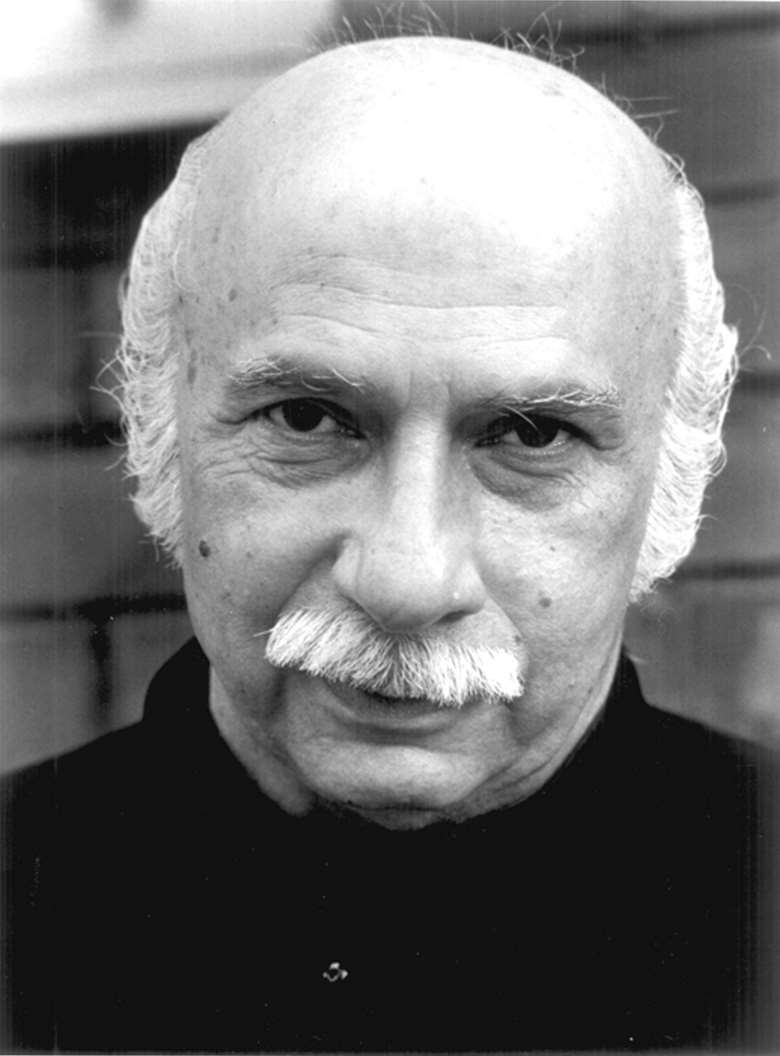

Obituary: Giya Kancheli

Ivan Moody

Wednesday, October 2, 2019

The Georgian composer has died aged 84

With the death of Giya Kancheli at the age of 84, the world has lost a musical colossus. His music, which on the surface became ever more austere, was in fact always a semi-dormant volcano, liable to erupt unexpectedly at any moment with shattering power.

Born in Tbilisi, Georgia, in 1935, Kancheli studied composition at the Conservatoire of his native city with Iona Tuskiya between 1959 and 1963. His reputation in Georgia is immense, and he became known to vast audiences on account of his work in film (he wrote music for more than 40) and theatre, becoming musical director of the renowned Rustaveli Theatre in 1971. At the same time, he wrote a remarkable series of symphonies, the seventh and last of which, entitled Epilogue, was written in 1986. The first work of his I heard, at a time when it was all but impossible to find his music in the West, was Svetlaya pechal (‘Light Sorrow’, 1988), which appeared on a recording from the Leningrad Festival. It was written in memory of the children killed in World War II, and made a singular impression on John Cage, who described it as ‘the absence of technology’.

In 1991, as the Soviet Union broke up, Kancheli moved to Berlin, and then in 1995 to Antwerp, where he became Composer-in-Residence to the Royal Flemish Philharmonic Orchestra, but his exposure in the West had already begun to gain traction in 1992, when his epic Liturgy: Vom Vinde Beweint for solo viola and orchestra appeared on ECM Records, heralding a magnificent series of recordings of his post-Soviet work. The soloist, Kim Kashkashian, and the Orchester der Beethovenhalle Bonn were conducted by Dennis Russell Davies, who became a fervent advocate of the composer’s music. Kancheli also enjoyed the advocacy of such musicians as Yuri Bashmet, Gidon Kremer, Kurt Masur, Mstislav Rostropovich and the Kronos Quartet.

For Bashmet he wrote Styx (1999), for solo viola, choir and orchestra, a memorial to fellow composers Avet Terteryan and Alfred Schnittke. Its pervasive sense of farewell is characteristic of most of Kancheli’s music; Abii ne viderem (1992-94), which means ‘I turned away so as not to see’, is effectively a farewell to Georgia, then riven by civil war. Titles such as Lament (violin, soprano and orchestra, 1994) along with And Farewell Goes Out Sighing (violin, countertenor and orchestra, 1999) reinforce this impression, but the music itself, while confronting with brutal honesty themes such as loss, pain and homesickness, transcends any sense of mawkishness in its sheer sonic beauty.

Kancheli was unfailingly charming as a person; I had the good fortune to meet him several times over the years, both in London (at the Almeida Festival, in 1990, where he was genuinely delighted that I had written the first published article in English on his music) and in Lisbon. As he lit cigarette after cigarette, we discussed his work and his motivation in as much depth as we could (given that we were veering between Russian and German), and it was clear to me that I was in the presence of a man of singular, unwavering purpose. At the premiere of his searingly beautiful Diplipito (1997), written for the countertenor Derek Lee Ragin, an eminent Spanish composer sitting next to me complained that Kancheli had not done anything with his musical material. But he’d missed the point: the granitic force of that material was itself the essence of Kancheli’s unique vision, and its own justification.

Giya Kancheli: born Tbilisi, August 10, 1935; died Tbilisi, October 2, 2019