The Choir of King's College London: capital assets

Matthew Power

Friday, December 2, 2022

Though King's College London is not even 200 years old, its list of alumni reads like a Who's Who of the great and the good from all walks of life. Gaining a reputation of distinction in the present era is its choir, directed by Joseph Fort, who are building on a productive contract with Delphian Records

ANDY LANE

Walking south from London's theatre district, I head through a growing cacophony of building works – scaffolding, drilling, digging, road surfacing, kerb laying. But this isn't a mere facelift, it is a major urban landscaping to pedestrianise Aldwych and the Strand, banishing the rumble and squeal of buses and taxis, and sculpting gardens, terraces and cycle paths among the shops, cafés and churches. With the principal phase almost complete, an ongoing review of the public use of and reaction to the space over the next three years will lead to a permanent completion in 2025.

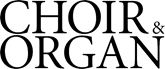

The historic campus of King's College London (KCL) sits at the heart of this burgeoning piazza. The terrace of ground-floor windows on the Strand itself is filled with portraits of famous King's alumni, a dazzling list which includes nurse and social reformer Florence Nightingale, novelist and poet Thomas Hardy and Nobel Peace Prize winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu. I am visiting during Freshers' Week and hundreds of excited 18-year-olds, who will soon add to this roll call of achievement, are dashing around trying to work out where to go. There is an incredible buzz. One of the two founding colleges of the University of London in 1829, KCL has awarded its own degrees since 2008. It boasts more than 33,000 students spread across five locations; the original Strand campus (now incorporating Bush House and buildings on Kingsway) hides within it the Grade I listed chapel redesigned in 1864 by Sir George Gilbert Scott.

Dr Joseph Fort is in his eighth year as college organist, director of the chapel choir and lecturer in Music. The choir was established, before Music became an academic option here, in the mid 19th century by William Henry Monk, familiar to many church musicians as a hymn writer. How has it developed since his time?

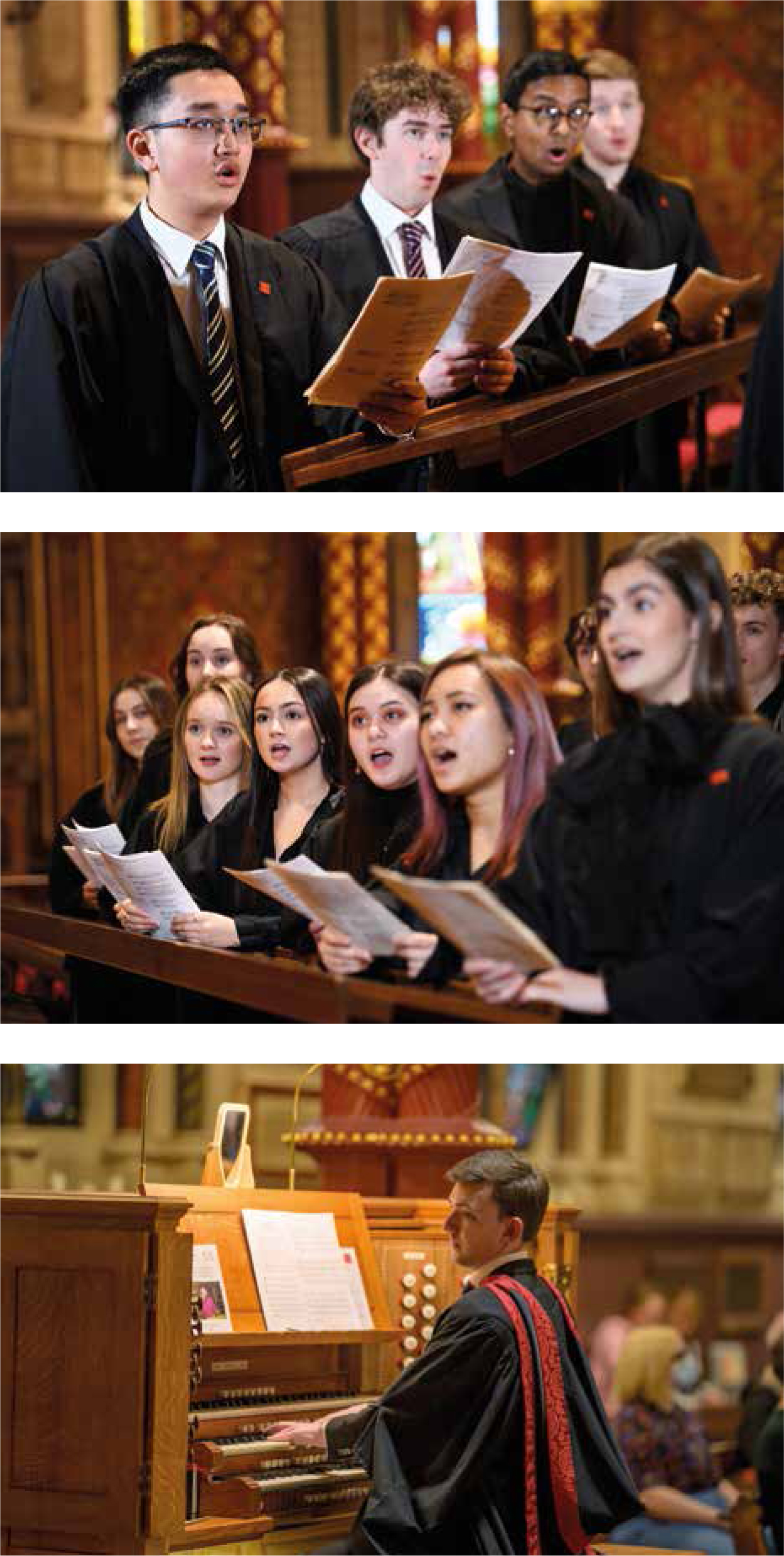

‘The archive shows that W.H. Monk was employed by the Theology department to train singers,’ Fort explains. ‘The college had a barrel organ, then in 1866 “Father” Willis built an instrument.’ In 1932 the chapel's vaulted ceiling was lowered when the Anatomy department was constructed above; the organ and its console were repositioned and tonal modifications made by Henry Willis III. Fort's immediate predecessors here were both long-serving and highly respected: E.H. ‘Ernie’ Warrell directed the music for 45 years until 1991 and was for some time also organist of Southwark Cathedral; he was followed by David Trendell, who served for 23 years until his death in 2014.

Choral scholars sing two services a week during term time; former organ scholar Mitchell Farquharson at the Willis/Mander organ © ANDY LANE; ANDY LANE; DAVID TETT

After some neglect of the organ, Bishop & Son made minor repairs in the early 2000s but it became clear that a major refurbishment was required. David Trendell garnered proposals and this bundle of reports was handed to Fort when he took up his post. Mander Organs were selected to rebuild the instrument, with David Titterington as consultant; the instrument was completed in 2018. Half of the present pipework is from the original Willis organ and the rest is new, as is the handsome movable three-manual console. The organ case has been brought forward into the chapel for better egress. The choir sings from stalls close to the organ so ensemble is easily achieved. As we talk about the layout, Fort points at random cupboards and walls in his office, which fills redundant gallery space running the length of the chapel. There is ample room for a Bechstein grand piano at one end, and the choir's complete music library at the other.

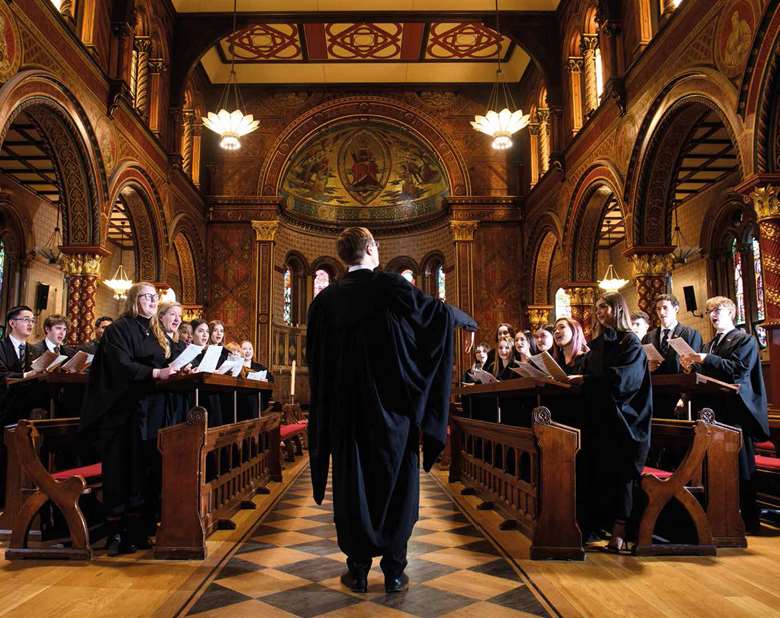

The choir comprises 28 choral scholars. During term time they sing twice weekly: Choral Evensong on Tuesdays, and Eucharist on Wednesday lunchtimes, there being little activity in the west end on Sundays and no residential campus. What is the choral scholar experience like?

‘The main benefit, of course, is singing in the choir,’ says Fort. ‘Most are undergraduates and will hold their scholarship for three years. A half to two-thirds are studying Music. They receive [at least] seven hours of singing lessons per annum with teacher Bertie [Robert] Rice, plus an annual £700 stipend.’ A mix of academic disciplines among the singers creates camaraderie; sometimes in an all-music environment like the ‘hot house’ experience of conservatoire, claustrophobia can develop. Here there is none of that. ‘We had one singer who was studying Nursing; she always had the best excuses for arriving late, like “someone was sick in my shoes”! There's a supportive and friendly atmosphere in the choir that seems to perpetuate from year to year. Friendships formed here do often seem to be lifelong ones.’

There is a single organ scholar, usually appointed for one year, receiving a stipend of £4,000 in return for playing at services. However, organ scholars do not have to be students at KCL and may sometimes be studying at a conservatoire; this gives them the advantage of gaining liturgical experience at KCL alongside solo repertoire tuition at their college. One such example is James Orford – organ scholar at KCL while studying at the Royal Academy of Music (RAM) prior to obtaining the organ scholarship at St Paul's Cathedral. He went on to become organist-in-residence at Westminster Cathedral and is now a familiar performer and recording artist.

With an annual intake of new singers and departure of established voices, does the choir's sound constantly evolve or is there a sense of Michaelmas term being a familiarisation process for new scholars? ‘The sound does evolve; there are key things I do from year to year. Certainly, the recording we made in 2017 sounds quite different to what we released last year, and I think it should be like that. In that first term we do [familiar repertoire] so that I can spend time on diction, for instance. It's a matter of persuasion with choirs – actually to get a D to sound properly.’ Fort soon became notorious among the choir for his obsession with articulated Ds: ‘They gave me this…’ he pulls out a sponge bag emblazoned with a large letter D!

Sheena Jibowu is an alto choral scholar in her second year reading Music. ‘The most enjoyable part of being a choral scholar at King's has to be the exposure to everything from Renaissance polyphony to 21st-century pieces,’ she says. ‘The most challenging part is the number of rehearsals, and trying not to compare yourself to the amazing singers here.’

Tom Lane is a third-year bass reading English. How does that complement a choral scholarship? ‘There's an overlap, of sorts, between a literature degree and a music degree – you need to be an intense listener as well as an avid interpreter to succeed in your subject.’ He gains huge satisfaction from the choir's commitment to perfecting its repertoire: ‘I wasn't always taken with Rachmaninov's Vespers, but the hard work made me love it. And it is a credit to Joe that this culture of ours, of a serious and blossoming intent, should be as rewarding as it is demanding.’ Despite its central location and services planned around the working week, worshippers at Evensong and Eucharist can sometimes be sparse. ‘I would implore anyone passing our way, on Tuesday evening or Wednesday lunchtime, to drop in – you may have us all to yourselves!’

Alongside KCL's academic profile as the go-to place for musical theory and analysis, nearly 90 per cent of undergraduate musicians here study an instrument or voice with a tutor from the RAM. Fort explains how students' experiences can be tailored to their musical strengths: ‘When Thurston Dart established the Music faculty back in 1964, his guiding principle was that performance should be combined with musicology in a way that it wasn't in other universities. There is an emphasis on performance informing the musicology that we teach.’ Catering to the needs of students is crucial and Fort cites the in-vogue degree course ‘pathways’ that enable this: ‘If a viola player from the National Youth Orchestra arrives, and wants to continue doing four hours’ practice a day as well as an academic degree, then we would make sure they were supported to do so with an advanced performance module.’

Plans for 2023 include outreach. ‘It is frightening how many primary schools literally have no musical resources,’ Fort worries. ‘Using Tallis's Spem in alium as inspiration, and working with the National Poetry Society, a poet and a composer will explore with the children their ideas of what “hope” might be. We will create a text that encodes those ideas. The composer will then write a piece that the KCL choir can sing but which will also have an excisable chunk that can function as a new song for that school.’ Fort will then ‘give the piece back to the school’, returning with the composer and a choral scholar from KCL, and teach the pupils to sing it. ‘It may not work in every school, but we hope to create some culture of singing where it doesn't currently exist.’

A workflow of musicological study forged through performance and recordings makes for a vibrant environment in which to host the New Music partnership between C&O and the Choir of King's College London during 2023. What kind of mentoring does Fort aim to offer to our choral and organ composers? ‘Some guidance in selecting texts that might work [best] musically and for which there might be demand. With the New Music series, it's not just a focus on our [premieres] of these pieces but about getting them [performed in] the wider world. The second thing is helping those who have done less choral writing… Things to consider when writing for choir that you would never think of when writing for instruments… How harmony moves, thinking from a singer's mindset: how you voice a chord. We can consider the nuts and bolts of how best to do that.’

KCL director of music Dr Joseph Fort: ‘It's a matter of persuasion with choirs’ © KAUPO KIKKAS

Organ writing is a unique challenge, even for organists. Sharing the potential of the instrument is fundamental, Fort believes. ‘Romantic instruments, like the chapel organ, have so much scope for orchestral colour. You can tell when a piece has been written by an organist – Stanford, for example – because the music is just waiting for you to apply the colour. Another consideration is registration; making sure that there is always time for a player to do that.’

Our New Music partnership with the Choir of King's College London will be enhanced by sponsorship from PRS [Performing Right Society] for Music, giving our six young composers additional support. As in previous years, C&O will commission four choral pieces and two organ works during 2023, and the scores will be available to download and print, free of charge, for six months before copyright reverts to the composer. This year we plan to make video recordings of all six pieces available online, and for some of the premiere performances to be given around the UK as well as at KCL. We hope that choral directors and organists will join us on our musical journey to explore and perform new works from the next generation of gifted composers. And when you do, we'd love to hear about your experiences!