revival that saw capacity crowds for six performances. Such statistics are rare in the supposedly specialist world of contemporary opera – and in Benjamin and Crimp’s case this is achieved without any artistic or cultural compromise of their single-minded vision. Their journey together started with the one-act ‘lyric tale’ Into the Little Hill at the Paris Autumn Festival in 2006; and a new recording about to be released on Nimbus Records, featuring Benjamin conducting his long-term colleagues Susan Bickley and the London Sinfonietta, potently underlines the creative synergy which promises so much for the third collaboration, due to be introduced at Covent Garden in 2018. It is both telling and reassuring to know that Benjamin has managed to clear his diary for the whole of 2017 in order to concentrate completely on this exciting new operatic phase in his career.

Benjamin today is softly spoken, modestly mannered and carefully considerate. During my last year at Cambridge in the late 1970s I well remember that word spread like wildfire of a new composer student who would soon set the musical world alight. On a brief meeting then he seemed exactly as he does now – the very antithesis of a wild compositional prodigy. Appearances can be so deceptive! But as quickly as summer 1980 his orchestral Ringed by the Flat Horizon took the Proms by storm, with Benjamin becoming the youngest composer ever to have a work premiered there. His musical pedigree was now examined thoroughly by the world at large and initial training from Peter Gellhorn while still at Westminster School, early entry into Messiaen’s class at the Paris Conservatoire and further study at Cambridge with Alexander Goehr and Robin Holloway confirmed on paper what the ear heard so eloquently in the meticulous scoring, sustained structure and sheer aural brilliance of this orchestral score, inspired by an image from TS Eliot’s The Waste Land.

As Ringed by the Flat Horizon began its steady progress into the large-orchestral repertoire, so a couple of smaller canvases amply consolidated its promise and revealed the sheer depth of Benjamin’s technical finesse, detailed imagination and harmonic ingenuity. A Mind of Winter was first heard at the 1981 Aldeburgh Festival and sets Wallace Stevens’s The Snowman with delicious filigree textures and an unerring sensitivity to textual nuance. With At First Light in 1982 for the London Sinfonietta and Simon Rattle, Benjamin turned to visual imagery in this translation into sound of the magical, light-infused Norham Castle, Sunrise by Turner (which can be seen in Tate Britain). Here, the composer’s virtuosity is further enhanced in its dazzling treatment of a very specific instrumental grouping just as it unfolds a seemingly spontaneous but satisfyingly grounded structure.

These early years saw Benjamin embarking on crucial partnerships with a publisher – Faber Music – and recording company – Nimbus Records. That these remain unbroken to this day after nearly 40 years speaks volumes for the trust, loyalty and dedication shown by each to the other. Another side of Benjamin’s career, which both have continuously encouraged, is that of his exceptional performing skills as pianist and conductor. The coruscating Piano Sonata written in Paris in 1977‑78 featured on his debut LP for Nimbus and he was soon conducting the London Sinfonietta on its successor CD. Such multitalented composers are not of course unique – one thinks immediately of Knussen, Adès, Huw Watkins and Ryan Wigglesworth – but there is, nevertheless, a special quality to the creative symbiosis Benjamin makes of his interconnected abilities. In the early days, indeed, such prodigious talent led inevitably to exaggerated comparisons with Benjamin Britten – which Benjamin himself deflected very deftly. But even though he has explored as conductor the works of many composers close to his own spirit with great insight – Berlioz, Debussy, Ravel, Messiaen, Boulez, Harvey and Grisey spring notably to mind, among many others – he has tended of late to harness his career in this area towards the expert interpretation of his own scores.

What today’s unquestioned fulfilment of very early promise demonstrates beyond doubt, however, is that Benjamin needed nerves of steel to survive – unimpaired – into this rich maturity. The darker underside of undue and premature expectations can be a lack of time and space to develop at the speed appropriate to an individual’s unique creativity. In learning the hard way, Benjamin managed to turn one or two difficult commissions into a deeper understanding of the gestation period needed; and when Sudden Time finally emerged in 1993 (having been begun in 1989), its fulminant energy and explosive impact confirmed that the wait had been worth it. Here, then, was a new, tensile power feeding a heightened freedom of emotional expression: qualities quickly concentrated in the lyrical impaction of the Three Inventions (a densely layered triptych premiered at the 1995 Salzburg Festival) right down to the iconically graphic Viola, Viola (1997), back through the pair of large-chamber-orchestral Palimpsests (2000-02), the pivotal set of choreographic-orchestral Dance Figures (2004) to the abstract drama of Duet (2008) for piano and orchestra, featuring Pierre-Laurent Aimard as collegial soloist.

Tracing Benjamin’s slow and careful evolution is to follow a series of sudden epiphanies in which new compositional territory emerges hand in hand with a freshly minted world of sonority. Nothing is seemingly off-limits. From the IRCAM-originated synthesised panpipes of Antara (1987‑89) we move immediately into the arcane sound world of the Elizabethan viol consort as the perfect backdrop to a haunting setting for mezzo-soprano of Yeats’s ‘Long-Legged Fly’ under the eloquent title Upon Silence (1990). The small ensemble of Into the Little Hill crackles with exotic cimbalom, just as the full orchestra of Written on Skin resonates atmospherically with the ghostly halo of a glass harmonica; other telling examples proliferate. Nothing by Benjamin is written without a consummate sense of balance, yet his later music also allows the unexpected emergence of a visceral and violent agony which tears apart any outward sense of quiet decorum. The latest score, Dream of the Song (2014‑15), is a sensuous exploration of the interstices between words and musical expression which stretches Benjamin’s palette to its kaleidoscopic extreme in juxtaposing countertenor, female voices and full orchestra.

With an English sensibility that he finds rooted in the fantastical world of Henry Purcell, George Benjamin is also a composer of truly international stature. His initial immersion in the French ambience of Messiaen and Boulez found a reciprocal responsive home there, but without any limiting sense of partiality. Linguistically, Benjamin delves deep for an intuitive reconciliation of opposing tensions which he has to forge anew for each new work. In saying that there is possibly no more gifted or significant composer working anywhere today, any sense of exaggeration is tempered by the sumptuous reality of his output to date.

This article originally appeared in the April 2017 issue of Gramophone. To explore our latest subscription offers, please visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe