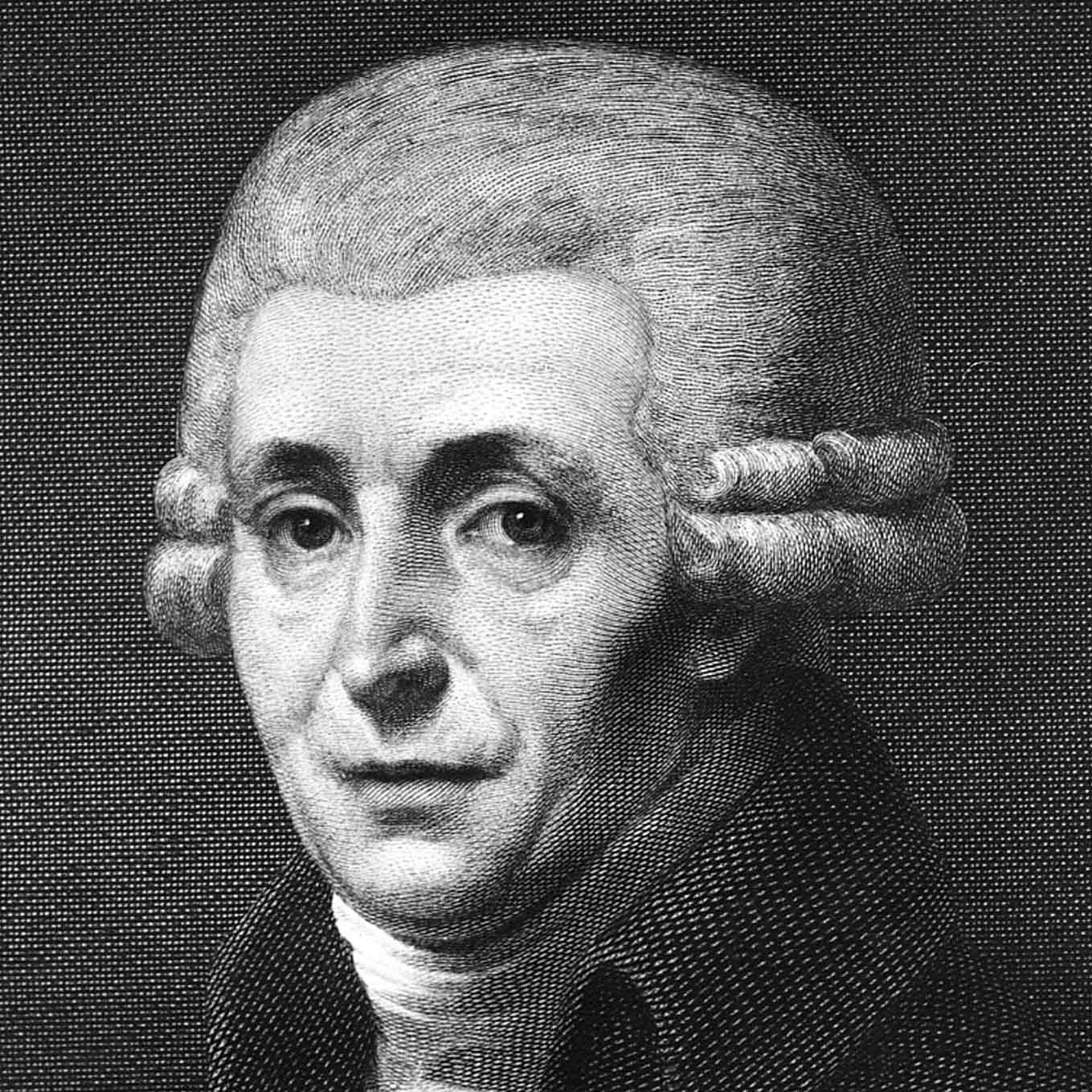

Haydn

Born: 1732

Died: 1809

Joseph Haydn

Haydn was among the most prolific of all great composers and he wrote in every form: 104 symphonies, nearly 90 string quartets, 62 piano sonatas, dozens of concertos, oratorios, masses and choral works, 23 operas, many songs and a huge amount of chamber music. His variety, unpredictability, wit, quality of invention and genius for musical construction put him head and shoulders above his contemporaries.

Explore Haydn's life and music...

Top 20 Haydn recordings

Twenty outstanding Verdi recordings, featuring René Jacobs, Claudio Abbado, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Alison Balsom, Alfred Brendel and many more... Read more

Haydn - the poor man’s Mozart?

In the two centuries since his death Joseph Haydn has been scandalously underrated, argues Richard Wigmore... Read more

How can anyone not like Haydn?

Philip Kennicott on discovering a rare, benighted breed – the Haydn-hater... Read more

Biography

Haydn’s father was a wheelwright and the village sexton. Joseph was the second of his 12 children. His brother Michael, born five years later, also became a composer. Where did the music come from? Haydn’s father had taught himself to play the harp by ear but otherwise, like Handel, there was nothing in his ancestry to indicate a musical career. His first lessons were from a cousin, a choral director, and he was only eight when admitted as a chorister to St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna.

After leaving the choir when his voice broke, he was thrown back on his own resources, borrowing money to rent an attic where he could practise the harpsichord. He made a thorough study of CPE Bach’s keyboard works, read as much musical theory as he could absorb and had a few lessons from the then famous Nicolò Porpora, an Italian composer who was living in Vienna. His first compositions began to get noticed and he was engaged as music director and composer to the Austrian Count Maximilian von Morzin at his estate in Lukavec.

In 1760 Haydn married – one of the biggest mistakes of his life. He’d been in love with one of his pupils in Vienna. When she became a nun, he married her sister. She had no love of music, no appreciation of her husband’s greatness and even used his manuscripts as hair-curlers. He was separated from her for most of his life but still sent her money. It’s said that, though he corresponded with her, he never opened her letters.

The turning-point in his life came in 1761 when Prince Anton Esterházy, who’d heard one of Haydn’s symphonies at Lukavec, invited him to become second Kapellmeister at his estate in Eisenstadt. Though the Prince died the following year, he was succeeded by his brother Nicholas – the fanatical music-loving ‘Nicholas the Magnificent’ who entertained on a truly lavish scale and built one of the most splendid castles in Europe, comprising a 400-seat theatre.

Here Haydn remained until 1790 and it was here that he composed most of his 83 string quartets, 80 of his 104 symphonies, nearly all his operas as well as keyboard works – let alone a huge amount of music written for the Prince to play himself. Every week, Haydn and his orchestra had to present two operas and two concerts plus daily chamber music for the Prince. His salary was generous and Haydn was encouraged to compose as he wished. As he himself wrote: ‘I was cut off from the world, there was no one to confuse or torment me, and so I was forced to become original.’ The members of the orchestra loved him (hence his nickname ‘Papa Haydn’) and Haydn even got on well with the Prince – it must have seemed like a dream.

By 1781 Haydn was acknowledged throughout Europe as a genius, honoured by all. He made only brief annual visits to his beloved Vienna but on one of them he met Mozart for the first time. Mozart was 25, nearly a quarter of a century younger than Haydn. The two became close friends, for Mozart admired Haydn’s music (his first six Viennese string quartets are dedicated to him) while the ever-generous Haydn described Mozart as ‘the greatest composer known to me either in person or by name’ and set about promoting Mozart’s works rather than his own. The two learnt much from each other.

Prince Nicholas died in 1790 and was succeeded by his son Paul Anton, who was more interested in paintings than music. Still, an annuity of 1000 florins kept Haydn as the nominal Kapellmeister to the Esterházys, allowing him to live permanently in Vienna. The same year, the enterprising impresario Johann Peter Salomon invited Haydn to London for a series of concerts. The composer was feted wherever he went and returned to Vienna 18 months later with a small fortune.

Haydn returned to London for further triumphs in 1794 and later in the year returned to Eszterháza. Paul Anton had died, succeeded by his son (another Prince Nicholas) who planned to revive the Haydn orchestra. As Kapellmeister, Haydn now turned his attention to choral works. From this period come the six late Masses, The Creation and The Seasons.

In his mid-sixties, Haydn’s health began to fail and he resigned as Kapellmeister in 1802, though Prince Nicholas II increased his pension to 2300 florins and paid all his medical bills so that Haydn should suffer no financial burden. Haydn made his last public appearance in 1808 at a concert given in his honour conducted by Salieri.

In 1809 Vienna capitulated to Napoleon who ordered a guard of honour to be placed round Haydn’s house. When Haydn died, the music at his memorial service was the Requiem by his favourite composer, Mozart.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.