Gather around: the art of singing from a common choirbook on a lecturn

Magnus Williamson

Sunday, April 2, 2023

Magnus Williamson discusses the Tudor practice of singing from a common choirbook on a lectern, which leads to an ‘ear-opening experience’

BAYERISCHE STAATSBIBLIOTHEK, MUNICH, MUS. MS. A II 1, P 186

Orlandus Lassus directs the Bavarian court Kapelle. The red cloth draped over the choirbook lectern carries a quotation on etiquette from Ecclesiasticus 28:3: ‘Don't interrupt the music’

Singing Renaissance music raises many questions. Learned journals heave with disputations on performing pitch, on pronunciation, on tempi, temperament and so on. One crucial issue receives scant attention, though: the spatial dimension of being a singer in, say, Tudor England.

With William Byrd’s quatercentenary in mind, let us approach this question through his first workplace, Lincoln Cathedral, where he took up residence in 1563. Walking down its nave, like us he would have seen the medieval choir screen. Passing beneath it, he would have seen Treasurer John Welburne’s canopied stalls, already 200 years old in 1563 and still magnificent in 2023. Tiered rows of stalls flanked the north and south sides then as they do now, here as in other cathedrals; later on, we will expect the cathedral choir to process into these lateral stalls on Dec and Can, singing Evensong there in time-honoured fashion.

Antiphonal singing has been at the heart of western liturgy since the sixth century. The close association of antiphony with the old Latin liturgy riled Byrd’s puritan contemporaries. In their Admonition to the Parliament of 1572, the same year that Byrd quit Lincoln for the security of the Chapel Royal, John Field and Thomas Wilcox ridiculed the singing of traditionalist clerics who ‘toss the psalms in most places like tennis balls’. During his Lincoln years, Byrd would have been aware of the growing controversy around choral polyphony, with much of the debate swirling around the practice of Dec/Can antiphony. We can see how easily this spatial tradition could have been lost when we consider the absolute extinction of another time-hallowed singing style, once universal but now forgotten: singing at the lectern.

Arriving at Lincoln Cathedral in 1563, young Byrd may have noticed the absence from the central choir aisle of two pieces of historic pre-Reformation furniture. The choir rulers’ desk had once stood near the dean’s stall to the west. A combination of bench, bookstore, and conductors’ podium, this was the hub from which the rulers had micromanaged performances of the Latin Mass and Offices. Much further east had once stood the large brass or wooden choir lectern standing in medio chori. These pieces of furniture had once been essential to the performance of the old Latin liturgy. If the rulers’ desk was the control room, the choir lectern was the performative stage. Here, at the choir step, small groups of handpicked, silk-clad cantors had gathered to sing the most soloistic and elaborate chants, such as the verses of the Alleluia at Mass and the greater responsories at Matins, Lauds and Vespers. Unsurprisingly, these offensively exuberant chants were abolished in 1559, removing the main reason for having a large lectern, impeding the field of vision between choir stalls and presbytery.

In the 14th century, manuscript illuminators invariably included a lectern in depictions of polyphonic song

There was another rationale for the choir lectern: the singing of polyphonic music. As far back as the 1270s, Lincoln Cathedral’s customs had required those vicars choral and choristers with the best voices to sing polyphonic settings of Benedicamus, the final dismissal at Lauds and Vespers on feast days. This happened at the choir lectern at Lincoln and elsewhere.1 A few years later in 1289, a set of injunctions for St Paul’s Cathedral, London, also instructed that polyphony be sung at the choir lectern (rather than on the choir screen as previously). Indeed, the association between polyphony and lecterns became universal during the 14th century, when manuscript illuminators invariably included a lectern in depictions of polyphonic song. The surviving music manuscripts tell the same story: the commonest layout for polyphonic books in Britain before c.1530 is choirbook format, in which each voice-part is copied into a separate bloc on the opened pages of a single manuscript. All the singers read from the same book, not from individual scores.

The British experience reflected a wider European norm. Choirbooks were normative throughout western Europe until the Reformation, and in Counter-Reformation Europe for decades and centuries later (in Spain they continued to be copied in the 19th century and used into the 1930s). Brass or wooden lecterns were commissioned specifically for the singing of polyphony, for instance at the church of St Botolph, Boston (1520), some of which survive: the most famous is in King’s College Chapel, Cambridge. The Reformation changed this. With very few exceptions, Protestant Europe – including Britain – abandoned choirbooks.

© WIKIPEDIA

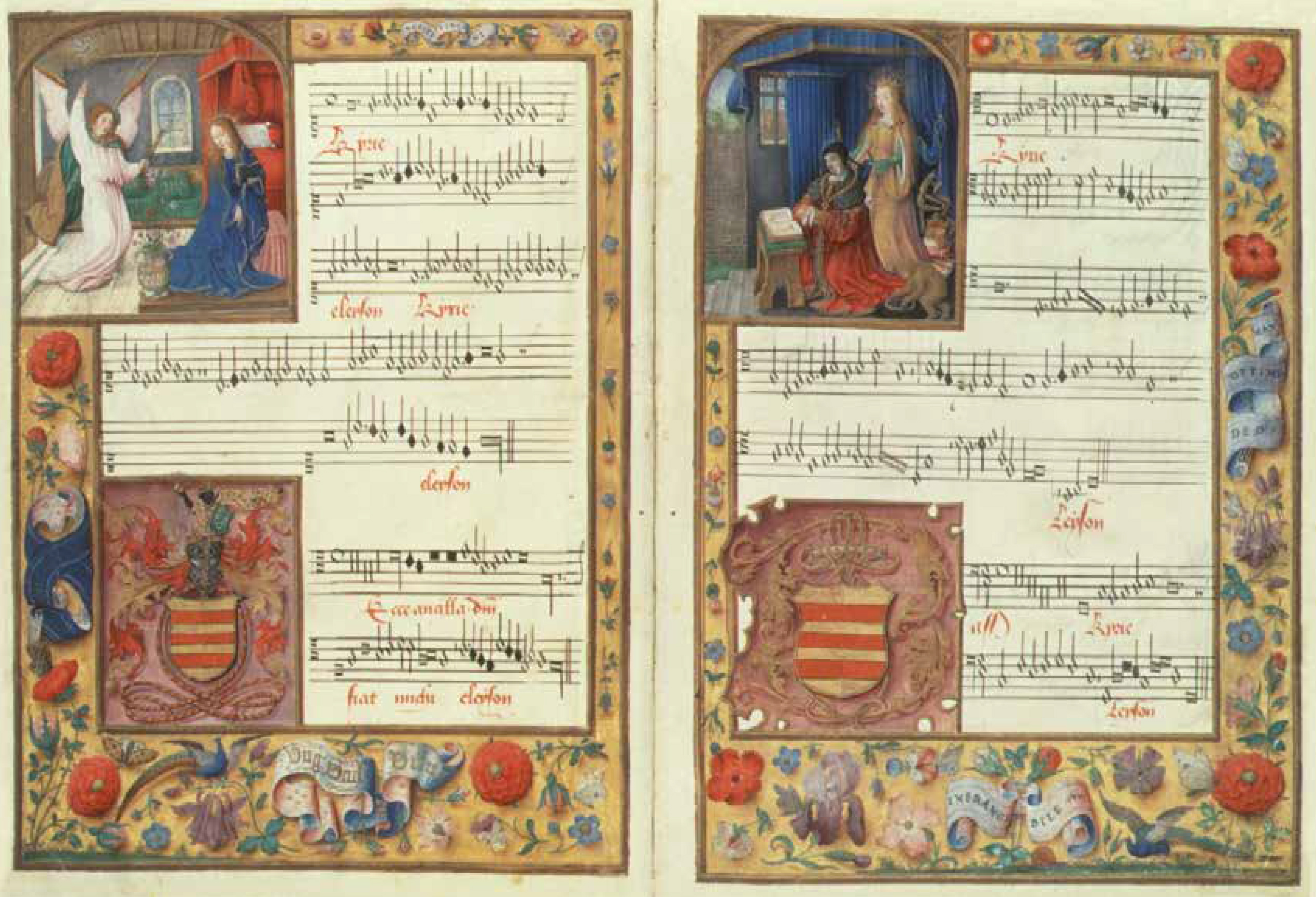

Manuscript page from the Chigi codex showing the Kyrie of Ockeghem’s Missa Ecce ancilla Domini. Cantus and tenor are on the left page, contratenor and bassus on right

The lectern's revolving reading desk acts as a resonating chamber, its surface giving instant feedback to the singers

Big books have charisma (the biggest surviving Tudor choirbook, in Gonville & Caius College Library, measures 72 x 96 cm when opened). The unignorable presence of such deluxe books and their props made choirbooks attractive to wealthy donors as pious donations or dynastic trophies, but it also attracted the hostility of Elizabethan reformers. For them, the only permissible lectern book was the Bible, while ‘curious singing’ (elaborate music) and its morally dubious practitioners belonged anywhere but centre-stage. It may be no coincidence that the only institution where lectern singing apparently persisted after 1559 was in Elizabeth I’s own chapel (hence the short-lived tradition of writing services ‘In medio chori’ by Chapel Royal composers like William Mundy).

Nowadays, singing from choirbooks is the preserve of a minuscule number of specialist early music ensembles, notably Cappella Pratensis. Academic researchers, meanwhile, have tended to focus less on the acoustic experience of singing from choirbooks than on the notational syntax of their contents (understandably: reading early notation helps reveal the hidden workings of medieval and Renaissance music). The busy timetables of cathedral and collegiate choirs, moreover, leave little time for experimental archaeology, while modern liturgies are not always best served by British repertoire from the choir lectern’s heyday – that is, melismatic Latin polyphony from the 1300s to the time of Henry VIII.

The composer Jean Ockeghem (d.1497) sings with the French chapelle du roi © PARIS, BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE, MS FR. 1537 (CHANTS ROYAUX SUR LA CONCEPTION, 1520S), F 58V

However, it is worth trying out a technology so perfectly adapted to ensemble singing that it lasted in some countries well into the 20th century. It was also a technology to which early publishers of Palestrina, Victoria and other Renaissance composers catered with lavish grand-folio choirbook editions. Choirbook format was, indeed, the norm for Masses, Magnificats and hymns (while motets and secular songs were usually printed in partbook format). Many of these books are now digitised. The Bavarian State Library’s prodigious digital collection includes, among many other choirbooks, Tomás Luis de Victoria’s annual cycle of hymns (printed 1581), or the two spectacular choirbooks containing Lassus’s seven penitential psalms (copied in the 1560s) where the composer is shown standing at a choirbook lectern with his colleagues from the Bavarian court Kapelle.

What does choirbook singing have to teach us? This question has underpinned a series of research projects undertaken during the ‘Experience of Worship’ project (2009-13) and in collaboration with professional ensembles the Binchois Consort and Ensemble Pro Victoria, and a church choir, St Wulfram, Grantham. The first revelation is that we don’t need large choirs to perform Renaissance polyphony. Most depictions of choirbook singing show smaller groups of singers than we would expect: the image of Jean Ockeghem singing with the French chapelle du roi shows nine singers, and we see the same number on the title page of Pierre Attaingnant’s Missarum Musicalium of 1532; the title-page of Nicolas Du Chemin’s mid-16th-century choirbooks shows six singers, four adults and two children, singing six-part polyphony, one to a part. One or two 16th-century choirbooks have enormous notes legible from a distance by large ensembles, but these are exceptional. Most choirbooks, printed or manuscript, comfortably accommodate around a dozen singers: a huddle rather than a chorus.

Ensemble Pro Victoria, directed by Toby Ward, sing Taverner's Quemadmodum from Newcastle University's choirbook lectern, New College, Oxford, autumn 2021. The revolving reading desk amplifies the sound, and also enables singers to toggle effortlessly from one book to another. The design of this lectern was based on that of Jean Ockeghem's, and its dimensions on the lectern in King's College, Cambridge © COURTESY RICHARD PAUL

Do fewer singers make a weaker, less cohesive sound? Not when they are singing at the lectern. Standing in one location, reading from a single book, has a powerful amplification effect with all voices focusing on one spot. The lectern’s revolving reading desk acts as a resonating chamber, while its surface gives instant feedback to the singers. We hear the other voice-parts in close proximity, helping intonation, blend, togetherness, communication and confidence. Body language is easy to read, and the ensemble breathes as one. The object acts as a focus for both eyes and ears.

These findings have been made during a series of experiments and collaborations. Singers have been encouraged to reflect upon their experiences: ‘Completely transforming! … we functioned more as a group without conscious eye-signals’ (2011); ‘led me to rely more on listening … helped me to blend better … also encouraged me to have better posture … helps to create a better sense of ensemble’ (2015). More recent feedback from both secular ensembles and church choirs bears out these earlier experiences: for Ensemble Pro Victoria, singing at the lectern enables the singer ‘to create a detailed, memorable and imagined mental picture of the work… greatly aiding memorisation of music, and a more intimate understanding of polyphonic textures’ (2022); for the choral scholars of St Wulfram, Grantham, ‘it felt much more intimate and connected than the way we sing together normally… being immersed in the sound was so powerful… singing closely together was really exciting, enjoyable and different – I was really inspired by it… I couldn’t wait to tell my musical family about it after’ (2023). In these experiments, we have used easy-to-read modern editions, in a combination of choirbook and score layout, rather than facsimiles of original sources: the emphasis has been on the spatial experience of singing at the lectern rather than on decoding the intricacies of early notation. Whatever their original format, dispensing with individual scores and singing polyphony such as Tallis’s O nata lux, Byrd’s Ave verum corpus, or a piece of plainsong from a single lectern copy, is a genuinely ear-opening experience.