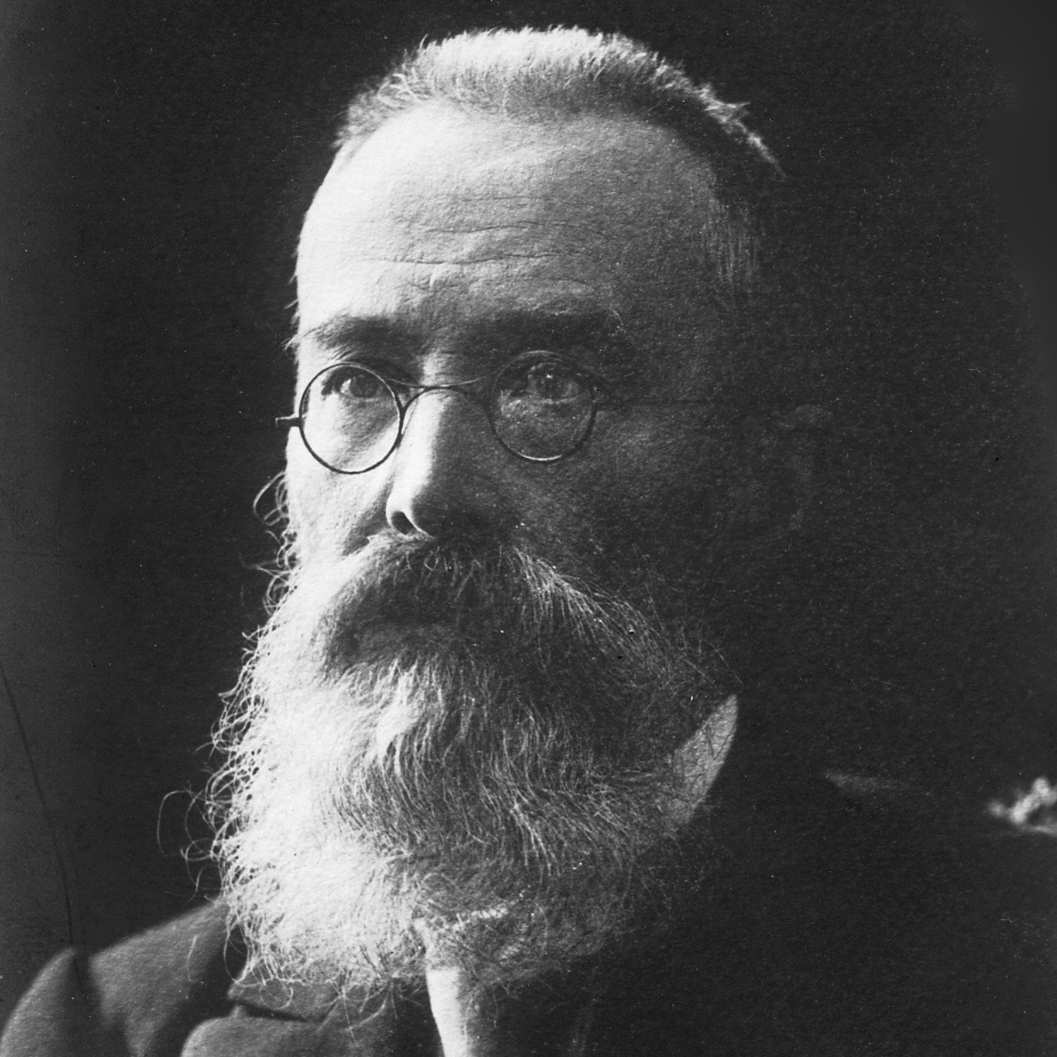

Rimsky-Korsakov

Born: 1844

Died: 1908

Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov

Despite the meagre amount of his music heard regularly today, Rimsky-Korsakov’s place in Russian music cannot be overstated.

Rimsky-Korsakov: a biography

Compared with the music of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov, a meagre amount of Rimsky’s music is ever played. And his operas, the works which Rimsky believed to be his finest achievements, are all but unknown. Yet his place in the development of Russian music cannot be overstated for, apart from his own work, he was an important teacher, numbering among his pupils Glazunov, Liadov, Arensky, Ippolitov-Ivanov, Grechaninov, Myaskovsky, Prokofiev and (privately) Stravinsky.

From a wealthy, aristocratic landed family where music was part of the fabric, Rimsky was discovered to have a natural talent for the piano at an early age but all his ambitions were focused on joining the navy like his elder brother. Instead of a conservatory, he entered the Naval School in St Petersburg in 1856 but took piano lessons and began to form ideas for composition while he was there, enthused by performances of various operas – especially Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar and Ruslan and Lyudmila. He was introduced to Balakirev and, like many another, fell under his charismatic influence, cajoled into attempting a symphony. In time, Rimsky would become the fifth (and youngest) member of the group known as ‘The Mighty Handful’ – Cui, Mussorgsky, Borodin and Balakirev himself – who were to shape the force of Russian nationalism in music.

In the meantime, the call of the sea was more powerful and on graduating in 1862 he joined the clipper Almaz for a voyage that kept him from St Petersburg for two and a half years. On his return, Balakirev conducted a performance of Rimsky’s First Symphony in December 1865 which, as much as anything, finally determined him to make music his life. He was still considered a gifted musical amateur by the circle in which he moved – and he was certainly musically under-educated – when Cui asked him to help to orchestrate an unfinished opera by Dargomïzhsky (The Stone Guest). This proved to be a formative experience, one which provided a vivid and intense lesson in the arts of dramatic construction and orchestration.

His astonishment can be imagined then, when, at the age of 27, he was offered the post of professor of composition at the St Petersburg Conservatory. He remained on the faculty from 1870 until his death. As he himself said, ‘I did not know at that time how to harmonise a chorale properly,’ confessing that he had ‘never written a single contrapuntal exercise in my life, and had only the haziest understanding of strict fugue; I didn’t even know the names of the augmented and diminished intervals or chords’ – irrelevant terms for the layman, perhaps, but basic considerations for a teacher of composition. Instinct alone had got him this far.

From here on, Rimsky-Korsakov’s history is one of increasing influence as a teacher and administrator, parallel with his development as one of Russia’s most celebrated composers. For, by the mid-1870s, the basic characteristics in all his music had flowered – a love of fantasies and fairy-tales, and a dedication to nationalistic music coloured, like the work of the other four of ‘The Mighty Handful’, by orientalism. Overwork brought him to the verge of a nervous breakdown in 1889, to be followed, after a relapse of two years, by a creative outburst which established him firmly as the most famous of The Five, whose power in the musical world of St Petersburg was absolute.

Rimsky, though, was no dictator. Indeed, when the conservatory students rebelled against the authorities in 1905, Rimsky took the side not of the establishment but of the students and was dismissed from his post for his pains. It made him something of a hero. Glazunov resigned in protest. When he was recalled and made director, Glazunov immediately reinstated Rimsky. His last appearance abroad was in 1907 – in Paris, where he conducted two concerts of Russian music put on by Diaghilev. His last work, the opera Le coq d’or, was banned by the censor – it dealt with the bungling administrators of Russia and a stupid Tsar – but he died of angina pectoris before the situation was resolved.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.