Peter Phillips and The Tallis Scholars: another country

Clare Stevens

Thursday, March 2, 2023

‘The past is another country’ - and so was early music when the Tallis Scholars first assembled to perform it 50 years ago. Founder-director Peter Phillips talks to Clare Stevens about how performing techniques have been honed in the intervening decades, and how Renaissance music has enjoyed its own rebirth

PHOTOS COURTESY THE TALLIS SCHOLARS

When Peter Phillips was a student at Oxford in 1972 he heard his tutor, David Wulfstan, conduct The Clerkes of Oxenford in a performance of Thomas Talliss Gaude Gloriosa in Magdalen Chapel, and fell in love with Renaissance polyphony, as sung by that pioneering consort. Ever since, he has been happily engaged in the task of trying to recreate the sound he heard that night with his own group of singers.

This year they celebrate the 50th anniversary of their first concert, on 3 November 1973. Ten people, conducted by Phillips, sang a programme of music by Obrecht, Ockeghem, Lassus and Victoria, which he admits was overly ambitious and over-rehearsed - yet never with the full complement of singers - to a tiny audience in St Mary Magdalen Church, Oxford. They didn't even have a name. ‘Our amateurishness was absolute,’ he recalls in his 2003 book about the ensemble, What we really do. But they were ambitious enough to tackle Talliss 40-part motet Spem in alium, then rarely heard, in their second concert just a month after the first.

It was not until 1976 that they gave their first concert outside Oxford, in the chapel of their conductor's old school, Winchester College. It was also their first concert under the name that was to become famous: The Tallis Scholars.

The line-up has changed, of course, in the intervening five decades. Phillips explains how in the early years it was particularly fluid as he navigated the transition from amateur to professional ensemble, facing challenges such as the refusal of the singers’ union Equity to allow him to employ professional and amateur singers together: ‘I pleaded, as John Eliot Gardiner and others had also done, that my group depended on certain essential members who in those days were just as likely to be amateur as professional, since the professional circuit provided relatively few voices which were able to sing polyphony in the way I wanted it sung … In the end a compromise was reached by which I could ask anyone to sing provided I paid them all the same.'

Listen to the Scholars’ first commercial recording of Allegri's Miserere, released by EMI in 1980, and their 2005 version on their own Gimell label, and the biggest difference you can hear is in the singers’ vocal technique. The original group gave very accurate performances and diligently followed Phillips's direction, but not all of them had the flexibility to do so subtly, compared to their fully professional counterparts.

‘The singing world that surrounded us in 1973 was so different,’ reflects Phillips. ‘We had very few choices and the choices we did have were students really, with little voices. Some of them did go on to stellar solo careers, but the downside of that is we couldn't hang on to them for long.’ Mark Padmore, for example, is listed among the singers who appear on The Essential Tallis Scholars box set released in 2003, as is Jeremy White, still a principal bass at the Royal Opera House in his late 60s. Others decided they preferred the security of careers outside music.

Obstacles also included perceived hostility from producers at the BBC, which meant Phillips had no radio showcase for the Scholars. To the extent that anyone in the UK was aware of Renaissance choral music, they wanted to hear it performed by robed collegiate and cathedral choirs of men and boys, and it seemed impossible for an unknown ensemble to establish itself.

However, they did gradually begin to receive invitations to perform at festivals in Europe, the UK and the US. A significant breakthrough came with what Phillips has called ‘a near-miraculous’ invitation from concert promoters Musica Viva to tour Australia in 1985. It was made over two years in advance and obliged them to keep going; without it, he believes they would have foundered. The tour was a steep learning curve, but established a template for the future.

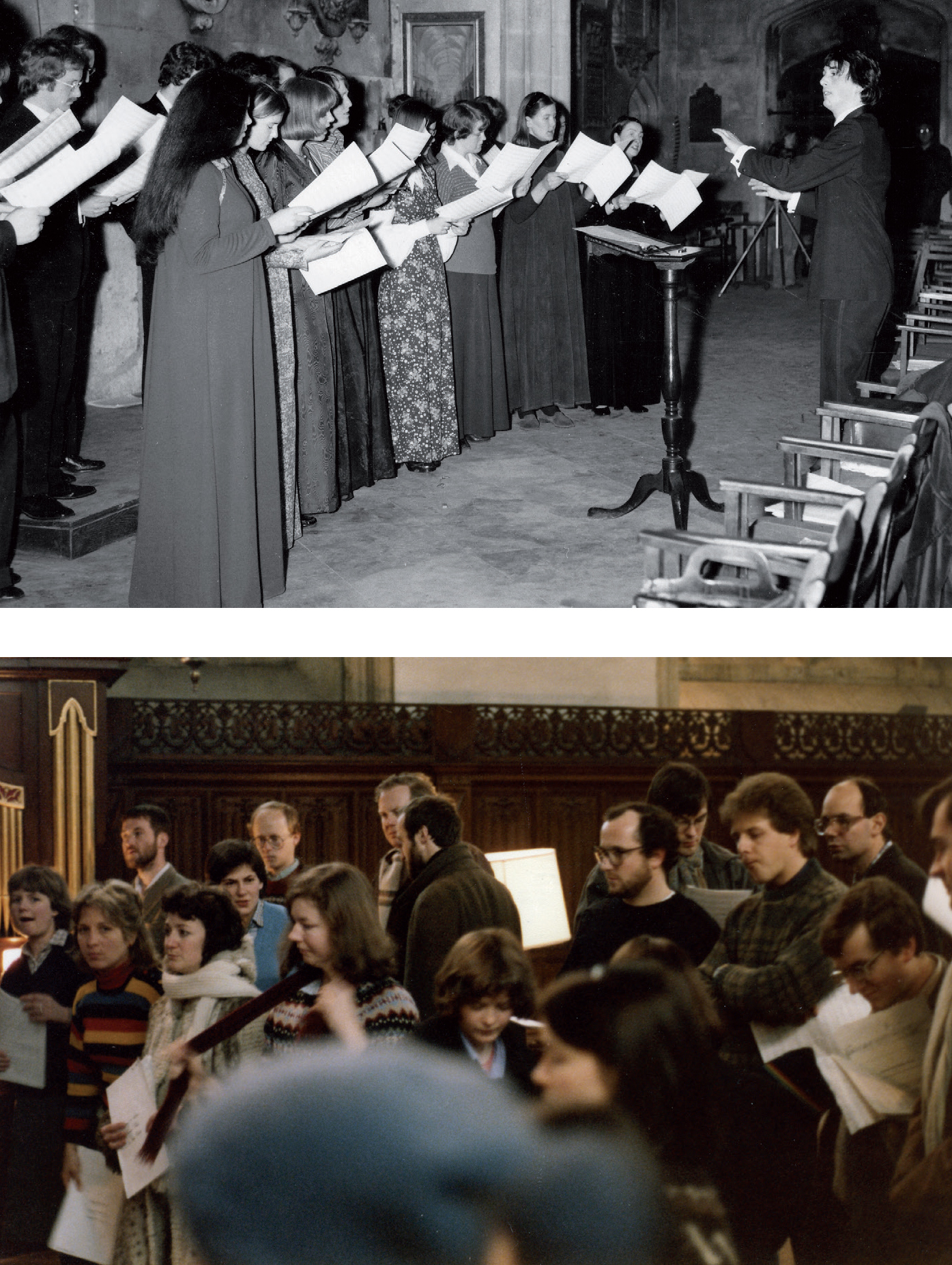

The Tallis Scholars in 1977, and Performing Spem in alium in 1984

Recordings on their own label also helped to introduce them to audiences and build their reputation, despite the slow gestation process for each new release due to their directors’ love of detailed editing. Gimell was founded by Phillips and producer Steve C. Smith in 1980, solely to make and market recordings by The Tallis Scholars. Single-artist labels are now commonplace, but Gimell was a pioneer, anticipating the trend and giving Smith and Phillips a head start both in the technique of recording a cappella singing - initially usually in the magical acoustics of Merton College Chapel, Oxford, but later, to reduce external noise, in Salle Church, Norfolk - and in the experience of marketing a single repertoire and one artist.

Their first famous Allegri Miserere disc, complementing the work that is still their calling card around the world with Mundy's Vox Patris caelestis and Palestrina's Missa Papae Marcelli, reached number one in the UK HMV Classical Chart. Smith was able to take back the licence to the recordings from EMI after five years, and its continuing success supported Gimell's future releases. The Scholars were also early adopters of the compact disc format, placing the first commercial order with a UK manufacturer in 1984. Winning the Gramophone Record of the Year Award in 1987, the first independent label to do so, for Josquin's Missa Pange lingua and Missa La solfa re mi, set the seal on their success. Gimell has now produced more than 60 recordings ofthe ensemble.

By the time counter-tenor Patrick Craig was recruited in 1996, the team of professional singers was ‘on a serious roll’ of recordings and concerts. ‘For me it was an incredible line-up to slot into,’ he recalls. ‘You had Sally Dunkley and Francis Steele at either end, Deborah Roberts doing the high notes, Tessa Bonner and then Caroline Trevor next to me; and Philip Cave was a big influence, on the tenor part.’ Craig was two years out of music college, and combined the job with singing as a vicar choral at St Paul's Cathedral; the two roles usually dovetailed fairly well. Tenor Stephen Harrild and soprano Janet Coxwell joined the Scholars at around the same time. ‘I learned how to sing that repertoire from those people.'

Craig explains that the essence of Phillips's approach to singing Renaissance polyphony is setting a tempo and allowing the singers to interpret the lines, drawing on the musicological expertise of colleagues such as Dunkley and Steele and absorbing the style by osmosis.

‘For instance, for me, [an important aspect of the performance style is] the quaver movement,’ he says. ‘The short notes in Renaissance music need to go backwards, they need to go out of the back of your head, and they need to go slowly. We don't sing it like Baroque music, we don't rush the short notes, we don't throw away the dots. That makes the Scholars’ interpretation of Renaissance music very special and very solid. It's not talked about a lot in rehearsal, you just pick it up; rehearsals were minimal and still are.'

Phillips acknowledges that he doesn't enjoy the rehearsal process; he likes editing recordings, but most of all he loves giving concerts. ‘Right at that very first concert I had an ideal sound in my head, which I pieced together from what was going on in Oxford around me and from listening to discs made by the Cambridge colleges. I've preserved that sound as an ideal of beauty in my head; it's never been compromised and it has never changed. When I don't get it I'm very aware of that fact, but I just shrug my shoulders and make the most of what I've got on the stage in front of me on that occasion. As the years have gone on it has become more and more likely that I'm going to get it.'

That is partly because the proliferation of choral groups specialising in early music and the much greater general awareness of historical context, not to mention the Scholars’ own back catalogue of recordings, mean that his singers now understand what they are aiming for. Recent generations have benefited from much better training in vocal technique and, in particular, Phillips cites the introduction of choristerships for girls in cathedral and collegiate choirs, which means that young sopranos and female altos now have the same level of musicianship and performing experience as their male counterparts.

Soprano Emma Walshe is one such, having been a member of Gloucester Cathedral Youth Choir and the National Youth Choir of Great Britain as a teenager and then a choral scholar at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge. She also benefited from an apprenticeship with the Monteverdi Choir and early experience with The Sixteen, and now sings with a variety of consort groups including the Gabrieli Consort and Tenebrae. Walshe made her debut with The Tallis Scholars in a 2010 recording for French TV and has been a regular member since 2014.

The repertoire of the different groups does not overlap as much as one might think, she says. ‘While I have sung some early repertoire with other groups, I wouldn't say it was their speciality, whereas with the Tallis Scholars it is. Particularly the Eton Choirbook music, Browne and that sort of thing - it's often quite tricky rhythmically, but we are just used to that style and it clicks in very quickly. We know how to get into the zone with it.'

Does she feel the conductors are all after a different sound … would the same group of singers sound different singing for Nigel Short, say, from when they are standing in front of Peter Phillips or Harry Christophers? ‘Absolutely. Peter likes quite a focused, direct sound, very rhythmically accurate. Not too much room in it, not too much rubato, not too much space, which works really well either for the early style or for minimalist modern music.’ (The Scholars do occasionally perform 20th- and 21st-century music by composers such as Tavener or Pärt.)

Concerts over the years have included a performance of Allegri's Miserere in the Sistine Chapel in 1994

The Tallis Scholars in their 40th anniversary concert at St Paul's Cathedral, London, in 2013

Phillips admits that the sound does not change much according to repertoire. ‘We're an instrument, like an organ, or a harpsichord, or any keyboard instrument, with a sound which we apply to different repertoires.’ He is confident that, within the limitations of varying church and concert hall acoustics, the audiences who throng to Tallis Scholars performances around the world will hear what they are expecting to hear through familiarity with the ensemble's recordings and YouTube videos.

In fact, he adds, trust in the ‘product’ is now so secure that he can programme almost anything, by composers their audiences have never heard of, and as long as it is performed in that recognisable style, it will be well received: ‘I'm given licence to explore, for example with the recent Josquin des Prez 500th anniversary. We've had a fantastic time over the past two years, singing music no one's ever heard before, in sold-out concerts, including last July when we sang all 18 of his Masses over four days at the Boulez Saal in Berlin, in a series that was very well conceived by the promoters.’ The Josquin project also included the release in November 2020 of the last of nine albums of the Masses, in a recording that won both BBC Musics Recording of the Year and Gramophone's Early Music Award for 2021.

As the Scholars’ own 50th anniversary year begins, Phillips has lost none of his zest for performing, which Patrick Craig says is an essential ingredient in the group's success. ‘There's nothing he'd rather do than be on tour doing a Tallis Scholars gig, and he has incredible stamina, he's never ill; I think he has missed something like half a concert out of 3,000, so you know that come what may, if you're singing with the Scholars or you've booked a ticket to hear them, it will always be Peter conducting. His energy, his “let's do this” attitude and his relentless affection for the product are very infectious.'

Plans for the year include premiering a large-scale Mass by Ludwig Daser, a little-known contemporary of Lassus. ‘His music looks absolutely fascinating on the page,’ says Phillips, ‘and I'm interested in him because he was doing perfectly well in Munich, everybody loved him, then Lassus came along and Daser was eliminated from the historical record. We will put Lassus in the other half of our programme so that people have something familiar to hang on to, and I think the relationship between them will tell a neat story.

‘We're also going to make an hour-long documentary, for which I've raised the finance, about what the Scholars do and how we rehearse. We've found a piece by John Browne in the Eton Choirbook that has never been performed and we're going to be filmed in Eton College Chapel rehearsing it, so the documentary will include the premiere of part of it. And on 3 November we're going to have a big anniversary party in Middle Temple Hall in the City of London … not really a concert, though there will be short performances, but a chance for our core audience to meet and talk to us.’