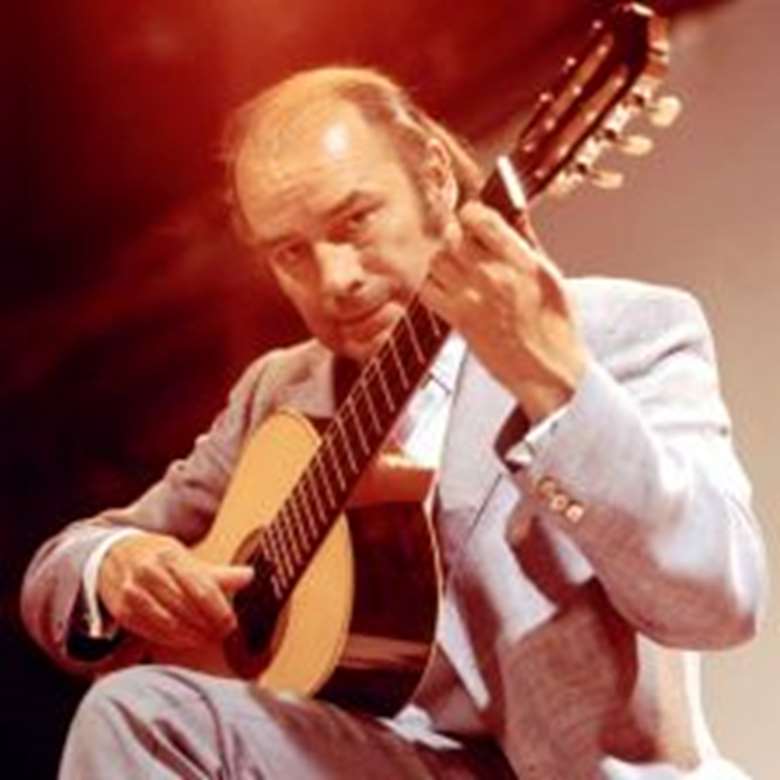

The guitarist Julian Bream has died

Friday, August 14, 2020

Born July 15, 1933; died August 14, 2020

The guitarist Julian Bream has died at the age of 87. In 2013, Gramophone presented him with a Lifetime Achievement Award, and here we reprint an edited version of Martin Cullingford's tribute.

The recipient of Gramophone’s Lifetime Achievement Award should have achieved more than success and longevity. Many achieve that, but few receive the accolade. The recipient should, through a lifetime devoted to performing, pursuing and understanding their art at the highest and deepest possible level, have enriched the cultural world of their day, served their instrument and its repertoire with tireless advocacy, and left a legacy that will inspire players and listeners for generations to come. All this can easily be said of our Lifetime Achievement Award-winner, the guitarist Julian Bream.

When the young boy from south London began playing, the guitar still sat on the sidelines of the classical music world; when he took his place at the Royal College of Music in 1949, aged 15, he had to enter as a pianist. The advocacy of Andrés Segovia had got the instrument so far – on to the main concert stage for a start. But Bream was to pick up Segovia’s mantle, and not only champion the instrument as a performer but, through inspiring and persuading composers to write for it, help give the guitar a modern repertoire to stand proudly alongside that written for any other solo instrument. Prior to the 20th century, the guitar’s composers were – well, guitar composers largely. The great composers of the classical canon had not written for it. Now some of the leading composers of the day – including Britten, Tippett and Henze – were doing just that and, furthermore, many were from Britain or countries far removed from the passion and rhythms of the Spanish soul in which the instrument is rooted.

‘I just knew I had to play the guitar,’ says Bream. ‘I found I could speak through the guitar. Because you have the feel of the strings with both hands and it’s up against your solar plexus, it’s real, and so there’s nothing between you and the music.’ Direct communication, physicality, honesty: those familiar with Bream’s discography, begun back in 1955 and distinguished by an instinctive musicality rich in tonal colour, will nod in recognition. ‘Colour was always a part of playing,’ he says, something ‘initiated by hearing Segovia play – but I went a few stages beyond. I became enticed by the whole style of colour.’

Initially encouraged by his first record label to record Dowland, Bream came to develop a love for the lute, founding the Julian Bream Consort and building bonds with singers including Peter Pears. ‘I know that a lot of people were suspicious of my pedigree on the lute and its music. But I was quite happy to be suspect. Because I loved playing the instrument so much my way, to be honest I didn’t really give a damn about anyone else, I knew that I was doing it for myself. And the interesting thing is that when you do things for yourself you stand a good chance of making other people happy.’

Bream gave up playing a decade ago and devotes much time now to his Trust, founded to support young players and to commission new works. ‘I wanted to create a literature, a music which is of now, of our time – for young people who are young now but who in their maturity will have a literature which speaks to them.’

When we met in the summer, at his home deep in the idyllic peace of the Wiltshire countryside, Bream was excited about a recently received work commissioned from Sir Harrison Birtwistle, describing it as ‘very original. I think he’s written a very good piece. It has a lot of unusual sounds and textures – he’s really going into the possibility of finding original sounds in the instrument.’

The other transformation over the past decade, Bream feels, is that he’s ‘changed from a player into a listener. The older you get, the more things you find out, that you concentrate on. Something entices you – a phrase, a little rhythmic whatever – and you hear it repeated, an echo of something. I listen in a more acute way now.’ He assures me there’s no frustration that the years of virtuosity are now behind him; one believes him, so reflectively does he talk of his new life as a listener, though he does add with a smile, ‘The only thing is, I would have liked to have gone through and played this piece by Birtwistle.’

‘Music has been a wonderful education for me,’ he concludes. ‘It has enriched my life immensely and it goes on doing that. It is a way of life really.’

Listen to Julian Bream in conversation with Martin Cullingford as part of our Gramophone Milsetone EFG Podcast series