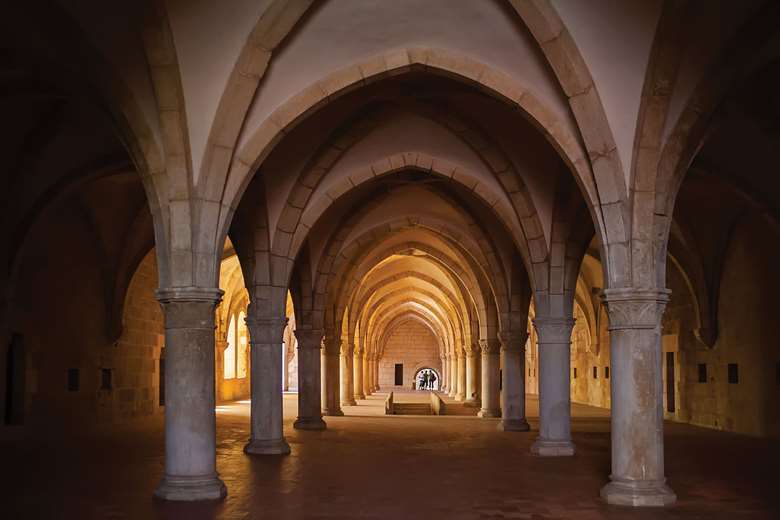

The choral sound of contemporary Portugal

David Wordsworth

Friday, February 21, 2025

David Wordsworth introduces his series looking into the choral traditions of countries we know little about, beginning with Portugal

Though many of the composers belonging to the golden age of Portuguese polyphony might be less celebrated than their Spanish contemporaries, the names of Manuel Cardoso, Duarte Lobo, Filipe de Magalhães and others have lived on, despite many manuscripts of the time being destroyed by the cataclysmic earthquake and tsunami of 1755 that destroyed Lisbon and much of the Algarve. Few native composers from the classical and romantic periods are well known outside of Portugal, and indeed as we reach the 20th and 21st century, the period that this article will concentrate on, the wide repertoire of choral music has not travelled extensively. As several of the composers have pointed out to me, although there are a good many choirs in Portugal, there is a relatively small market for their work (especially texts that are set in their native language) and publication and distribution is not easy.

Significant figures from the 20th century include Cláudio Carneyro (1895-1963), who spent a good deal of time in Paris, studying with Widor and Dukas, and so it is hardly surprising that his work has a rather sophisticated French feeling, as well as retaining a distinctive Portuguese flavour. Of particular importance are Carneyro’s many works for unaccompanied choir, both sacred and secular – perhaps his best-known works are those for upper-voice choir, such as Ave Maria (1935) and 4 Romances Populares (1942).

Frederico de Freitas (1902-80) played a vital role in 20th-century music in Portugal as a composer, conductor (he founded the Lisbon Choral Society in 1940) and teacher. His music is often of a nationalist flavour, while also acknowledging the neo-classical and polytonal styles of the 1920s and ’30s.

His wartime Missa Solene (1940) is particularly admired – this was followed by two other Masses, Missa Regina Mundi (1954) Missa in Honora de Sao Cristovao (1973) and the very fine Stabat Mater (1971) for unaccompanied choir.

Fernando Lopes-Graça (1906-94), whose music has been little heard outside of Portugal, was a hugely important figure, whose political dissidence meant his early or indeed later career did not proceed as he had hoped. Lopes-Graça was imprisoned more than once for his political stance and was certainly prevented from taking high-level academic positions. Although studying in France with Koechlin, it was once again the music of his native Portugal that drove most of his musical inspiration. His musical voice has been compared to composers such as Bartók, Prokofiev and Ginastera. Like several of his colleagues he was also a choral conductor, making many transcriptions and arrangements for amateur and student choirs. Lopes-Graça’s Cancoes Regionais Portuguesas is thought of as one of the most important works of its kind, taking the ideas of Bartók, Kodály and Vaughan Willams, and preserving, or even rescuing, a truly national music. Paul Hillier and Coro Casa da Música made a fine recording of these striking pieces for the Naxos label, which, also for the Christmas Cantata, is worth seeking out. On a rather different scale is the Requiem – For the Victims of Fascism in Portugal (1979), showing perhaps a less accessible side to the composers’ personality, the visceral anger at times even recalling the experiments of the Polish avant-garde.

The two major Portuguese composers of the mid-late 20th century were Joly Braga Santos (1924-88) and Jorge Peixinho (1940-95), both renowned as mentors/teachers and conductors. The early work of Braga Santos received encouragement from Vaughan Williams, attempting as he did to utilise the folk tradition of his homeland in his symphonic works, writing no fewer than six symphonies (the last, No 6, being a choral symphony). His later music took on a more chromatic flavour, but as his only major choral work, the large-scale Requiem (1964) shows, after a curiously fragmented introduction, that Braga Santos did not move far away from tradition and the sounds of chant and renaissance polyphony are never far away. The Requiem is an impressive piece that warrants further investigation. Its large forces, including no fewer than six soloists, has perhaps hampered exposure. Peixinho came under the influence of some of the major figures of the European avant-garde such as Nono, Boulez and Stockhausen an wrote little choral music, following a much more radical path.

The large output of Fernando C Lapa (b1950) who is based in Porto (also known as Oporto), Portugal’s second city, includes music for film, theatre, television, as well as every conceivable genre for the concert hall, often exploiting unusual instrumental combinations. As a choral conductor he was the founder of the celebrated Minho University Academic Choir.

A great deal of Lapa’s work takes texts and traditions of his homeland as its starting point, but there are a large number of works that set more conventional texts, Salmo 50 (2016), Puer Natus Est Nobis (2004), Tenebrae (2001), as well as arrangements of tunes that might come as a surprise from a Portuguese composer – Jingle Bells, The Last Rose and Amazing Grace. His catalogue also includes many works for flexible school ensembles or educational purposes. Missa da galina (2018) is for voices, piano and school ensemble; his Magnificat (2013) is for children’s choir and organ.

Manuel Pedro Ferreira (b1959) is a distinguished musicologist with a particular interest in medieval music, an influence that is apparent in his own choral music, such as Salve Regina (2022), Sanctus (2019) Agnus Dei (2019), while his earlier setting of W B Yeats’ Mother of God (1998), shows in some ways a more radical approach, while still clearly acknowledging the past.

Eurico Carrapatoso (1962) came to composition rather late, being in his mid-twenties before his first pieces came to public attention. Since then, he has certainly made up for lost time and has amassed a large output of music for mixed, male, female and children’s choirs that have made him by far the most frequently performed Portuguese composer of his generation, both at home and abroad, appreciated by both amateur and professional choirs alike. Many of his works quite naturally set texts in his native language but there are also a significant number of works that set Latin and even English texts – Magnificat (1998), Stabat Mater (2006), Pangue Lingua (2020), the remarkable Deo do Ceo for massed voices and no fewer than six organs, as well as shorter anthems, motets and Psalm settings.

Carrapatoso’s stylistic fluidity takes account of both the sacred and secular traditions of Portuguese music, but also the capabilities of the singers he is writing for, always naturally and gratefully written.

Alfredo Teixeira (b1965) teaches at the Catholic University in Portugal and is another composer whose music celebrates the Catholic liturgy and Portuguese poetry, paying homage to the past, while looking forward to the future.

His work, primarily of a reflective character – Canticle of Ecstasy (2022), inspired by texts by Hildegard of Bingen, is a particularly striking example of Teixeira’s art, as is Pai, morte vem (2022) in which an alto saxophone comments on the rich choral textures and the brief Alleluia (2020). Those attracted to the austere beauty of much of the music of the early 21st century would surely be attracted to this very beautiful sound world.

Luís Tinoco (1969) has strong connections with the UK, having studied at the Royal Academy of Music and York University. Most of his music is for chamber or orchestral forces but there are at least two short effective works for unaccompanied voices, Descubro a Voz (2012) and Ink Dance (2012), as well as a more extended ‘dramatic scena’ for children’s voices and orchestra Journeys of a Solitary Dreamer (2012).

A brief survey like this can barely touch on the rich heritage of choral music in Portugal that is worthy of investigation but I hope it can pave the way for conductors to discover for themselves music that certainly deserves a wider exposure than has been the case.

David Wordsworth is a freelance choral conductor and workshop leader, and author of Giving Voice to My Music – interviews with choral composers (Kahn and Averill, 2021