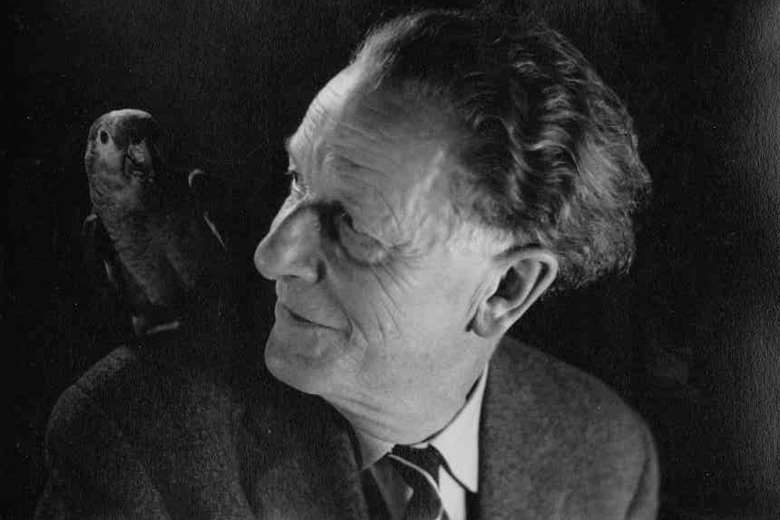

Frank Martin: spiritual mastery

David Wordsworth

Friday, November 8, 2024

Though often overshadowed by his contemporaries, Swiss composer Frank Martin crafted deeply spiritual and innovative choral works that reveal Baroque influences and profound personal faith

It is reasonable to assume that the names of Swiss composers do not exactly roll off the tongue of all but the most knowledgeable music lover – Ernst Bloch perhaps, born in Geneva to Jewish parents, but spending almost half his life in the US. Artur Honegger, an important figure, whose music remains a rarity in the concert hall. Then nearer our own time, the oboist, conductor and composer Heinz Holliger, and true choral aficionados may well be familiar with the work of Carl Rütti. If you Google the name Frank Martin it is an American professional boxer that appears first, not Frank Martin the Swiss-born composer (1890-1974), who died 50 years ago this year.

It was hearing a performance of Bach’s St Matthew Passion at the age of 12 that changed Martin’s life, and although at his parents’ insistence he was at first only able to study music alongside maths and physics at university, the composer later recalled that it was clear from that day what his life-long preoccupation would be. Bach did indeed remain the primary inspiration throughout Martin’s life, alongside his profound religious faith (he was the youngest of ten children born to a Calvinist priest) – the presence of J S Bach can certainly be heard in Martin’s sinewy counterpoint, rhythmic vitality and in the profound sincerity of every bar he wrote.

Those who appreciate the sacred works of Faure, Duruflé, Langlais, perhaps even Messiaen, will find Golgotha a natural progression

Remarkably it is only thanks to persistent persuasion from performers that we have Martin’s most famous choral work at all. The composer worked on his Mass for Double Choir between 1924 and 1926, but after the double bar had been written, he put the work away and did not seek a performance. The Mass remained hidden until the early 1960s, when the work was performed liturgically in Hamburg, and then waited until as late as 1970, just four years prior to the composer’s death, before the first concert performance in the Netherlands, where Martin had settled at the end of the war. Martin always insisted that the Mass was ‘a private matter between God and himself’ – indeed it is extraordinary to think that this most devout composer, who often spoke of how he tried to portray the spiritual in his music, was actively discouraged from writing any more sacred music at all until the mid-1940s.

Listening today, to such a personal statement, full of vigorous Baroque counterpoint and long flowing melodic lines that almost make bar lines redundant, one can only be grateful that perceptive people stepped in to save a 20th-century classic that might have disappeared for good. A recently revised edition published by Bärenreiter includes newly discovered specific instructions regarding the Mass, given by the composer at rehearsals he attended in late 1972 – yet another fascinating angle to this most mysterious and beautiful piece.

Martin’s other greatest work for a cappella choir is the 5 Songs of Ariel, written for the Netherlands Chamber Choir in 1950, clearly inspired by his only ‘grand opera’ The Tempest, yet another work that has unaccountably disappeared from the repertoire. These songs are rather more than shavings from a master’s workshop. Lasting around 13 minutes, they are a virtuoso workout for a choir, that show how far Martin had developed as a composer, in terms of harmonic daring, rhythm fluidity, as well as sheer élan and joy in showing off the range of colour and texture that it is possible to demand from a good choir. ‘Full Fathom Five’ might be seen as a close relative of the famous Vaughan Williams setting of the same text (curiously written only a year later), in its slowly moving blocks of sound, while the composers sparkling sense of humour can be heard in the buzzing of the bees, in ‘Where the bee sucks’.

Central to Martin’s output are his series of large-scale choral/orchestral works that span his most important creative period: In terra pax (1944), Golgotha – a Passion oratorio (1945-48), La Mystere de la Nativite (1957-59), Pseaumes de Gevene (1958), Pilate (1964), Requiem (1971-72) and the unfinished chamber cantata Et la vie l’emporta (‘And life prevailed’) (1974), which he was working on until a few weeks before his death. The shorter, but nonetheless engaging, Ode a la musique (1961), for baritone, mixed choir and an unusual ensemble of piano, brass and double bass, setting a text in praise of music by Guillaume de Machaut no less, is another piece that rewards investigation.

By far the most important are the two great wartime works that Martin laboured on for some five years. He called In terra pax a ‘short oratorio’ – it does last some 45 minutes and leaves a much deeper impression than the composer’s modest description might suggest. The work came about as the result of a request for a work that could be sung and broadcast at the end of the Second World War. Though Martin wrote that he had no illusions about the future of the kind of peace that would come, what the piece vividly portrays is a feeling of relief, a joyful hope for the future, and above all a mystic prophecy of ‘a new heaven and a new earth’, that must have been in the minds of many after years of turmoil. Central to In terra pax is the very simple setting of The Lord’s Prayer, sung by unison voices with organ – a tiny oasis of calm that can be performed separately in English, French or German with keyboard accompaniment.

Golgotha,described by Michael De Sapio as ‘a Passion for the 20th century’ (it can be sung in French or German), is on a larger scale, of some 90 minutes. Initially inspired by a collection of etchings by Rembrandt that portray different visions of calvary and the crucifixion, Golgotha is an emotional, deeply felt meditation that takes us from despair, the betrayal of Christ, the scenes of his trial and crucifixion, to an impassioned hope, setting the words of St Augustine – ‘True and certain light/Unique source of light/Essential and sovereign light’. Those who appreciate the sacred works of Fauré, Duruflé, Langlais, perhaps even Messiaen, will find Golgotha a natural progression, the Pelléas-like vocal lines, combining with Georgian chant and the composer’s reverence for Bach, together creating a completely individual musical language that is on the one hand deeply felt and intense, and on the other hugely striking and uplifting.

Martin often spoke of his wish to write a requiem – it was only towards the end of his life that he felt able to fulfil that wish. It is scored for four soloists, and an orchestra that includes an organ and a harpsichord that merge in and out the texture rather than take any prominent role. The Requiem can be heard not only as a characteristic Martin-like journey from darkness to ever-lasting light but also as an acutely personal journey through life, that he must have known must soon come to an end. The composer spoke of his intention to make the text as clear as possible, as a result, the contrapuntal element, so important in Martin’s music, appears to have been stripped back. Although not making an easy listen, the Requiem is perhaps Martin’s most austerely beautiful work and is acclaimed by some as his masterpiece. Martin wrote that he hoped ‘... it might bring some people the same feeling of trust and peace that moved my soul while I was working on it’. Rarely heard since its premiere, the Requiem more than warrants regular revival.

While researching for this article, I came across a piece that I had not heard before, a tiny gem that exists for both unaccompanied female and male voices, one of many shorter pieces that space prevents me discussing. Petite église (‘Little church’) is a distillation of the art of Frank Martin in a few minutes. A perfectly crafted miniature, direct, without any wasted notes, touching in its apparent simplicity and yet sophisticated in its thought, so typical of this underrated 20th-century master. The final lines of de Machaut’s text that Martin set in Ode à la musique are a description of Orpheus but are a fitting epitaph for Frank Martin himself: ‘…to hear and listen to him, so we must certainly believe that these are miracles worked by Music. This is the truth for sure.’

David Wordsworth is a freelance choral conductor and workshop leader, and author of Giving Voice to My Music – interviews with choral composers (Kahn and Averill, 2021)