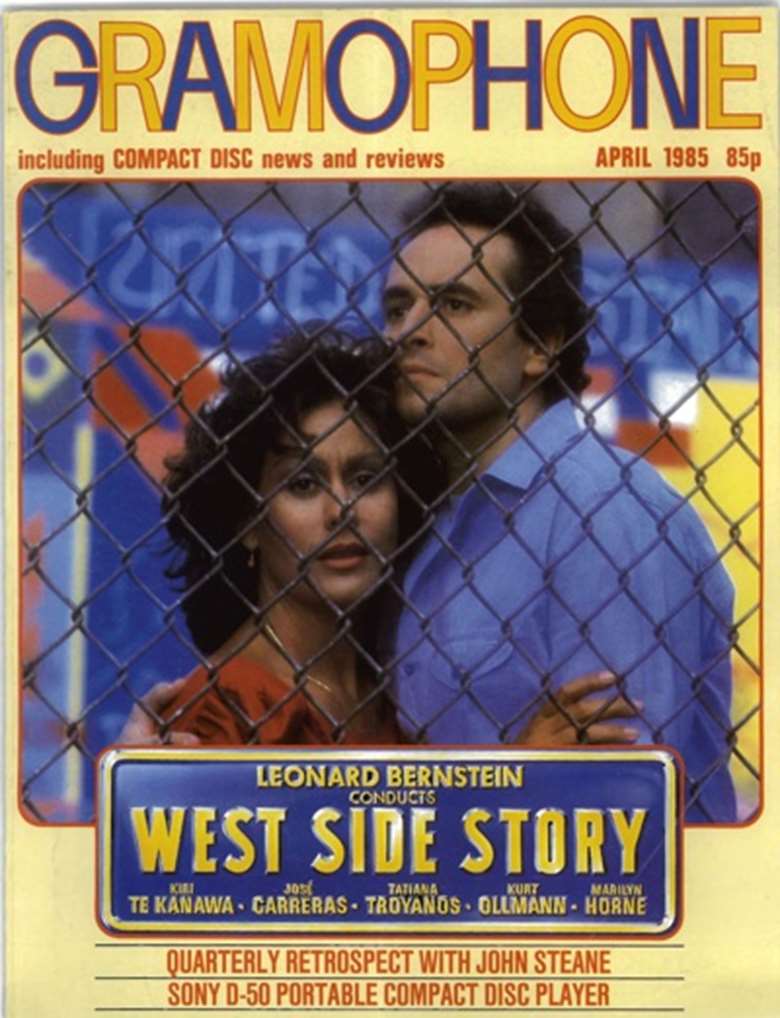

Bernstein's West Side Story

Gramophone

Wednesday, August 26, 2015

A session report by Humphrey Burton first featured in the April 1985 edition

For the DG recording of West Side Story, made in September 1984 in New York, Leonard Bernstein drove down from his house in Connecticut... Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, singing Maria, flew in from the south of France where she'd been studying the score and vacationing with her family... Jose Carreras (Tony) arrived from Verona where he'd been singing in Carmen... and Tatiana Troyanos-the Anita of the recording-took a cab from her East Side apartment. She grew up on the West Side, however, near those tenement blocks whose fire escapes form the unforgettable backcloth to West Side Story. It was, to say the least, a highly unlikely cast for what is basically a Broadway show. BBC cameras filmed the week-long recording sessions, rather as they did two decades ago for Solti's Ring; what follows are some of my impressions and my conversations with the artists.

"l'd always thought of West Side Story in terms of teenagers," Leonard Bernstein told me, "and there are no teenage opera singers, it's just a contradiction in terms. But this is a recording and people don't have to look 16, they don't have to be able to dance or act a rather difficult play eight times a week. And therefore we took this rather unorthodox step of casting number-one world-class opera singers. I suppose the only foreseeable problem was that they might sound too old - but they don't they just sound marvellous!" Bernstein is specific about the reasons for his enthusiasm. "Kiri singing the part of Maria is a dream. Maria is a Puerto Rican girl and there's a dark colour in Kiri's voice, coming from the Maori blood, I suppose, that is deeply moving and just right for this part. And yet when she has to sound girlish and lyrical in the high registers, it's exactly what I want."

There are other changes of emphasis on this recording. If you know the music from the Broadway cast recording or the film soundtrack, you'll be surprised by the slow tempo for "I feel pretty", the Act 2 opener. "In the theatre," says Bernstein, "it is always played as brightly as possible to dispel the dreadful shadows at the end of Act I which closes with two corpses on stage. Ugh' 'I feel pretty' is there to say to the audience 'Don't despair, Act 2 is going to have some up moments.' But for the recording, we don't have to do that, and we can take the tempo in which I really dreamed it, which is rather elegant and lyrical."

Kiri arrived in the studio to record literally voiceless, suffering from the New York disease known as 'Airconditioningitis'. Her huskiness an hour later was just what the composer desired, while "Kiri just ate that up" was his comment on her interpretation.

The new West Side Story is not just different in terms of tempo; it is also, at 75 minutes, much longer than the two previous versions on record, both of which were heavily cut to fit on to single LPs. The slow and touching introduction to the duet "One hand, one heart", with a melting clarinet solo, is a case in point. Indeed, the whole song makes more impact than in the theatre ; here is music which, says Bernstein, "exists on the brink of a precipice of an abyss of sentimentality: the slightest little push and you're just dead ". But artists of the calibre of Te Kanawa and Carreras - "whose main reason for existing is their singing" can bring out the gravity of the dramatic situation in which the star-crossed lovers are secretly exchanging marriage vows without benefit of a priest. "If that song is any less than 100 per cent, well it sounds simply sappy. But yesterday 's final take just destroyed me."

Bernstein is much given to extravagant expressions of his feelings-a characteristic which tends to make we British a little wary of him. Three years ago, BBC's Omnibus taped his rehearsals with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducting Elgar's Enigma Variations, and the preliminary lack of rapport between conductor and players was painfully evident. Not so on Bernstein's home ground, however, and not so in Bernstein's own music. "You just love that energy and that brilliance," Tatiana Troyanos told me; "there must be a million thoughts that go through his mind every minute. I find it so exciting; he's absolutely magnetic ".

For Te Kanawa, who has loved West Side Story since she was a girl and actually recorded a number from it when she was only 19, working with Bernstein for the first time was a hectic experience. "The funniest thing of all was when he suddenly stopped conducting and said 'That's the tempo, that's it. ' And I laughed, because it was like having Mozart with you, you were getting it from the master himself. He's a man of many emotions. You can see his moods, his frustration s, his happiness, his wanting to perform to people. That's the thing that makes the man interesting. One is constantly trying to read him, but he's on another plane!."

José Carreras praised Bernstein's conducting technique: "His every movement is music. He tells the performers what he wants with his gestures, with his eyes, with his body. Nobody in the world is able to do it like him." Mind you, there was no time for mutual back-slapping during the four days of the sessions. This wasn't a typical 'cast recording' based on an already-existing theatre team: everybody was recruited especially for the job and moulded, literally over night, into a musical team by David Stahl, a rising young American conductor who was in charge of the 1980 Broadway revival of West Side Story. Apart from Kurt Ollmann, singing Riff (who will be singing Pelleas at La Scala for Abbado in 1986), there are a handful of singers who worked with Bernstein in his opera A quiet place and others who come from that Broadway talent pool described by Bernstein as New York gipsies: "They sing anything in any range; they will dance tap and take ballet lessons; they have this inexhaustible energy." On the record, you hear their vitality in the chorus numbers of the Jets and the Sharks, in the slapstick of "Gee, Officer Krupke" and in the witty byplay which accompanies "America". Matched and spurred on by Louise Edeiken's Rosalia, Tatiana Troyanos reveals a delicious sense of humour in that glorious show-stopping number, which throws into higher relief the tragic intensity of her performance in "A boy like that", the sombre duet in which Anita, inspired by Maria 's simple eloquence, switches loyalties and allows the lovers their night together. This duet is one of the truly operatic highlights in a work which nevertheless resolutely defies categorization. Literally half the music is dance music or music with speech over it.

"...they looked more like conjurors or acrobats than musicians as they darted mercurially back and forth from timpani to maracas..."

But there is a chorus and Bernstein told me that he reckoned half of them had performed West Side Story somewhere or other in recent years, some in a recent French production, others in the Broadway revival. The orchestra was a pick-up affair, most of them session-players who thrive on Pepsi-Cola jingles. "Only three of them played in the original 1957 production but I would say I have worked with at least half before, though not as a group. The First Flute, for example, Julius Baker, was my first flutist at the New York Philharmonic for 10 years (he's retired now). And we have my First Viola from the Philharmonic. He wanted to play it so badly that he called and asked if he could and I said there weren't any violas in the orchestra ofWest Side Story and he said 'Alright, would you let me sit in the second violin section?'"

The absence of violas was a direct result of the limitations imposed on the composer by the size of Broadway theatre orchestra pits. Thirty-two players were squeezed into the Winter Garden, and Bernstein economized on space (he needed it for the brass and all the Latin-American percussion) by omitting a harp and the violas ("cellos playing high can do everything violas do more brilliantly"). For the recording the string section was enlarged, so that there's no hint of the scrawny string sound which disfigures many musicals on record. And the woodwind section was expanded from the original five players to 13, to eliminate most of the doubling. The two percussion players insisted on keeping to the original hair-raisingly complex distribution of instruments, even though they looked more like conjurors or acrobats than musicians as they darted mercurially back and forth from timpani to maracas, from cowbells to police whistle.

Performing West Side Story at all was something of an editorial miracle. Bernstein had never conducted it in all its three decades of worldwide success (it has been translated into - amongst many other tongues - Japanese, Serbo-Croat, Finnish, Russian and Hungarian, twice!). This is hardly surprising since he has never conducted a theatre performance of any of his other works for theatre, On the Town Candide, Wonderful Town or Mass . But it did lead to complications. In the pit, Bernstein told me, "conductors use a piano/conductor vocal score. It is marked up with cues of which instruments are playing and looks like a road map with different coloured pencil arrows indicating cuts and transpositions and whatever. But I had to have the full score to conduct the recording and so I did a lot of editing, picking up missing dynamics, correcting inconsistencies and so on. I don't know how this piece has weathered three decades this way! It is a big, long score and is of a certain complexity, so editing took a lot of time." Indeed, some details were still being sorted out at the sessions. "Only two mambos here," called the disembodied voice of John McClure the recording producer in the control room. He was instructing orchestral players to shout the word "mambo" during the electrifying Dance at the gym. "Why is it only those?" asked the maestro at the rostrum. "None of it is in the score," replied McClure. ''I'm just going by the original-cast recording."

McClure has made literally hundreds of records with Bernstein, going back to the days when McClure was Director of the CBS Masterworks label. His cheerful laid-back manner was in sharp contrast to the sober style of the DG engineers led by Karl August Naegler who had flown in from Germany complete with equipment to make the recording. Bernstein called McClure "Great White Father" and referred to him as "my telephonic superior", acknowledging that at the session the producer is the one who has to ensure that every fluff or "fish" is covered and every instrument audible.

During the week Bernstein listened to all the takes, sometimes going back to record new pick-ups and versions at the next session; he made a preliminary choice for the process of editing; months later he would listen to the edited assembly submitted for his approval, and then it was he who played the Great White Father.

A father figure he certainly is, and literally so for the young actors who speak the dialogue lines of Tony and Maria. Alexander Bernstein and Nina Bernstein are their names, only son and younger daughter of the composer; both professionals and both excellent.

The recording process for any composition is generally tense and often exhausting. But these West Side Story sessions were exceptionally exhilarating and immense fun to be at, as you can see for yourselves in our Omnibus film. For Bernstein himself the experience was a voyage of discovery, "very rejuvenating and enlightening. I've been feeling very young and identified with this 28-year-old piece , and feeling rather the way I felt when I was writing it. II's so funky. I'm so proud of the way it seems to stay young. This may sound self-congratulatory but it sounds as though I just wrote it."