The British composer, Sir Harrison Birtwistle has died

Monday, April 18, 2022

Born July 15, 1934; died April 18, 2022

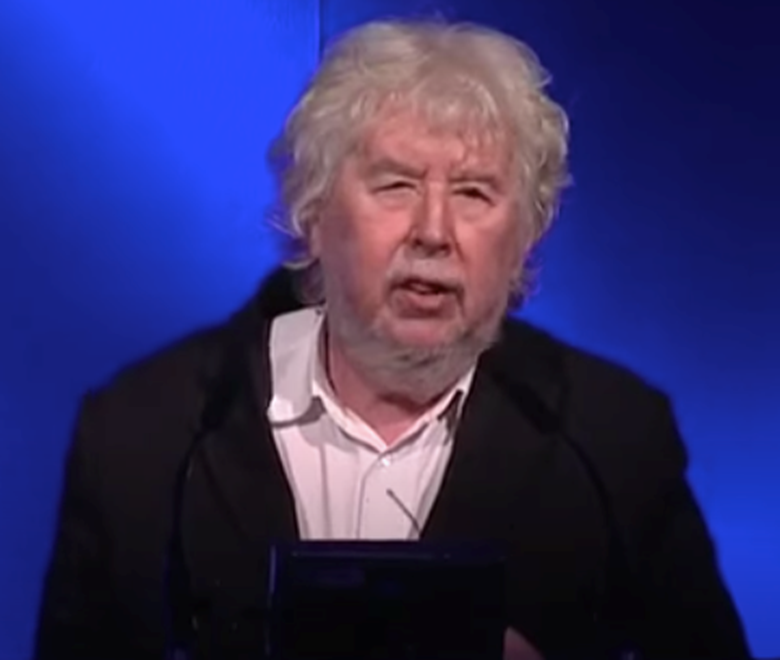

We learn with sadness of the death, aged 87, of one of the UK's greatest composers. To commemorate this major musical figure, we revisit an article by Arnold Whittall, published in October 2013, to celebrate his 80th birthday, and preface it with Sir Harrison's acceptance speech from the 2011 Gramophone Awards when he won the Contemporary Award for 'Night's Black Bird' (NMC).

With the revival of The Minotaur at Covent Garden, a new production of Gawain at the Salzburg Festival and a major premiere at the Aldeburgh Festival – all of which took place this year – plus a series of concerts (‘Birtwistle at 80’) planned for the Barbican in London in May 2014, the gradual transformation of Sir Harrison Birtwistle from youthful iconoclast to venerable Establishment figure seems complete. Not even the furore occasioned by the programming of his abrasive Panic for alto saxophone, drummer and orchestra without strings at the Last Night of the Proms in 1995 could derail that transformation. But the Establishment status that goes with a knighthood, a university professorship and a stint as music director at the (then new) National Theatre does not mean that Birtwistle’s music is less challenging now than it was when he first came on the scene more than 50 years ago.

Not until the breakthrough year of 1986 was Birtwistle’s position at the centre of British musical life beyond dispute. Before then, the pre-eminence of Britten, Tippett and younger composers such as Peter Maxwell Davies and John Tavener left him nearer the margins than the centre, despite the impact within the contemporary music world of such boldly sculpted works as Tragoedia (1965) and the opera Punch and Judy, first heard at Aldeburgh in 1968 to the unalloyed distaste of Benjamin Britten. But in 1986 the premieres of two further operas, The Mask of Orpheus and Yan Tan Tethera, and the first performance of the monumental orchestral work Earth Dances forced him to the front, with the recognition that for all his supranational radicalism his music had deep roots in a profound if uneasy sense of Englishness.

Although complemented by a fascination with ancient Greek myths in general and the Orpheus legend in particular, that uneasy Englishness reached fulfilment when Birtwistle found ways of aligning his un-emollient brand of expressionism with the vocal and instrumental music of John Dowland. At first, this alignment was only glancingly evident in the orchestral compositions The Shadow of Night (2001) and Night’s Black Bird (2004). But in 2009 the Aldeburgh Festival mounted Semper Dowland, semper dolens: Theatre of Melancholy, in which a sequence of six Dowland songs, the lute accompaniments recast for instrumental ensemble, alternated with seven transformed versions of the Lachrimae pavans. After the interval came The Corridor, a scena for soprano, tenor and six instruments, to a text by David Harsent. Here the archetypal separation of Orpheus from Eurydice is portrayed as a deeply melancholic ritual in Birtwistle’s own most subtly intense post-Dowland manner. This two-part ‘theatre of melancholy’ powerfully reinforced Birtwistle’s commitment to well-contrasted forms of music drama, in which the operatic and the lyrical interact with instrumental processionals.

Between the early 1960s and the mid-1980s many of Birtwistle’s best and most ambitious pieces – Verses for Ensembles (1969), Meridian (1971), Silbury Air (1977) and Secret Theatre (1984) – were written for the London Sinfonietta, but he was also working on the larger canvases of orchestral and concerto-like compositions, none more imposing than the Dürer-inspired Melencolia I (1976) for clarinet, harp and strings. There was also a wryly oblique tribute to his northern roots in Grimethorpe Aria (1973) for brass band. But the inspiration behind (what eventually became) The Mask of Orpheus (begun in 1973) led to various vocal works involving classical themes – The Fields of Sorrow (1971-72) stands out – and orchestral or ensemble pieces that embodied pictorial rather than purely abstract thinking: An Imaginary Landscape (1971), The Triumph of Time (1972) and Theseus Game (2002).

As a vocal composer, Birtwistle has combined a commitment to opera (after Gawain – The Second Mrs Kong, The Last Supper and The Minotaur) with a taste for concentrated, allusive poetry (Christopher Logue, Rainer Maria Rilke, Paul Celan). Since returning to the UK from France during the 1990s, he has not retraced his steps to live in Lancashire (he was born in Accrington and studied initially in Manchester); but one important recent composition, the string quartet The Tree of Strings, relates to a period (in the 1970s) spent living on the Scottish island of Raasay. Today he might have fewer hang-ups than formerly about using traditional generic titles (his Concerto for Violin and Orchestra was premiered in 2011), but this has nothing to do with a retreat from radicalism; rather it reflects his determination to avoid the hackneyed and the predictable. Like all the most constructive members of the great generation of musical modernists, Birtwistle takes the traditional – the elemental – and reinvents it. Although he’s now part of the Establishment, he is there to challenge, not to conform.

Arnold Whittall (Gramophone, October 2013)